This blog post is catalogued as a resource on USAID’s EducationLinks website.

Educators, psychologists and even economists have identified the critical importance of social and emotional learning (SEL) in education. Research shows that SEL can have a positive impact on school climate and promote a host of academic, social and emotional benefits for students. SEL is critical to creating a learning environment where all students can reach their full potential as these competencies provide a foundation for safe and positive learning, and enhance students’ ability to succeed in school, careers and life. SEL is even more relevant during COVID-19 as the transition to full-time distance learning in the wake of the pandemic has brought changes and multiple challenges to educators, parents and students.

Therefore, the challenge for education systems is no longer if we incorporate SEL but rather how, especially in these critical times. In this post, we reflect on critical learnings from a formative study we led that examined successes and challenges of a pilot program that integrated SEL into a pre-service teaching practicum course in Guatemala. Our learnings seek to provide educators, practitioners and policymakers with insights to understand the “how” for integrating SEL into pre-service teacher education.

The pre-service SEL practicum-based pilot program

The curriculum adopts the CASEL framework and the corresponding SEL competencies: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, responsible decision-making and relationship skills. Using this framework, we designed the curriculum with our program team based on three key pillars: building teachers’ own SEL competencies and wellbeing; creating safe, inclusive and supportive learning environments for students; and implementing low intensity and targeted SEL activities for children and adolescents. Through this strategy, teachers explore how to integrate SEL in mathematics instruction through three main approaches: general teaching practices, free-standing short SEL activities, and a combination of SEL and mathematics content focusing on activities that promote cooperative learning and growth mindset.

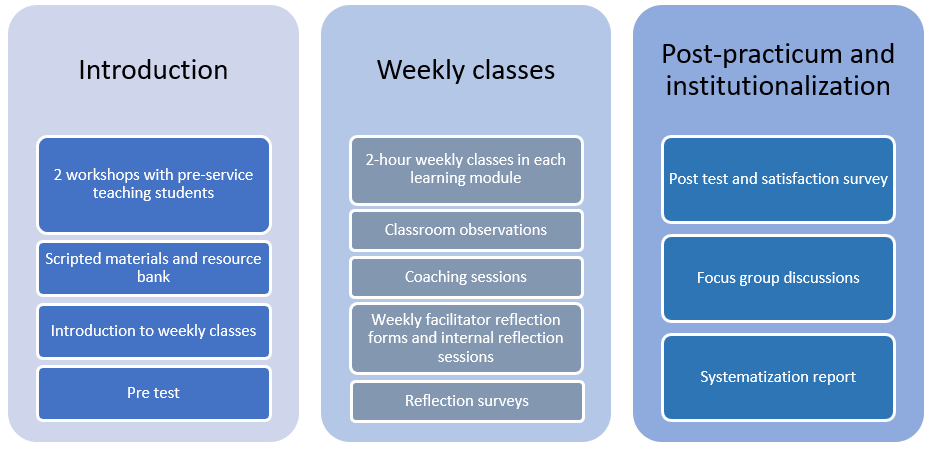

To deliver this curriculum our team designed an implementation strategy that consisted of integrating SEL into a 16-week practicum course. This strategy included starting with two two-day workshops (32 hours of instruction), and then continuing with the practicum during one academic semester, which consisted of facilitating two-hour weekly classes. Through the practicum, teachers had weekly in-classroom practice in secondary schools where they had the opportunity to teach to students.

During this time, our team conducted classroom observations and guided the teachers through one or two coaching sessions. We also provided background materials on SEL and teacher-scripted guides to guide their instruction and self-reflection on integrating SEL.

Study methods

To monitor and assess results, we incorporated quantitative and qualitative methods, including structured surveys and self-reflection forms directed at capturing teachers’ comprehension of concepts, satisfaction with the different elements of the program and self-reported changes. In addition, to get a more in-depth understanding of participants’ perceptions and experience in the pilot, we conducted three focus groups discussions with teachers. We incorporated lessons from the different assessment methods into a systematization report. Figure 1 below provides a detailed list of assessment methods.

