By: Rachel Hatch (FHI 360) and Carolyn Alesbury (Save the Children)

Since the launch of the Disability Task Team under the Education Equity Research Initiative in 2017, a significant theme of the group’s work has been on researching effective and efficient screening tools for children with disabilities. Task Team members have presented on experiences using specific tools in different contexts, conducted analysis of cross-country approaches and consolidated a mapping of different tools available. These timely efforts coincided with a period in which donors have been requiring more data disaggregation by disability, and establishing their own guidelines for using screening tools in education projects.

As we wrap up the Equity Initiative, we can continue to use the Disability Task Team’s many contributions as a road map for a sustained commitment to strengthening research on screening tools for children with disabilities. Below, we have brought together the many strands of this work to present key guidance for implementers on how disability screening can be responsibly integrated into education programming.

1) Taking key ethical considerations into account

Some projects use disability screening to inform the specific support provided to specific children – for example, referral systems to ensure students who need glasses or speech therapy or accommodations from their teacher get the support that they need. Other projects use disability screening to enable them to disaggregate monitoring and evaluation data based on the binary categories of “children with disabilities” and “children without disabilities”. These are two very different reasons to conduct disability screening, with very different results for the children involved.

Ethical research principles call for maximizing benefits and minimizing risks for those involved – disability screening brings the risk of exposing a child to potential stigma and discrimination, and it is important that those risks be minimized as much as possible, while also maximizing the individual benefit children will receive from allowing themselves to be screened. To that end, if a project is motivated primarily by being able to disaggregate data by disability, it is strongly recommended that (1) referral pathways and services are established to ensure that the potential risks to a child are outweighed by benefits and (2) informed consent should ensure that participants (and in the case of young children, their parents) are aware of the benefits and risks of the screening, and offer them the opportunity to opt out at any time.

2) Individual screening: Selecting an approach

Approaches to disability screening range from targeted individual medical assessment of a child, to administration of a brief questionnaire to parents without the child even being present. In higher resource areas, disability screening takes place at multiple stages of a child’s life, including robust referral pathways and the involvement of specialists and multi-disciplinary teams. In areas where such systems are not in place, school staff may take on more of the responsibility of conducting screenings and referrals. Although evidence has found that teachers can conduct basic screenings in the absence of other options, recent evidence has found that it would be more effective to support the local health infrastructure to conduct the screenings, rather than adding it to teachers’ workloads. Ultimately, the most appropriate tool(s) to be used will depend on three key factors:

- Who is going to be administering the tool? (e.g., teachers, Ministry of Health staff, project staff)

- To whom is the tool being administered? (e.g., directly to children, to parents about children, to teachers about children)

- What types of disability will be screened? (e.g., vision, hearing, motor, cognitive, learning, behavioral, communication, socio-emotional, self-care, etc.)

Depending on the answers to these questions, implementers may choose to use one or more of the low cost tools that are available. Some of the tools have been vetted more widely than others and some are more readily adaptable to new contexts – the mapping highlights some of these nuances to help practitioners choose the tool most appropriate for their initiative. Regardless of the tool, it is important to ensure that those using it have received the training and guided practice necessary to apply it effectively and respectfully.

3) Prevalence screening: Using the Washington Group and UNICEF questionnaires

Any conversation about screening approaches invariably highlights the Washington Group and UNICEF questionnaires, which have been widely used and validated, are commonly included in censuses and the UNICEF multiple indicator cluster surveys (MICS), and are recommended for use by both DFID and USAID. The questionnaires are based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) domains of functioning, and ask about the extent to which individuals experience difficulty in each of the functional areas. It is important to note that these tools do not provide formal diagnoses, but rather describes the impact of possible conditions on functional abilities. Students found to have functional difficulties in any area can be referred to specialists for further assessment and diagnoses – this also ensures more efficient use of resources when there are not sufficient specialists available to examine all children.

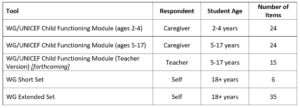

Depending on the age of the student, and the identity of the respondent, one of the five questionnaires would be appropriate:

4) Putting it all into practice

While further referral is necessary for formal diagnoses, the information gathered through school-based disability screening is still highly useful from a classroom, project and education system perspective. Clarifying which children face functional challenges in different domains can, and should, guide teachers’ pedagogical approaches to better meet their needs. Children’s screening information can be used to inform individual education plans, as well as lesson planning more generally. At the project level, screening information should be used to disaggregate data and identify where gaps exist in access and participation, and for which groups of children. At the education system level, the number of students screening positive for functional challenges can help inform the allocation of resources, and ongoing teacher professional development.

The Disability Task Team’s research contributions in this area support global efforts towards systematic, intentional and ethical disability screening processes. Over the past three years, the Equity Initiative provided a vital learning forum and collaborative network to convene and subsequently mobilize disability experts at the intersection of research, policy and practice. The synergies ignited critical conversations on where the research gaps exist and how to work on filling them. Moving forward, we continue to use the lessons learned to guide our work and remain committed to advancing best practices on disability screening worldwide.

This post is cross-published on the Education Equity Research Initiative’s blog.

Photo caption: Teacher administering a vision test in a rural African school (Kenya)

Photo credit: Community Eye Health/CC BY-NC 2.0 license