By: Annette N. Brown with Katherine Whitton

One of the great things about working in international development is engaging with research across a variety of fields. Development is inherently multi-sectoral. I am an economist and was thus raised in the research culture of the social sciences. But I’ve been fortunate to engage quite a bit in the last decade with public health research, even co-authoring a number of studies published in public health journals. As a funder (in my previous job) and author of publications in both social sciences and public health, I’ve been struck by differences in culture and practice between the two. These differences are understood anecdotally by many, but I wanted to see some data.

In this post and a companion post, I present the research I conducted with Katherine Whitton comparing public health and social science publication practices for development impact evaluations.

Methods

Development impact evaluations serve as a useful subset of research for comparing public health (or health science) and social science research. Impact evaluations are defined according to the methods of measuring a net attributable impact of a treatment, program or policy, and these methods are applied similarly (but not identically, as explained by Powell-Jackson et al., 2018) by both public health researchers and social scientists.

At the close of the update, there were more than 4,000 records in the registry. We drew a random sample of 10% of those records in order to code additional data from each study. For the purpose of the health science vs. social science analysis, we then restricted the sample to those studies published or posted from the years 2000 through 2014 so that we would have three complete five-year cohorts. We obtained the full text for each study and coded the following information: the gender of each author, the country of primary affiliation of each author and the date of end-line data collection. We also coded each of the journals, working paper series and institutions publishing reports as being “health” or “social science”. Later in this post, I’ll talk more about what we learned from the process of coding gender.

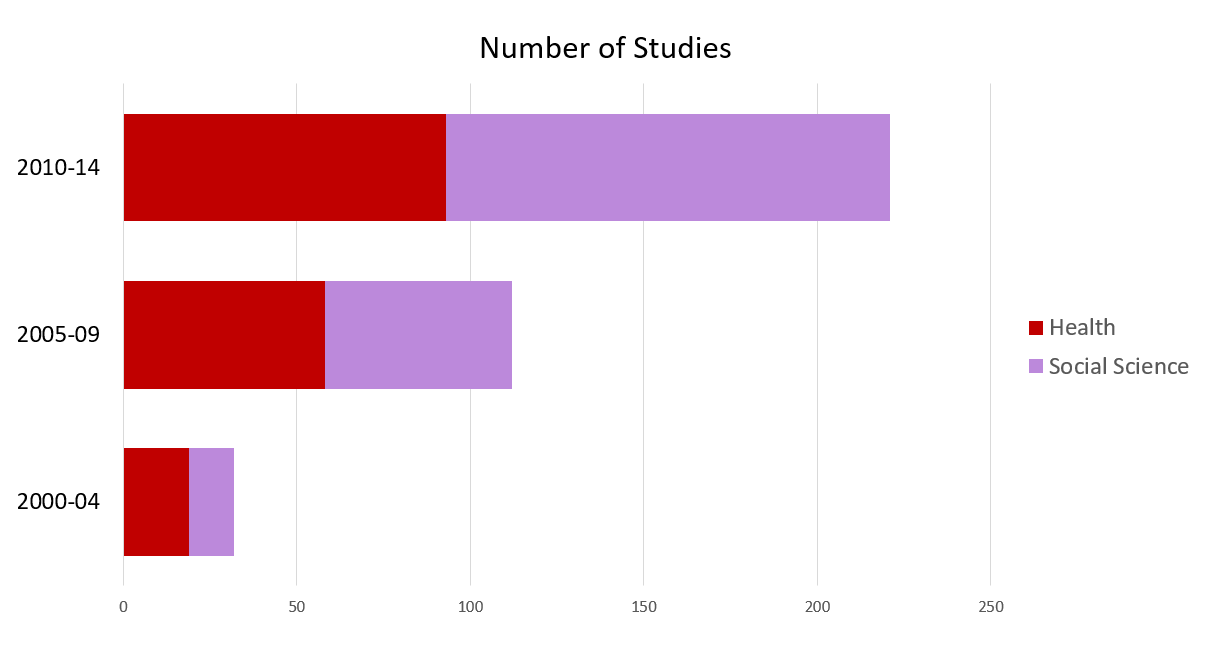

For the analysis of time trends, we examined three five-year cohorts: 2000–2004, 2005–2009 and 2010–2014. Figure 1 below shows the growth in the number of development impact evaluations over those time periods as well as the relative share of health science and social science studies. In the whole sample, there are 197 health studies and 217 social science studies. I report the findings from the analysis of the author information in this post and the analysis of the end-line data collection data in another post.

Findings

The average number of authors per study across the whole sample is 4.6, but the average for those in health journals is 6.5 while for social science outlets is just 2.8. The most authors – 17 – in the sample is for an article published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute. No social science study has 10 or more authors, while 38 health studies have double-digit numbers of authors. These findings are not surprising to those familiar with research across these discipline groups.

