Introduction

This post focuses on three school districts’ efforts to authentically engage families and communities in improving student outcomes, and our analysis of these efforts.

Since the onset of COVID, school districts have grappled with extraordinary challenges, significantly impeding their operational capacity to meet student needs without compromising educators’ mental and physical health. To address capacity issues, many districts have turned to their local families and community organizations for support. Family engagement research has shown that when families and schools work together, children are more likely to have better attendance, succeed in school, graduate on time, and stay on their path to college and/or career (Weiss et al., 2018; Henderson & Mapp, 2002). This post focuses on three school districts’ efforts to authentically engage families and communities in improving student outcomes, and our analysis of these efforts. First, we provide our definition of family and community collaboration and theoretical framing, then a description of how we identified sites and the data we collected, and finally a brief presentation of findings.

Definition of Family and Community Collaboration

In defining authentic family and community collaboration we reviewed a mix of theoretical frameworks, academic articles, community-based organizational models, national association frameworks, and technology-based tools. Ultimately, we adopted Grant & Ray’s (2019) definition of family and community collaboration as “a mutually collaborative working relationship with the family [and community] that serves the best interest of the student, in either the school or home setting, for the purpose of increasing student achievement”. But three theoretical frameworks strongly influenced our study and served as a critical reference to our approach:

- Karen Mapp’s Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships: The framework’s four Cs (capabilities, connections, cognition, and confidence) describe a pathway for building educators’ and families’ capacity in improving student achievement. This framework pushed us to ask what policies and procedures school districts use to weave collaboration into everyday practice.

- Ann Ishimaru’s Family Leadership Design Collaborative: The following four principles guide this framework to reduce educational inequities and focus on placing power between communities and schools. This framework pushed us to ask how school districts disrupt traditional, hierarchical engagement to collaborate with various racial, ethnic, class, or immigrant groups.

- Joyce Epstein’s School-Family-Community Partnership Model: This framework emphasizes the idea of interdependence between school and families through six types of involvement: parenting, communicating, volunteering, learning at-home, decision-making, and collaborating with the community. This framework pushed us to ask what types of activities school districts promote in involving families and community groups.

Our five focus areas of family and community collaboration call for:

1.Trust between the district, families, and communities.

2. Integrated family and community values are embedded throughout district policies and mindsets.

3. Authentic collaboration in planning and decision-making.

4. Sustainable structures and funding to maintain efforts.

5. Equity in all engagement efforts.

From these frameworks we developed five focus areas of family and community collaboration. All three frameworks raise the need for trust between school districts, families, and communities to maintain strong partnerships and create safe spaces for all voices to be heard on critical issues. They also highlight the strength of integrated values, as each group provides important insight and resources to help students thrive although these frameworks model collaboration slightly differently. Additionally, all three frameworks emphasize authentic collaboration among districts, families, and community members in planning and decision making. Both the Dual Capacity-Building and Family Leadership Design Collaborative focus on sustainable structures and funding in education that support effective collaboration, such as districts having collaboration goals and policies specifically for family engagement. Lastly, both the Family Leadership Design Collaborative and School-Family-Community Partnership models focus on equity or how districts must specifically engage to bring marginalized families into the work.

Methods

Our study employs a multiple-case-study methodology to highlight three exemplary school districts that vary in size, geography, and population served, each distinguished for their family and community collaboration initiatives.

To investigate the innovative, creative, or exemplary practices districts used to maintain authentic family and community collaboration post-COVID, our study employs a multiple-case-study methodology to highlight three exemplary school districts that vary in size, geography, and population served, each distinguished for their family and community collaboration initiatives. Our focus is on identifying best practices and evidence-based strategies utilized by these districts to foster authentic engagement with their communities. The process for identifying case studies districts involved multiple steps:

- Nominations: We initiated a national call for recommendations via an online form distributed widely amongst our social networks as well of those of identified experts and national researchers in family and community collaboration. In total we received 89 nominations during a 1-month open window.