What have we learned from the pilot program?

We can integrate SEL into previously established pre-service education curriculum structures. By successfully infusing the SEL curriculum into the practicum course, this pilot demonstrated that integration of SEL into a pre-established curriculum is feasible.

We recognize, however, that integrating SEL into pre-service teacher education programs requires infusing a focus on the social and emotional dimensions of teaching and learning throughout the pre-service preparation process and not only into a single course. During the focus group discussions, teachers reported challenges retaining certain SEL concepts after the pilot and mentioned the need to have more time to continue practicing specific competencies to be able to fully incorporate it into their pedagogy. We recommend that to maintain consistency and alignment in approaches across the pre-service program, there is a need for a common language across the curriculum. While this may not be always feasible, programs should consider continuous professional development for faculty and staff through professional learning communities (PLCs) on SEL and through coaching and mentoring opportunities.

SEL integration into pre-service education may require a shift from teacher-directed models of instruction to student-centered methods. Weekly reflections and focus groups revealed a misalignment between active and student-centered methods incorporated in the SEL practicum class and teacher-directed models adopted by other university coursework. This shaped teachers’ learning prior to the practicum. During focus group discussions, teachers mentioned that mathematics instruction in Guatemala most often follows a teacher-centered process of learning. This is problematic because to properly implement and integrate SEL into instruction, a teacher must be comfortable with abandoning the traditional, teacher-directed model of instruction.

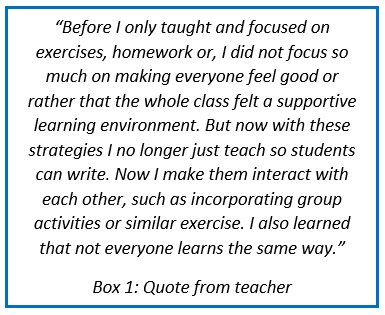

Acknowledging these challenges, our program team strengthened its original design and placed further emphasis on promoting experiences of teachers as students learning within a learner-centered approach. We did this to further develop their capabilities to use these approaches in their classrooms as practicum teachers. After the formative study, we found that teachers indeed showed a change in their pedagogical didactics away from lecture-driven classes as illustrated in box 1. During classroom time, teachers mentioned including socially-oriented learning activities that place emphasis on collaboration and peer interactions, and self-reflection exercises.

Acknowledging these challenges, our program team strengthened its original design and placed further emphasis on promoting experiences of teachers as students learning within a learner-centered approach. We did this to further develop their capabilities to use these approaches in their classrooms as practicum teachers. After the formative study, we found that teachers indeed showed a change in their pedagogical didactics away from lecture-driven classes as illustrated in box 1. During classroom time, teachers mentioned including socially-oriented learning activities that place emphasis on collaboration and peer interactions, and self-reflection exercises.

Developing pre-service teachers’ own social emotional competencies facilitates SEL inclusion in the classroom. We found that 85% of teachers reported that they improved or significantly improved their own social and emotional competencies and wellbeing as a result of their participation in the pilot. While we cannot draw a direct correlation, we believe this might have been translated into 82% of teachers modeling social and emotional competencies and promoting SEL activities when observed in their practicum classrooms. By understanding their own social and emotional competencies, teachers were more likely to model and foster these skills in their practicum with secondary school students.

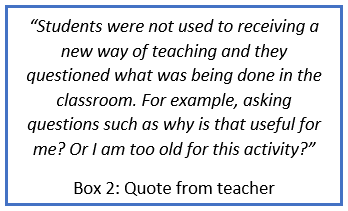

We need a whole-school approach for effective implementation of SEL. During focus group discussions, a few teachers reported experiencing resistance from principals and other teachers in schools where they conducted their practicum, who questioned or expressed not fully supporting the implementation of SEL. As illustrated in box 2, teachers frequently mentioned that even secondary school students doubted the utility of SEL activities to their own learning experience.

We need a whole-school approach for effective implementation of SEL. During focus group discussions, a few teachers reported experiencing resistance from principals and other teachers in schools where they conducted their practicum, who questioned or expressed not fully supporting the implementation of SEL. As illustrated in box 2, teachers frequently mentioned that even secondary school students doubted the utility of SEL activities to their own learning experience.

