Children who live outside of family care are highly vulnerable to a number of threats to their wellbeing: abuse and exploitation, health and behavioral problems, and problems developing relationships and a positive sense of self (Laumann, 2015). While poverty is not the only cause of child separation from family care, it is often a primary driver that interacts with other factors to weaken families and increase the likelihood of child separation. It makes sense then that to prevent family-child separation – and to support families reunified after a separation – family support programming should include some type of activity or intervention aimed at improving the family’s economic situation. The question is whether, which and when household economic strengthening (HES) activities could be appropriately and effectively incorporated into family support. And, as importantly, how and why HES might work.

These questions were posed by USAID’s Vulnerable Children Fund (formerly Displaced Children and Orphans Fund, DCOF) to the Accelerating Strategies for Practical Innovation and Research in Economic Strengthening (ASPIRES) project. Over the course of the past four years, Lisa Laumann and I were part of a small team that conducted a range of research and evaluation activities to attempt to answer those questions and to develop guidance for practitioners on the selection and integration of appropriate economic strengthening activities to support family unity. In their October newsletter the Better Care Network helped us to share the resulting resource guide, Meeting the Costs of Family Care: Household Economic Strengthening to Prevent Children’s Separation and Support Reintegration, as well as many of the research reports and other program documents that supported its development. In this post I’ll focus on a practical section of the guidance document, the HES Activity Selection and Planning Tool, and describe how research and evaluation activities were necessary to and facilitated its development.

Starting with the end in mind

From the beginning of the project, we knew that our task was to help practitioners in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) who support family integrity by identifying and building evidence around which HES activities work for which types of families and in what situations. Given this focus on context, we had no illusions there would be a “one-size-fits-all” approach, but the complexity of these situations was made very clear when we started trying to understand how drivers of family-child separation interacted or layered upon one another to result in a child living outside of family care.

We began, unsurprisingly, with a review of the literature. From this we compiled an initial list of family characteristics and constraints associated with child separation. However, much of the prior evidence comes from Eastern Europe where countries have a long history of state-sanctioned institutional care that has facilitated separation, a very different context than LMICs in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

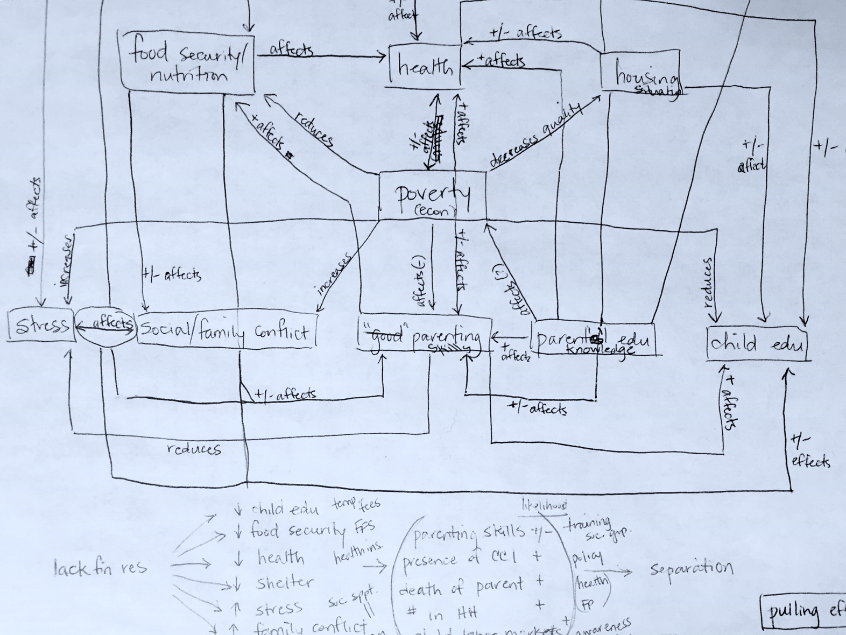

So, as part of a scoping trip to understand the landscape of programming in sub-Saharan Africa, we talked with practitioners from a half dozen implementing organizations to see how their understandings of separation drivers aligned with those we’d found in the literature. While some of the emphases and cultural contextual details differed, what was evident across contexts was that financial constraints, influencing and influenced by a number of other factors, usually played a role in child separations. Less evident from our conversations was a way to depict the nearly infinite number of possible combinations of family configurations, characteristics and capabilities that could make a family vulnerable (or resilient) to separation. Figure 1 shows my sad first attempt.