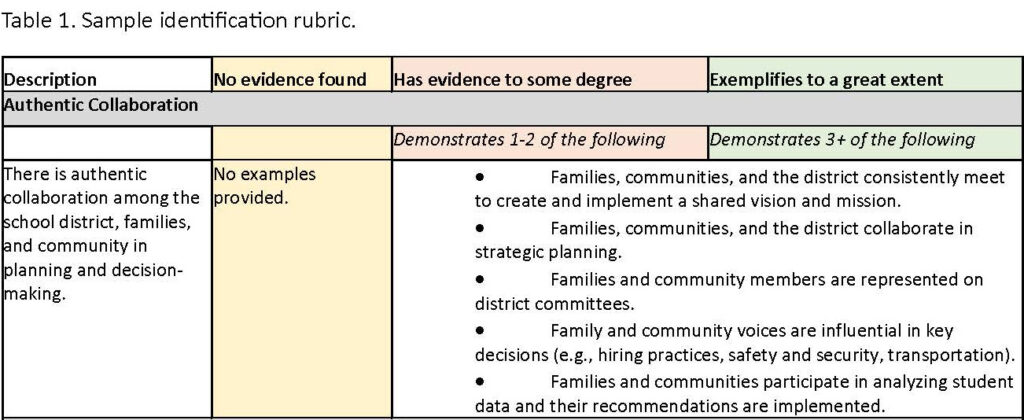

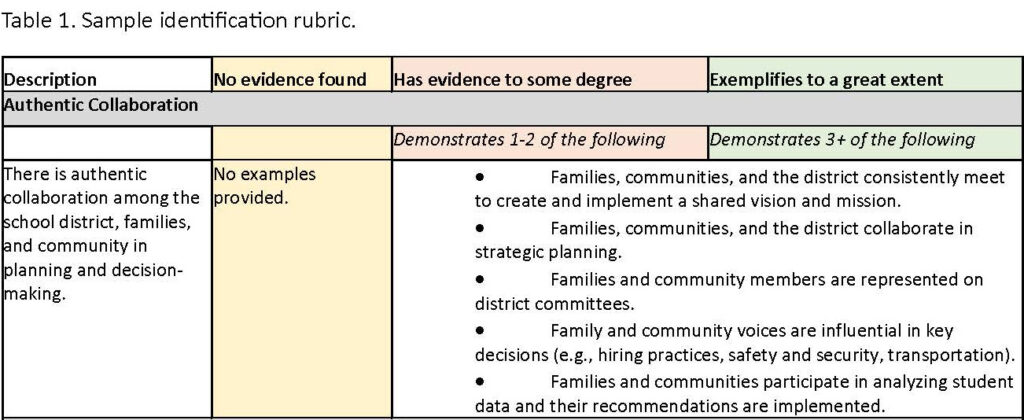

- Identification rubrics: For each nomination we documented district characteristics (e.g., geographic region, locale, student demographics). Additionally, we completed a screening rubric that used aspects of each of our three critical frameworks. For example, for each focus area we identified unique contributions and identified examples that exemplified these aspects (see Table 1.)

- Screening interviews: After completing the rubric, we identified 13 districts to participate in brief 45-minute follow up screening interviews. These interviews helped us determine district interest and gather additional information regarding their family and community collaboration practices. The districts were evaluated in terms of their collaboration practices with marginalized groups (e.g., multilingual families, youth) and how feasible it would be to conduct a site visit within our timeframe.

- Final selection: Ultimately, we chose three districts that aligned well with one or more of our five focus areas and who were successful at accelerating, scaling, and sustaining community engagement practices and strategies. Final sites were chosen based on district diversity in representing varying racial and ethnic groups.

School districts selected as case study sites actively participated in a series of pre-visit planning interview, a three-day in-person site visit, member-checks to validate findings, and a virtual meeting with all sites to review findings and help map strategies could inform others. During our onsite visits we conducted the following semi-structured interviews and data collection activities:

- District staff interviews: We interviewed district office staff responsible for family and community collaboration, including engagement officers, superintendents, communication offices, and equity offices.

- Local organization interviews: We spoke with local community-based organizations working closely with the district. Student interviews: We engaged with students ages 12-17 who have engaged in family and community collaboration through committee work or district-level events.

- Community member focus groups: We held focus groups with community members, including parents, teachers, principals, and community organization staff, who have been involved in family and community collaboration.

- Event observations: We observed family and community collaboration events, tours of local areas and schools, and resource centers.

- Document collection and review: We collected and reviewed internal and external district documents, such as district handbooks and policies, websites, and/or social media posting of family events.

We conducted descriptive coding of the focus groups and interview transcripts using Nvivo. Descriptive coding emphasized the strategies, supports, and resources district leaders needed to overcome challenges post-COVID.

Analyzing the data involved reorienting to the theoretical frameworks to continually refine how districts shifted structures and mindsets, disrupted traditional power structures for equity, and engaged in various types of activities to increase collaboration. We conducted descriptive coding of the focus groups and interview transcripts using Nvivo. Descriptive coding emphasized the strategies, supports, and resources district leaders needed to overcome challenges post-COVID. Each site was analyzed independently to understand how they accomplished these goals and then we engaged in cross-case analysis to discern similarities and differences in improving collaboration.

Findings

To bring in community members, districts utilized decision-making bodies such as advisory councils and task forces, leveraging the strengths of families and local organizations.

All identified districts prioritized creating collaboration-specific staff roles and responsibilities and involving community members in roles to ensure that teachers did not do this work alone. These districts also sought resources from external funders and community organizations to fill in gaps and build bridges to support services. Importantly, each district acknowledged families’ needs (e.g., clothing, laundry, food), and created “one stop shops” so that families could easily overcome barriers without additional, complex, and bureaucratic hurdles. The experience of living through a pandemic and the associated disruption and trauma young people experienced during that time dramatically increased the need for mental health services. As such, all the resource centers had specialized staff such as social workers or counselors to meet mental health needs. To bring in community members, districts utilized decision-making bodies such as advisory councils and task forces, leveraging the strengths of families and local organizations. These formalized channels made it easier to collaborate with a representative selection of community members.

Conclusions and implications

Future research is necessary to assess whether these efforts effectively support educators’ operational capacity, mental and physical health, and structures needed for sustainability.

These case studies demonstrate how districts can ease the burdens on educators and incorporate diverse perspectives by adding new positions, programs, and community bridges that emphasize family and community collaboration. While these examples provide hope in expanding more collaborative systems that engage diverse perspectives, future research is necessary to assess whether these efforts effectively support educators’ operational capacity, mental and physical health, and structures needed for sustainability. If you are interested in more detail on family and community collaboration strategies districts used to overcome these challenges, please see our recent journal article “Roadblocks to Effective District, Family, and Community Collaboration: A Phenomenology Study of Potential Challenges and Solutions” in the journal of Leadership and Policy in Schools.

Click on image to view complete sample rubric.

Sharing is caring!