Globally, 10% of people suffer at least one form of mental health disorder, and these disorders are increasing. Evidence shows that poor people are more likely to suffer from symptoms of mental health disorders because of exposure to stressful events, harmful living conditions, exploitation and poor health. Financial capability has a large influence on cognitive and physical health, data show (Adhvaryu et al., 2019). Because of this increase in mental health disorders, researchers are trying to understand the factors that trigger or mitigate symptoms. An article I recently read by Ajefu, Demir and Haghpanahan, “The impact of financial inclusion on mental health,” suggests that financial inclusion boosts mental health among Nigerians via pathways that include increased remittances and food consumption.

Methodology

Secondary data sources are used for this study.

The authors use data from two secondary sources. The first is the third wave of the General Household Survey (GHS) conducted in 2015/2016, which contains data on household and individual characteristics of 4,600 Nigerian families (including information on access to financial bank accounts and the rate of depression). The second is data on financial institutions collected by Insight2Impact (I2i), which contains information on the nature of financial institutions and their density in an area. I2i was a program sponsored by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to support policymakers, financial service providers and development partners to harness data in enhancing financial inclusion. The authors merge the datasets using geocodes that are common unifiers.

Measurement variables for financial inclusion and depressive symptoms are created using composite scores.

To measure for depressive symptoms, Ajefu et al. create two versions of the dependent variable using data from the Centre for Epidemiological Studies–Depression (CES-D) test. This test was administered to heads of household during the GHS. The first version of the dependent variable is the log of the composite score from the ten-item CES-D test, which ranges from 0 to 30. The second version is a binary variable—with a one indicating scores 10 and above on the test and zero indicating scores below 10. I report the first measure of depression in this post as I believe it gives a clearer picture of adverse mental health symptoms.

To measure financial inclusivity, the authors take their lead from other researchers (such as Zhang and Posso, 2019) who considered bank account ownership a sign of financial inclusion. However, they take an additional step, creating a financial inclusion score with three dimensions: bank account ownership, access to credit and access to insurance. These dimensions are each weighted one-third, and the authors consider households financially included if their score is higher than 0.5. They then create an indicator variable of one for families with a financial inclusion score higher than 0.5 and zero for below that. The descriptive statistics from their data show that 10% of families are financially included, 38% have bank accounts, 18% have loans from formal institutions and 3% report having access to formal insurance.

Their model controls for endogeneity

The authors acknowledge two ways that financial inclusion might be endogenous to mental health. First, mental health conditions are likely to influence the financial choices people make. Second, there may be multiple factors that influence both mental health and financial inclusion that are excluded from the model. To address the endogeneity problem, the authors use an instrumental variable, quasi-experimental design, with the distance to the nearest financial institution as the instrument for financial inclusion. They implement this approach using two-stage least squares (2SLS). The first stage estimates the effect of distance on measured financial inclusion, and the second stage uses the instrument to estimate the effect of financial inclusion on mental health.

What do their results show?

The authors’ results from their 2SLS estimates suggest a significant negative relationship between financial inclusion and mental health. Ajefu et al. find that, on average, financial inclusion decreases depressive scores by 96%. Their analysis argues that financial inclusion mitigates depressive symptoms by increasing food expenditure and remittances, with financially included households spending 380% more on food, on average, and 30% more on remittances, on average, than households that aren’t financially included.

The effect depends on the type of financial product.

Research by other authors (such as Aguila et al., 2016) has measured financial inclusion solely through bank accounts, while Ajefu et al. create a financial inclusion index by taking a weighted average of bank account ownership, access to credit and access to insurance. The authors disaggregate this score and find that the components have varied implications for mental health. Specifically, depressive scores for people with formal bank accounts were 32% lower than those without, 136% lower for owners of formal insurance in comparison of those who had none, and 227% lower among those who had formal credit compared to the scores of people without formal access to credit.

Financial inclusion helps mitigate depressive symptoms during negative shocks.