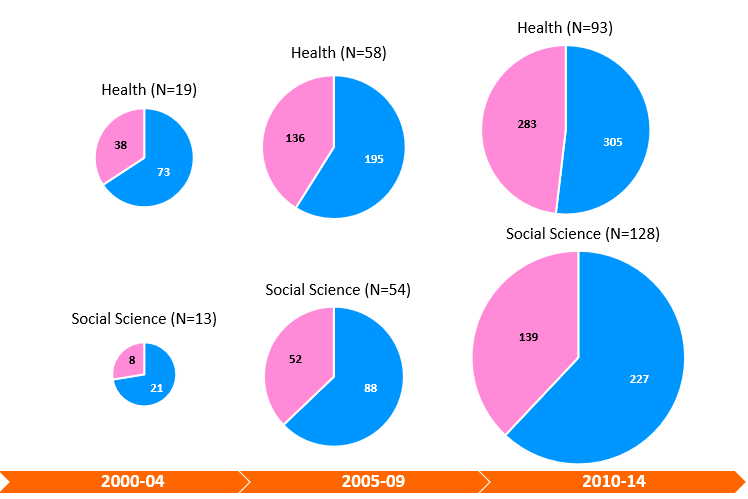

In figure 2, we show the authorship shares by gender of the authors. The “N=” number is the number of studies represented in each pie chart, and the numbers in the pie pieces are the numbers of authors. The pink pie pieces (on the left) report the number of women and the blue, men.

For both health and social science, the share of women increases over the three cohorts. For health the share grows from about one third to nearly half, while for the social sciences it grows from about a one fourth to about one third.

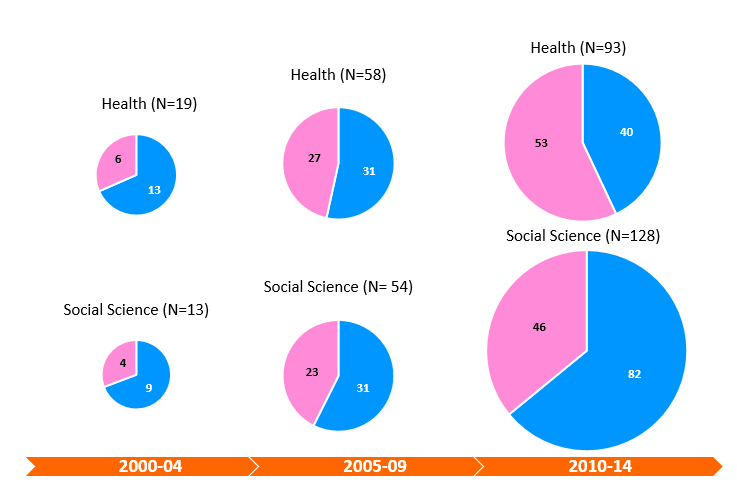

We conducted the same analysis but just for the first author of each study, shown in figure 3.

Here it appears that the health sciences have made more progress than the social sciences. In the last cohort for the health sciences, the share of studies with female first authors is actually greater than the share of female authors, and also greater than 50%. On the other hand, in the most recent cohort for the social sciences, the share of studies with female first authors is similar to the share of female authors, and still well under 50%.

The comparison is a little more complicated, though, as author order works very differently in the two sets of disciplines. As has been explained to me, author order for the health sciences has always signified contribution, with the first author being the primary author and so on EXCEPT that when there is a laboratory or similar large team, the laboratory director is then listed as the last author. So (bizarrely to the uninitiated) both first author and last author hold the most prestige. On the other hand, in the social sciences (or in economics at least) the common practice for many years was to list the authors in alphabetical order. This practice probably originated from an assumption that if more than one author was listed, they must each have contributed relatively equally. (My former frequent co-author J. David Brown often cursed this practice.) Over time, the practice has changed, and now author order typically reflects contribution, but without the significance of the last author.

For the public health studies, the share of female last authors has increased from 12% to 21% to 40% over the three cohorts.

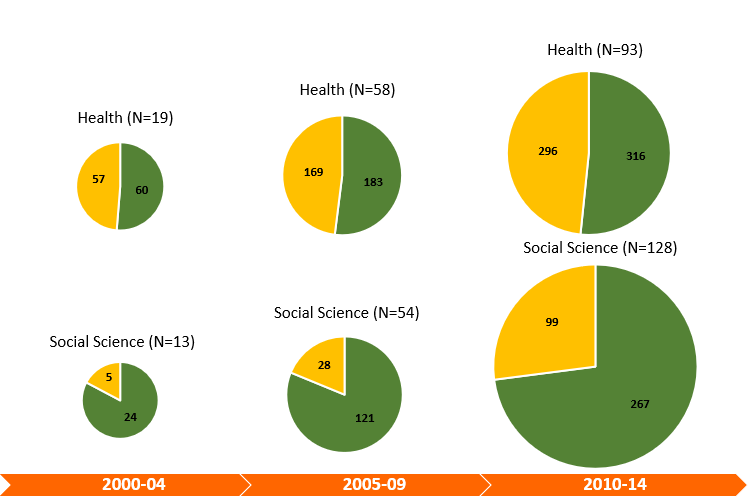

Finally, we look at the income status for countries of primary affiliation for each author. In figure 4 below, the yellow pie pieces (on the left) represent authors from low- and middle-income countries and the green pie pieces represent authors from high-income countries.

