Overweight and obesity are increasingly prevalent globally. As reported by the World Health Organization, the estimate for overweight and obese children in 2019 was 38.2 million, with the number in Africa increasing by nearly 24% from 2000 to 2019. Ford et al. (2017) call obesity in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) an “epidemic” while noting that evidence about effective strategies to prevent obesity in LMICs is limited (p. 1). In a recent post, we present a rapid evidence review conducted in the summer of 2019 on interventions to address the dual burden of malnutrition. Within the rapid review, we include 13 systematic reviews that focus on LMICs, and as was the case throughout the review, most of the included studies only cover obesity. In this post, we summarize findings from these 13 systematic reviews about what works to prevent and treat obesity in children in LMICs.

Methods

We searched the PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and POPLINE indexes and through the EBSCO portal an additional seven indexes using a search strategy with terms for malnutrition, obesity, programs and interventions, and systematic reviews and evidence maps. We also searched 16 websites, most of which house reviews and maps. A single reviewer screened each record at each stage, although we discussed and came to agreement in all instances of uncertainty. Key exclusion criteria were: published before 2004; only covering undernutrition; not covering intervention or effectiveness studies; only covering pharmaceutical or surgical interventions; and not covering any of our target populations (neonatal through youth plus maternal). While we conducted the full-text screening, we used the tagging feature in Covidence to code the reviews for whether 10% or more of their included studies were conducted in LMICs.

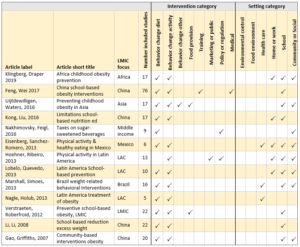

Once we had the included studies, we coded each along several dimensions, including study features, participants, intervention types, intervention settings and outcomes. Study features included a binary code for LMIC focus. The studies coded as having LMIC focus have a stated LMIC focus, are restricted to regions with many LMICs, or cover only specific low- or middle-income countries. The sets of intervention types and settings are shown in table 1 below. For outcomes, we simply coded for whether the outcomes analyzed in the review are biological, behavioral or other.

We also conducted critical appraisal using the ROBIS tool. The critical appraisal ratings include the three ROBIS categories – low risk of bias, unclear risk of bias, high risk of bias.

Results

The full-text screening yielded 210 studies based on the pre-stated inclusion and exclusion criteria. Given that we had only six weeks to complete the review, we then weened out all systematic reviews that were not tagged as having 10% or more of their included studies from an LMIC. We were not able to make this distinction for the umbrella reviews, so we kept them all in. After this final cut, we had 66 systematic reviews and 12 umbrella reviews. Our companion post provides the complete PRISMA flow diagram.

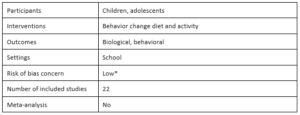

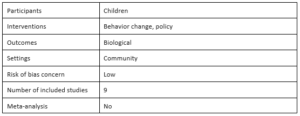

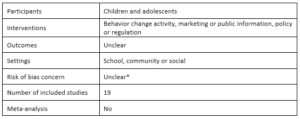

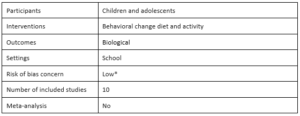

Among the 66 included systematic reviews, there are 13 reviews with an LMIC focus. Table 1 lists these reviews along with information about the interventions and settings they cover.

The interventions most covered in the LMIC systematic reviews are those designed to change behavior, either diet (nutrition) or physical activity. Many reviews look at both. Not surprising given that the rapid review centered on young people, school is the more common setting for the interventions studied, and community or social is the next most common. A few of these reviews have a relatively small number of included studies, for example the Nagle et al. (2013) study for Latin America only includes five studies. Roughly half of these reviews only cover a single country, including four for China.

Summaries of included multi-country LMIC systematic reviews

We selected for narrative summary those seven systematic reviews from the LMIC subset that cover more than one country. (We summarize one of the China reviews, which covers undernutrition and overnutrition, in our companion post.) Each summary includes a table (un-numbered) of summary information.