The messy middle

Having realized the improbability of developing a decision-tree “if-this-then-that” format to help match specific families with HES activities, we continued on in two directions to learn more about drivers of separation and potentially appropriate and effective programming to mitigate them. On one side, we invested in two learning projects (called Family Care), both implemented in Uganda with a diversity of family and child situations represented among participating families (e.g., in urban and rural environments; with children at-risk of separation; and with children recently reunified from a childcare institution or after living on the streets). The two projects implemented a range of HES activities – cash transfers, savings groups, matched savings accounts to support education, financial literacy and business skills – matched to the particular circumstances and capacities of these families, together with family and social support interventions and case management.

Concurrently, we took a broader, more global approach to understanding how HES might augment programming to support prevention of child separation or the reintegration of families. In late 2015 we fielded an online survey of practitioners to identify organizations that were already implementing HES activities in reintegration and prevention of separation programming. The 59 respondents represented 44 organizations spanning UN/international aid missions to small NGOs and provided information on program focus, types of HES activities and how they understood HES activities to affect reintegration and prevent separation. This survey was followed by in-depth interviews with over a dozen programs in as many countries to gather further practitioner perspective on how (effectively) HES was being used in support of family unity.

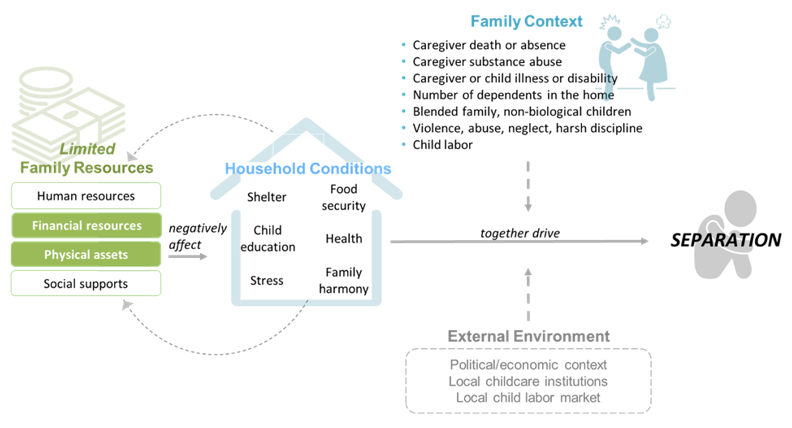

Together, these sources of information helped to solidify our understanding of the relationships among drivers of separation. Moving from left to right in Figure 2, and starting with the assumption of limited family resources, we mapped how limited resources can negatively affect household conditions and can, in combination with specific factors of family context and external environment, drive child separation. The combination and relative strength or weakness of capacities and resources will be different for each family, but severe constraints in any one of these areas will likely have ramifications for household conditions, which can be further exacerbated by challenges with family context and external environment.

For example, if a family has limited income and savings (financial resources), this will likely affect food security and ability to pay for school fees (household conditions). If that same family also has a single adult caregiver as a result of the death of a parent (family context), that condition would likely both account for and compound the limited family resources, and also could affect family harmony because of the multiple stresses on the caregiver, adding another potential driver of separation.