Put simply, negative shocks cause financial limitations in households; in this study, the authors use rainfall shocks as a measure for such periods. Previous research suggests that negative shocks adversely affect mental health. Ajefu et al. find that depressive scores are 66% higher during rain shocks, on average, for all households. However, during rain shocks, people with financial inclusion have depressive scores that are 659% lower, on average, than people without financial inclusion.

My thoughts on the authors’ methodological approaches

Secondly, I wondered why the authors weighed account ownership, access to credit and access to insurance equally in their financial inclusion score. In Nigeria, credit and insurance consumption are much less common than owning a bank account. A report by Efina shows that 55% of the adult population was banked in 2020. Of that group, 24% reported using a savings account through a formally regulated financial institution in the 12 months preceding the survey. The numbers were 3% and 2% for credit and insurance consumers, respectively, among banked consumers. Given these differences in usage rates, I am curious why the authors chose to use an equal weight for all three components.

Finally, throughout this post, I reference results from the first version of their dependent variable (i.e., the integer value). However, the authors also report results from version two of the dependent variable (i.e., the indicator variable). I wasn’t sure how to interpret these results because they did not fully explain the criteria for their cutoff for the indicator variable. With their cutoff, a person with a depressive score of 30 is grouped with someone who has a depressive score of 11. I wonder how this would affect the dispersion of their results.

Conclusion

Ajefu and colleagues provide one of the few analyses on the causal relationship between financial inclusion and mental health in Nigeria. Both subjects are quickly evolving, and studies such as this provide needed evidence for researchers working to think more creatively as they seek causal answers.

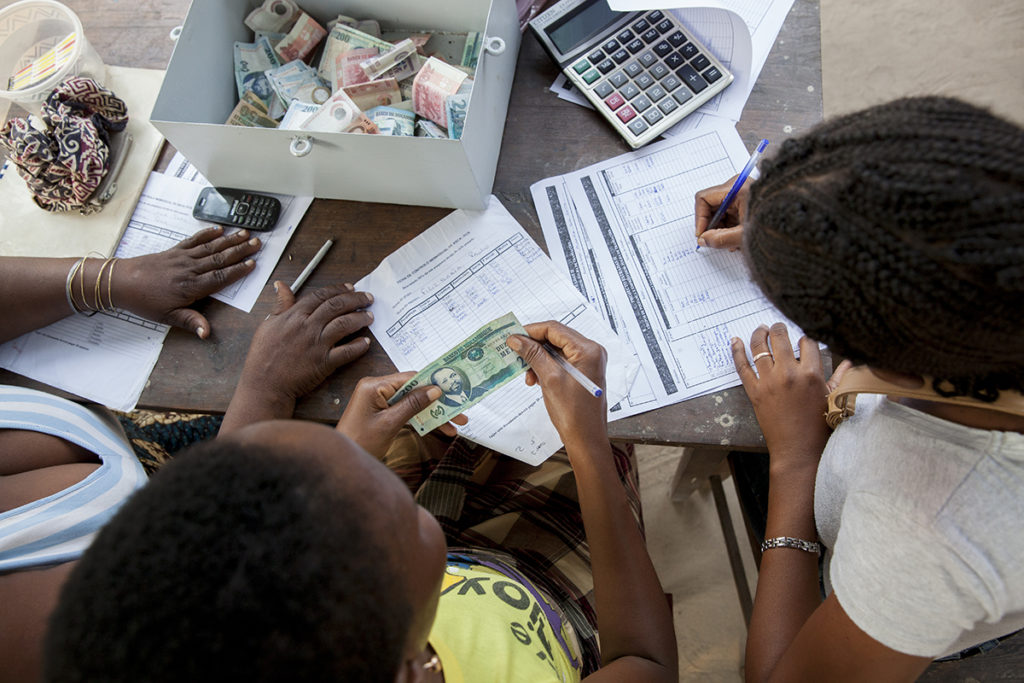

Photo credit: Jessica Scranton/FHI 360