Childhood obesity prevention in Africa: A systematic review of intervention effectiveness and implementation by Sonja Klingberg, Catherine E. Draper, Lisa K. Micklesfield, Sara E. Benjamin-Neelon and Esther M. F. Sluijs, 2019

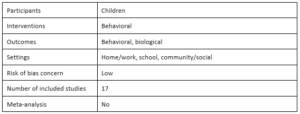

The focus of Klingberg et al.’s systematic review is on behavioral interventions for preventing childhood obesity in African countries. The 17 included studies cover 14 different interventions from three African countries: South Africa, Tunisia and Uganda. The authors summarize the intervention effects and quality of each study in their table 3. The authors conclude that behavioral childhood obesity prevention interventions have no overall effect on dietary behaviors, but there are some beneficial effects of school-based interventions on physical activity and anthropometric outcomes in South Africa and Tunisia. However, they assess the methodological quality of all studies as weak. By reviewing also process evaluations, the authors identify barriers to implemented school-based interventions as largely resource-related, including lack of time from teachers and stakeholders, buy-in, training or motivation.

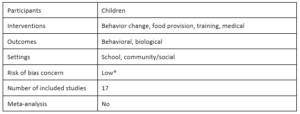

Preventing childhood obesity in Asia: An overview of intervention programmes by L. Uijtdewilligen, C.N. Waters, F. Müller-Riemenschneider and Y.W. Lim, 2016

Uijtdewilligen et al. provide an overview of childhood obesity interventions in Asia. The included studies are mostly from China and Thailand and are school-based. The authors find that the effects of interventions on overweight and obesity prevalence, incidence, or remission; body mass index (BMI); waist circumference; or fat mass are mixed. However, they do report that the “most substantial effects were found for outcomes such as improved health knowledge and/or favourable lifestyle practices,” (p. 1103) suggesting that there is some efficacy for childhood obesity interventions in Asia in terms of behavioral outcomes. The majority of included programs combine more than one intervention type, but the authors are unable to identify effective program components due to differences in intervention design and no separate statistical analyses of each component.

Effectiveness of preventive school-based obesity interventions in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review by Roosmarijn Verstraeten, Dominique Roberfroid, Carl Lachat, Jef L. Leroy, Michelle Holdsworth, Lea Maes and Patrick W. Kolsteren, 2012

Verstraeten et al. focus their review on the effectiveness of school-based dietary behavior or physical activity interventions on obesity prevention in children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries. To measure the impact of interventions, the authors analyze outcome differences between the intervention and control group over time (double difference effect) and between the intervention and control groups at follow-up, adjusted for values at baseline (baseline-adjusted effect). The authors conclude that in general, school-based interventions have a positive effect on dietary and physical activity behavior and decrease BMI. They also note that the overall low methodological quality of the included studies does not affect this conclusion, given the consistent positive effects across studies and that the largest effects were found from high quality studies. The authors describe characteristics of interventions that positively changed outcomes to include both diet and physical activity, involve multiple stakeholders, and integrate educational activities into the school curriculum.

Taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages to reduce overweight and obesity in middle-income countries: A systematic review by Sharon S. Nakhimovsky, Andrea B. Feigl, Carlos Avila, Gael O’Sullivan, Elizabeth Macgregor-Skinner and Mark Spranca, 2016

Nakhimovsky et al. review the effectiveness of sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) taxation in middle-income countries on price of SSBs, net intake of excess energy and obesity rates. This review includes studies from Brazil, Ecuador, India, Mexico, Peru and South Africa. The authors consider three of the nine included studies high quality, two of which focused on Mexico and the other on Peru. The authors conclude that SSB taxation increases the price of SSBs and reduces net energy intake. Specifically, they find a “decrease in SSB consumption ranging from 5 to 39 kilojoules per person per day given a 10% increase in SSB prices” (p. 1). However, these findings are based on a small number of studies most of which are low quality. Additionally, while this reduction in net energy intake is enough to prevent further growth in obesity prevalence, the authors acknowledge that it is not enough to permanently reduce population weight. The authors also find that milk is a possible substitute for SSBs and that “food prepared away from home, snacks and candy are likely complements to SSBs” (p. 1).

