Introduction

This post presents evidence collected at the end of the project’s fourth year about the effectiveness of the different non-formal education modalities Passerelles implemented and examines the factors shaping transitions from non-formal to formal education. Our study found that nearly one-third of participants in the project’s non-formal modalities successfully transitioned to formal school. While seemingly modest, this change represents a significant improvement in extending educational opportunities to previously excluded children and youth. This research provides a valuable model for how to design similar program evaluations.

The Passerelles approach: What do “relevant” and “responsive” non-formal models look like?

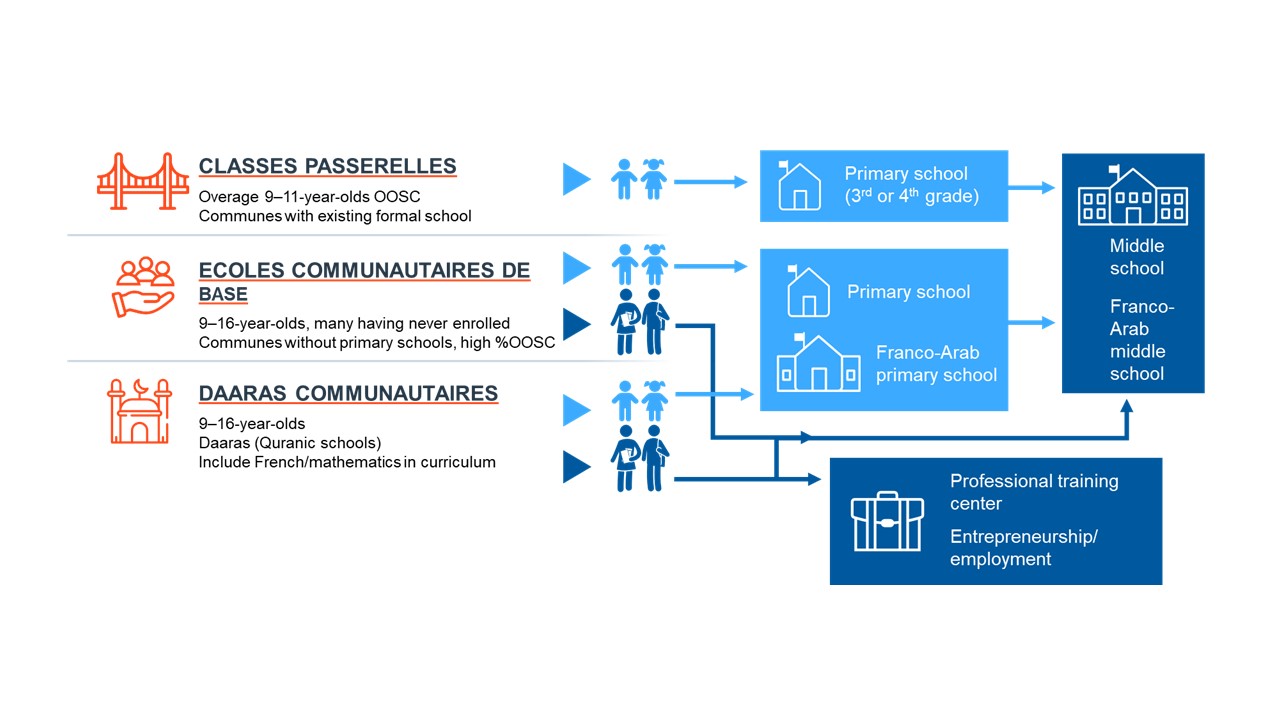

- Classes Passerelles (CP), meaning “gateway classes” in French, consisted of nine-month accelerated education programs targeting children ages 9-11 years old who had dropped out or were older than the age limit for the grade in which they should enroll. Originally developed by UNICEF in Senegal, Passerelles worked to establish new Classes Passerelles in communities with existing primary schools and where children were expected to enroll after completing the CP curriculum.

- Écoles Communautaire de Base (ECB), meaning “basic community schools” in French, were three-year programs established in communes with high numbers of out-of-school children and no formal schools. These served children ages 9-14 years old who had never attended school and needed foundational skills in reading and math. Upon completion, children could transition to nearby primary or middle schools. In areas lacking formal schools, Passerelles worked with government authorities to convert ECBs into government-run formal schools. Children who finished at an ECB could transition to primary (if younger than 12-13 years old) or middle school (if older than 12-13 years old).

- Daaras Communautaires are Quranic schools where parents send children ages 6 to 14 years old for religious education, including Arabic and Quranic studies. Daaras also educate orphans and other groups of vulnerable children, who live under the guardianship of a religious leader. Being an established institution in the Senegalese education landscape, Passerelles partnered with community and religious leaders to incorporate foundational French and mathematics into the daara curriculum. Children attending daaras could transition to primary or middle schools based on age or continue at the daara.

From inception, Passerelles recognized the importance of empowering the voice of families and communities and their ownership of education services. Before Passerelles started implementation in a community, project staff conducted extensive sensitization with the community, organizing forums and intergenerational dialogues to collaboratively decide what type of non-formal model was the most appropriate for the community. This approach ensured that needs and asset assessments were community-driven, and allowed parents, youth, and local leaders to play a role in supporting and holding oversight over the non-formal modality once implemented.

Across all modalities, Passerelles focused on equipping volunteer educators recruited from the communities with the necessary skills and resources to facilitate effective learning. This support enabled children to acquire foundational literacy and math skills, develop socio-emotional competencies, and learn in safe, nurturing environments.