Even in the first cohort, and consistent through time, the public health development impact evaluations have roughly equal authorship from low- and middle-income countries as from high-income countries. In the social sciences, the share of authors of development impact evaluations from low- and middle-income countries has grown, but in the most recent cohort, the share is only roughly one quarter. The shares are essentially the same when we look just at first authors.

Discussion

The findings in figures 2 and 3 are consistent with the conclusion that women have made more inroads into publishing in public health than they have in the social sciences. This could reflect either an increasing share of women in public health fields over time or decreasing discrimination against women in these fields, or, most likely, some combination of the two. The finding that the share of female first authors in public health studies increased even more than the share of total authors could point to reduced discrimination.

When looking at the social sciences, it is important to note that economists are heavily “over-sampled” in the IER due to the methodological requirements for studies to be included. So, the findings largely reflect the experience of economics. Wang et al. (2019) calculate author share by gender for publications in JSTOR across multiple disciplines and find that economics has a lower share of females than sociology, demography and anthropology, although not much lower than political science. (See the figures in the supplemental materials at the end of the paper.) The share of female authors in economics in JSTOR is much lower than for the social sciences in our sample, however, which suggests that there are more women publishing in development economics than in the economics field generally.

The Wang et al. study does not include the primary public health fields (e.g., epidemiology) but comparing our findings for development impact evaluations in public health against the basic science fields in Wang et al., we see a much higher share of female authors in public health.

One likely explanation for the differences in income status shares between health and social science shown in figure 4 stems from the very different co-authorship practices in the disciplines. Health research articles are known for having a large number of authors. Our data reflect this; the average number of authors for the health impact evaluations is more than double that for the social science studies. In fact, the practice of including many research team members as authors has led some public health journals to write policies for minimum qualifications for authorship and requirements to list the contributions of each author. (See an example here.)

This practice makes it easier for public health researchers to include as authors members of their research teams who serve in a variety of roles, including those involved in program implementation and data collection. The implementers and data collectors are more likely to be from the country of study, regardless of where the other authors are from, meaning that adding these team members increases the share of authors from low- and middle-income countries.

On the other hand, in the social sciences, at least in economics, multiple authors can diminish the value of a publication to a researcher’s publication record, which can be very costly to junior researchers working towards promotion. Principal investigators guard co-authorship carefully. Also, it is often expected that any co-author must have made a roughly equal contribution, even as author order has begun to allow for better signaling of contribution. I was once talking to a well-known full professor in a social science field about his work in a low-income country, and I asked him why he wasn’t adding any of the local researchers as co-authors. He responded that anyone named as co-author needs to be making an intellectual contribution to the study equal to his own and that wasn’t the role of the local researchers for this study.

There are increasing pressures across disciplines, however, to reduce the domination of Western scholars in research about development. Funding organizations are directing funding to low- and middle-income country research institutions or prioritizing collaborations between international and host-country principal investigators, where all make substantive contributions. Many researchers recognize that having multiple co-authors who each bring clear benefits (methodological, sectoral, contextual) to the study can increase the credibility of findings. And host-country co-authors are often critical for policy influence. This insight paper and this editorial discuss the challenges of local authorship and provide useful recommendations.

An aside on identifying author gender

For this research, we coded author gender manually. The intent of our coding protocol was to code for the author’s gender identity at the time of coding and not sex at birth, but our judgments were mostly based on given names with a small number of cases based on pictures. For given names that are not familiar, we used baby name sites to determine whether the name is primarily associated with a gender. If we were not able to code by name, we looked at the LinkedIn page, if available, or other internet hits for the author to try to find a picture or a gender identifier. For a few cases, we found online mentions (e.g., university announcement) that used a gendered pronoun.

There were two main causes for missing data on gender. The first was given names that are not highly gender specific. In these cases, we did try looking up the specific researcher. The second, which was extremely frustrating, was journals that only publish initials for given name(s). I don’t know where or how this practice initiated. I can imagine an argument that it reduces the ability of readers to discriminate based on gender, but it seems to me that the greater discrimination happens in the many stages before articles are actually published. On the other hand, the practice makes it very difficult for metascientists to study gender in science. David Wojick makes a good argument that it is also detrimental to many international researchers.

Conclusion

Katherine Whitton performed much of data coding and graphical analysis for this research. I would also like to acknowledge Shayda Sabet, who assisted with a first round of coding for this sample and contributed to early discussions of the analysis. The supplementary materials for this research are available here.

Photo credit: yanalya/FreePik