Physical activity interventions in Latin America: Expanding and classifying the evidence by Christine Hoehner, Isabela C. Ribeiro, Diana C. Parra, Rodrigo S. Reis, Mario R. Azevedo, Adriano A. Hino, Jesus Soares, Pedro C. Hallal, Eduardo J. Simões and Ross C. Brownson, 2013†

In this review, Hoehner et al. update an earlier review to build the evidence base for physical activity interventions in Latin America, especially in Brazil. In addition to the standard coding and appraisal for internal validity, they develop and employ an external validity assessment tool to appraise the external validity of the included studies. This tool assesses whether the studies include specific features that make the findings more externally valid. They then rate the evidence for different interventions using a combination of study findings, internal validity assessment and external validity assessment. They conclude that school-based physical education is “evidence-based”, which is consistent with the findings from the earlier review. They rate community-wide campaigns and point-of-decision prompts as “promising”, as well as physical activity classes in community settings and multicomponent instructional programs.

School-based programs aimed at the prevention and treatment of obesity: Evidence-based interventions for youth in Latin America by Felipe Lobelo, Isabel de Quevedo, Christina K. Holub, Brian J. Nagle, Elva M. Arredondo, Simón Barquera and John P. Elder, 2013

Lobelo et al. conduct this review using a subset of studies from a much larger parent review. They select the subset using inclusion criteria to look at the impact of school-based prevention and treatment behavioral interventions on youth obesity-related outcomes in Latin America. The authors find that although only three of ten studies tested treatment interventions, two of the three find significant positive effects and were appraised to have “adequate design quality and execution” (p. 675). They also conclude that there is sufficient evidence supporting prevention interventions that promote both physical activity and healthy eating in school settings and argue that this finding has external validity because there are similar results across different countries.

Interventions for the treatment of obesity among children and adolescents in Latin America: A systematic review by Brian J. Nagle, Christina K. Holub, Simón Barquera, Luz Maria Sánchez-Romero, Christina M. Eisenberg, Juan A. Rivera-Dommarco, Setoo M. Mehta, Felipe Lobelo, Elva M. Arredondo and John P. Elder, 2012

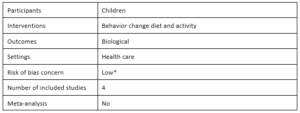

Nagle et al.’s review seeks effective interventions delivered in health care settings for the prevention and treatment of childhood obesity, focusing on studies from Latin America. The authors conclude that generally, “there is evidence that interventions in the health care setting can be effective in creating positive anthropometric changes in overweight and obese children” (p. S434). However, this conclusion is based on only four included studies. They classify one study as good quality and three as fair quality based on the number of limitations and study design. Nagle et al. find that all four studies measure statistically significant changes in BMI, and three studies showed significant changes in weight. They also report that interventions that combine physical activity and healthy eating resulted in larger effects on anthropometric changes.

Discussion

The systematic reviews of obesity prevention and treatment interventions for children, youth and maternity in LMICs cover four of the settings typically considered: school, home, community and health care. Of the seven included LMIC reviews, one covers all LMIC, one middle-income countries, one Africa, one Asia, and three Latin America. Even though several of the reviews were appraised as having a low concern for bias and they all measure biological outcomes, none of the reviews include meta-analysis, due to the heterogeneity among interventions and study designs. The low concern for bias appraised by us mostly reflects that the review authors carefully appraise and account for the quality of their included studies, even though those primary studies are often of low quality.

Limitations

This review is limited by the methods we used for rapid evidence reviewing. Our search was restricted to systematic reviews and was narrower than for a full systematic review. The screening and coding tasks were conducted by a single reviewer with concurrence in cases of uncertainty. Because we searched for reviews, the evidence included here is more dated than if we had searched for primary studies.

Although we found seven systematic reviews that focus on LMICs and include more than one country, the country coverage across the full set of LMICs is small, and there is wide heterogeneity across countries and regions. Nonetheless, it is encouraging that the general findings for school-based interventions for obesity prevention are similar across the reviews.

*This systematic review was not critically appraised for the rapid review. We appraised it for the purpose of this blog post.

†This summary does not appear in the rapid evidence review. We wrote it for this blog post.

Photo credit: Issaret Yatsomboon/Getty