Recently, at the Society for International Development – Washington annual conference, I bumped into a former colleague who exclaimed, “I follow you on LinkedIn, and I love your theory of change article!” This comment reminded me that I need to be better about updating my LinkedIn page, but it was also great to hear that an old 3ie blog post of mine – three years old now – is still being read. The ideas in that post are also the foundation for a workshop I’m delivering at What Works Global Summit and Evaluation 2019. In anticipation of that workshop, we at R&E Search for Evidence thought we’d dust off the article and cross-post it here. I’d love to hear from readers their examples of when a logical framework didn’t match the theory.

The formatting and spelling in this post appear as originally produced by 3ie.

Anyone who has ever applied for a grant from 3ie knows that we [3ie] care about theory of change. Many others in development care about theory of change as well. Craig Valters of the Overseas Development Institute explains that development professionals are using the term theory of change in three ways: for discourse, as a tool, and as an approach. And indeed a Google search for theory of change in international development returns images of elaborate diagrams of logical frameworks, long documents describing policies and approaches, manuals presenting tools, and blog post after blog post. Theory of change has come to mean many things to many people, and in the process it has lost its soul: theory.

What is theory?

Academic circles take the concept so much for granted that I had to go looking for a good definition. I found this one: a theory is ‘a well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the world, based on a body of facts that have been repeatedly confirmed through observation and experiment.’ (Thank you, Wikipedia.) Wikipedia goes on to explain, ‘The strength of a theory is related to the diversity of phenomena it can explain, which is measured by its ability to make falsifiable predictions with respect to those phenomena. Theories are improved (or replaced by better theories) as more evidence is gathered, so that accuracy in prediction improves over time…’ This definition reminds us about what is needed for an explanation to be considered a theory and also why theories are so useful. A well-founded theory is one based on evidence gathered over time, and it can be used to make predictions. This predictive power of a theory, which we get from repeated tests of it, is a key element to establishing external validity, or the ability to apply what we learn about what works from one situation to another.

Assumptions ≠ theory

From arrows and assumptions to theory

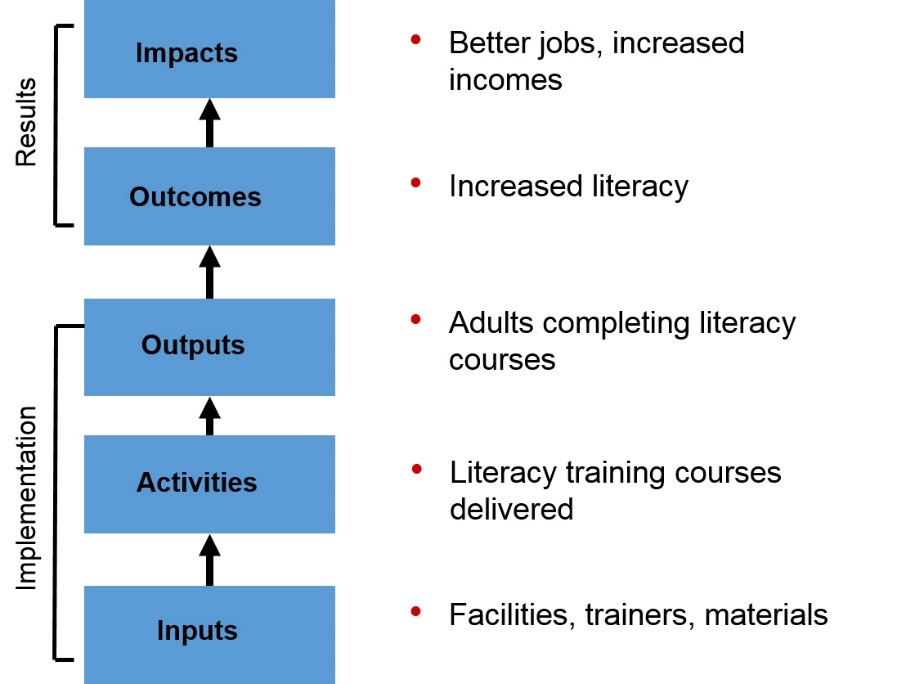

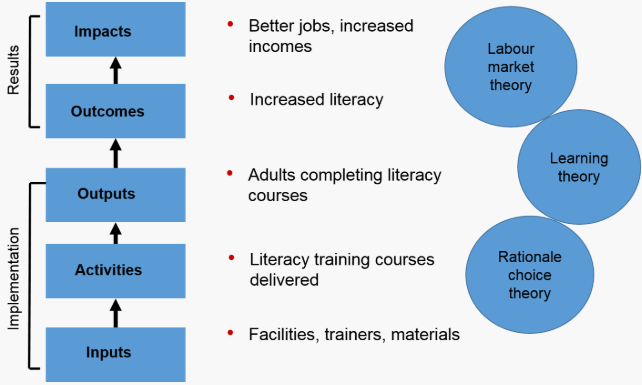

The figures below depict the distinctions I am making. Figure 1 shows a logical framework for a programme to provide literacy training to adults. Figure 2 shows some of the assumptions that we make in following the logic of the arrows in the framework. Figure 3 shows the underlying theories that explain (or predict) whether the programme will work.