Methods

We utilized administrative data on transitions and primary data from program participants and their caregivers. We obtained the data from local education authorities between 2018 and 2022, which allowed us to calculate the percentage of children who transitioned to a formal school out of the total number of participants in a non-formal modality until that period. Upon completion of a non-formal modality, local authorities assessed children and youth’s reading and math skills. Those achieving passing scores, indicating readiness for the formal system, were recommended for enrollment in local formal schools, with grade placement determined by age and proficiency levels. Children scoring below the passing threshold could continue attending the non-formal modality and be reassessed later. For a child to be counted toward transition, they must have been recommended for transition and enrolled in a formal school.

To explore the potential influence of student-level characteristics and other factors on transition, we analyzed data from structured surveys conducted with a sample of 658 non-formal modality participants, and their caregivers, as part of the project’s baseline and endline data collection. Student surveys examined participants’ experiences in the non-formal modality, future aspirations, and assessed their literacy, numeracy, and socioemotional skills. Parent surveys explored views and preferences regarding their children’s education. Additionally, follow-up qualitative interviews were conducted with 130 students six months after completion of their modality: 108 who had transitioned to formal school and 22 who had not, to gain insights into their experiences.

How effective were the different modalities in promoting transition to formal school?

As illustrated in Figure 2, we found that nearly one-third (32%) of participants had successfully transitioned to a formal school, with significant variation between modalities. The overall transition rate across Classes Passerelles, Daara Communautaire and Ecole Communautaire de Base is 32%, with large variations between modalities. The transition rate is highest for CP at an average of 55% across all cohorts, 34% for ECB and 18% for Daara.

What explains these transition rates?

Children’s outcomes

While children who participated in non-formal modalities in general showed considerable improvement in their reading and math skills from baseline to endline, students who transitioned were precisely those who had stronger literacy and numeracy skills. In-depth analysis of the endline results from Classes Passerelles students (the modality for which we have the most participant data) revealed that those who made the transition had scores that were 15-18 percentage points higher in their composite reading and math scores than those who did not, a statistically significant difference. This makes intuitive sense considering that transition was dependent on their ability to pass the test administered by local education authorities.

Soft skills also seemed to correlate with transition. Learners across modalities who transitioned were more likely to have higher self-efficacy scores (i.e., their belief in their own ability to succeed), even when controlling for academic achievement. Additionally, non-formal program participants showed reduced tendencies towards aggressive conflict resolution, lower rates of experiencing violence in school environments, and increased awareness of violence reporting mechanisms. While we cannot identify statistically significant differences among students who transition and those who did not, promoting safer environments remains critical to ensure that children feel welcome in non-formal education settings, preparing them for a potential transition to a formal school environment.

Modality design and implementation

The design of each non-formal modality and the realities of implementation played significant roles. Classes Passerelles were established where formal schools did exist, which may have facilitated the transition. Conversely, ECB were established in communities with no formal schools, with students being able to transition into a formal school by either attending a school in a neighboring community or by the government transforming the ECB into a formal school. Notably, the project worked with local authorities to successfully transform 11 out of 19 ECBs into formal schools, with others awaiting conversion – suggesting potential for higher transition rates from this modality.

Parental preferences continue to influence formal school enrollment decisions, especially among parents and caregivers of children attending a daara. For some of them, the existence of daaras is intimately linked to what they see as the cultural and religious identity of their communities, even if they recognize the importance of formal schooling. As one parent from Kolda explained in an interview, “if all the children go to formal school, the daara will close, and not a single learner will remain in the daara. That’s why we’ve divided up the children. Some go to elementary school; others go to the daara. If everyone goes to [formal] school, there won’t be anyone left to learn or teach the Quran at the daara.” This view points to the need to continue the work with religious leaders to infuse quality and relevant content into the curriculum of daaras.

Context-specific barriers

Finally, context-specific barriers to transition persist. With many households living in poverty, children and youth must still work to supplement their family’s income. While the non-formal modalities implemented by Passerelles were designed to be flexible and aligned with the schedules of working learners, many simply cannot attend consistently. For those who could attend and transition, parents may face difficulties in paying for school materials or fees, which may lead them to not enroll their child. Many parents also remain unaware that their children could transition to a formal school, indicating that more could be done to educate parents on options available to their children. Moreover, the distances between formal schools and the home villages of children are long and contain many dangers, such as road traffic and river crossings. This also makes some parents more likely to want their children to stay in their own community for safety.

What does this mean for future programming?

First, non-formal modalities must be tailored to diverse profiles of out-of-school children and youth, ensuring that that all children are provided with opportunities for learning and continuing their educational trajectories. Passerelles’ experience incorporating French and math instruction in the curriculum of daaras shows that interventions must rely not only on solid design, but on implementation that recognizes key stakeholders and relevant institutions to reach participants. Community engagement is crucial from early stages, allowing parents, youth, and local leaders to be involved in selecting, shaping, and ultimately holding ownership over the non-formal education programming.

Second, transition should be viewed holistically, not solely as a function of program participation and children’s academic outcomes. At the student level, our results highlight the importance of socio-emotional skills, in addition to literacy and numeracy, in successful transitions. Non-formal programming should incorporate strategies for development of skills, such as self-efficacy and conflict resolution, while also fostering safe learning environments for participants. These skills are not only critical for children’s transition into formal school but in their life-long success.

More broadly, our analysis points to the need to recognize the role that socioeconomic conditions play in influencing transition outcomes. Non-formal programming should explore ways to offset opportunity costs for families and work with communities and authorities to promote flexible arrangements to increase attendance among children and youth who may already engage in economic activities.

Lastly, post-transition support should be a key component of any programming seeking to ensure that children can thrive after participation in a non-formal model. In formal schools supported by Passerelles to host integration events for new students, provide ongoing academic and social support, and engage families to ensure sustained enrollment, children felt encouraged and ready to continue their educational trajectories.