This is evidence of the need for promoting SEL as a schoolwide initiative where all adults, children and adolescents in the school (at minimum) understand the importance of SEL, and teachers and school staff can promote it in their interactions with students. We recommend that pre-service education programs establish stronger partnerships with secondary schools in which teachers conduct their practicum to create opportunities for school staff and leadership to learn about SEL. Data from the focus group discussions showed that generating buy-in and commitment on SEL is crucial to ensure quality of implementation and sustainability.

Ongoing contextualization of SEL approaches to school and classroom realities is key. As part of our adaptive program approach, we reflected with teachers on realities within which they conducted the practicum on an ongoing basis and experimented with different strategies that seeks to promote students’ SEL within the limitations of these realities. These reflections revealed several factors at the school and classroom level that impacted teachers’ ability to effectively implement SEL approaches in the classroom. These factors included secondary school students’ limited prior exposure to SEL and to participatory teaching methods; limited class time for SEL combined with loss of instructional time due to multiple transitions; as well as school infrastructure limitations such as over-crowded classrooms, limited spaces and resources.

Our program adapted its approach to overcome these challenges through further contextualization of SEL activities to adjust to the realities of schools where the teachers were practicing. We did this, for example, by infusing SEL into the teaching of mathematics to maximize the use of available instructional time, and by preparing SEL activities that only required use of available local materials and resources. We recommend that future programs recognize and focus on the ongoing contextualization of SEL interventions to their realities in the classroom.

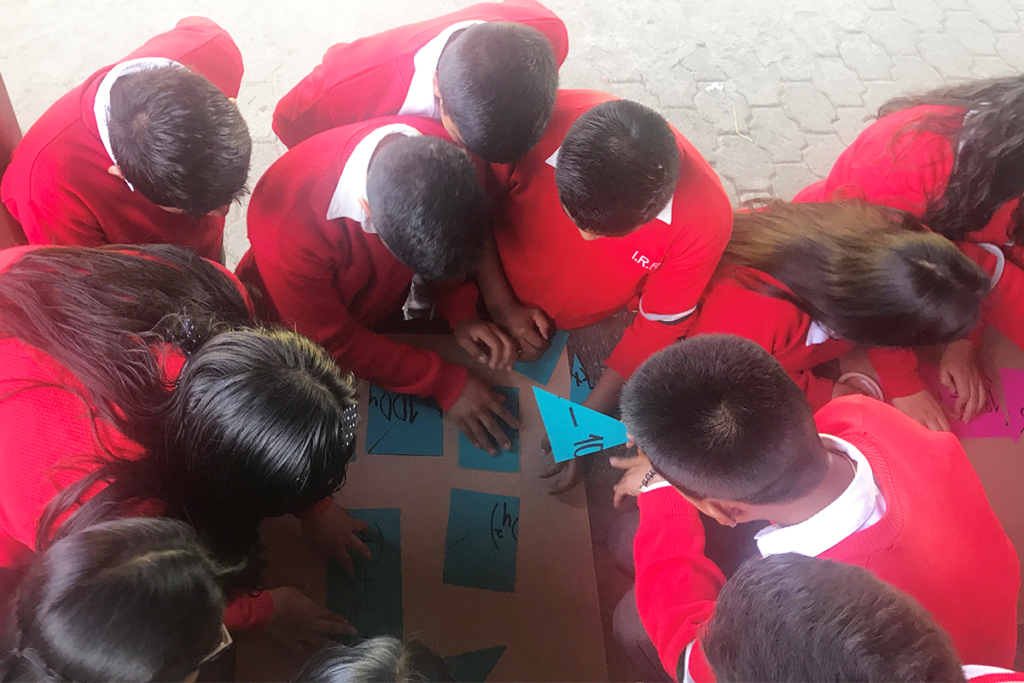

Photo caption: Students working in a game-based collaborative activity during a coaching classroom observation

Photo credit: Fernanda Soares/FHI 360