When we think about the programme in terms of the theories underlying the causal chain, we have a richer picture of what is required for the logical framework to work. We should not just assume that adults will seek training to become literate. We should understand how they are able to optimise their welfare in their current environment. This allows us to predict whether they will make the investment in literacy training as the result of a rational choice. We should not just assume that any training about reading will lead to literacy. We should understand how adults learn to read so that we can design a training programme most likely to achieve an improvement in literacy outcomes. We should also not just assume that individuals who learn how to read will be able to find and get better jobs for higher incomes. We should understand the features of the local labour market so that we know there is an excess demand for literate workers at jobs with higher wages. We should also understand the local labour market well enough to predict whether or not an influx of new literate workers will drive down wages.

You may be thinking that’s a lot of theories for one simple programme. You are right. Development is complicated.

How we get it wrong when we ignore theory

Here are two examples of how we can get things wrong when we ignore theory. The first example is an edutainment intervention. I am on the research team for the impact evaluation of a television soap opera designed to address violent extremism (not funded by 3ie). When we began to design the impact evaluation, we looked carefully at the programme – the television programme, that is. The outline was the same as any soap opera. There are bad people; there are good people; as viewers, we are supposed to dislike the bad people and like the good people. I wondered, why should we believe that bad people viewing this soap opera will dislike the bad people and change their own behaviour as a result? I never became a better person from watching all those episodes of All My Children in graduate school.

I looked to my own discipline, economics, for an explanation and couldn’t find one. I turned to my political scientist colleague on the study team. He didn’t have an explanation either. So we turned to psychology. It turns out the theories in psychology do address how observing others’ behaviour might influence our own, but the theory supported by empirical evidence, i.e. social learning theory, does not support the standard soap opera approach. It predicts that we model behaviours we observe, but that we model both the good and the bad. There is no reason to predict that when we observe both the good and the bad in a soap opera, we only model the good, even when the bad might be punished. Instead social learning theory supports what my colleague and I call the Remember-the-Titans approach, where the drama depicts primarily the positive behaviour that we want observers to model (albeit with some tension to make the story interesting). After identifying the relevant theory, we suggested some changes in the soap opera story to the programme team.

The second example comes from the agriculture sector. An intervention that has been replicated in many countries over the years is the farmer field school. The farmer field school is a programme designed to increase the productivity of small-scale farmers by teaching them better agricultural practices, such as fertiliser use. The design of the training itself is based on adult learning theory. The premise behind the sustainability of the farmer field school model, and the claim for its cost effectiveness, is that there will be positive spillovers. Farmers who attend the school and learn the better practices directly will teach these practices to their neighbours who do not attend the school so that all farmers in the community will ultimately benefit from the programme.

The question is, why would any self-respecting economist predict that a rational agent who gains a productive advantage would share that advantage with her competitors? In fact many training programmes rely on the assumption that people who receive training will pass on that knowledge to others creating positive spillovers, or indirect benefits. For some kinds of training (e.g., political mobilisation, sexually-transmitted disease prevention) that assumption makes sense. But when markets are involved, we should not ignore competition unless we have a good reason to rule it out.

In the case of farmer field schools, a 3ie systematic review shows that the intervention produces positive outcomes for those who attend the school, providing evidence in support of the adult learning theory. But there is no evidence that neighbouring or non-participant farmers have improved outcomes, supporting, in a sense, economic theory.

Whose job is it anyway?

No, it doesn’t. Remember that a theory is an explanation that is repeatedly confirmed using experiment and observation. Whenever possible, we want to increase the return on investment from individual impact evaluations by having them contribute evidence that helps to improve the predictive power of these explanations, even where the improvement means showing that the theory is wrong or does not apply. The more evidence we can lend to theories, the better the theories we have for programme designers to use the next time around. If an impact evaluator cannot suggest a clear theory or set of theories on which the programme is based, then we need to recognise that this limits (but does not eliminate) what can be learned from that impact evaluation.

So what can we do?

Photo credit: Hero Images/Getty Images