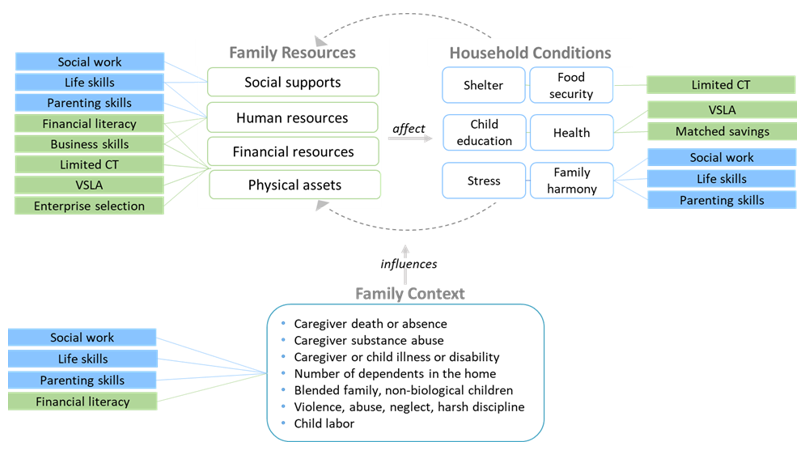

Once we had an idea about how different levels and types of drivers might be related and affect child separation, we attempted to demonstrate which specific HES activities might be most helpful to mitigate constraints or challenges in the family’s overall context. In Figure 3, we’ve slightly rearranged the concept map from Figure 2 and have added in blue boxes to indicate family support activities and green boxes to show economic strengthening activities that would be appropriate for improving resources or conditions.

Continuing the example above, for a household with a single adult caregiver facing issues with food security and child education for her family, financial literacy (management) skills might help stretch and prioritize existing financial assets, while a limited cash transfer (CT) could help stabilize food security and participating in a village savings and loan association (VSLA) could help over the longer term with educational expenses. Concurrently, life skills, parenting skills and/or social work support may be appropriate to improve relationships within the household while also increasing income earning potential and family harmony. Though this schematic is still very general, it helps to connect programmatic activities to household needs.

Making it useable

With the insights and evidence gained through the various information gathering and research efforts, we returned our attention to the objective of creating a useful and empirically-grounded resource guide to assist practitioners and planners in matching specific households with appropriate and effective HES activities. As we wrote in the guidance document, “HES [should] aim to address potential drivers of separation specific to the family, be monitored to assess progress or problems, and then be adjusted, if necessary (Laumann, 2016-2018). HES should also consider a family’s current economic activities, respond to a family’s economic vulnerability level and capacity, and help it move toward a sustainable livelihood that meets children’s basic needs, including education.” We were able, based on the various data collected, to describe in the guidance important elements of family characteristics, circumstances, capacities and context to be considered in the process, and how they might affect selection of HES activity. The guidance document also provides descriptions of common HES activities and their purpose, appropriate beneficiaries, the relevant evidence base and key considerations for implementation.

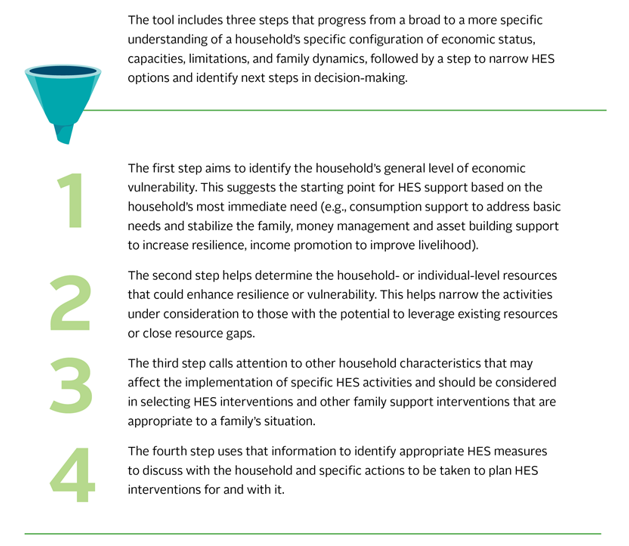

A final task was to pull all of this information together in a way that practitioners and planners could easily use to inform the integration of HES activities into case management planning. The result was the HES Activity Selection and Planning Tool (Figure 4). Each of the four steps summarized in Figure 4 is accompanied by a series of questions to help practitioners assess a household, along with tips on what types of HES activities may or may not be appropriate, given specific responses to those questions. While it is not as simple as a one-size-fits-all recommendation or a neat if-this-then-that decision tree, it facilitates discussion and consideration of the various strengths and limitations of a given family and the caregiver-child dynamics present in the home in a way that mirrors our conceptual understanding of the drivers of separation and their associated intervention points and activities.

The guidance and tool developed through the Family Care project were built on the various research activities – and related data sources – that came before them, and these research and evaluation activities added another layer to the evidentiary base to advance the field. Together, this work helps us better understand whether, which and when HES activities could be appropriately and effectively incorporated into family support programming, and we look forward to generating the next level of evidence on HES activities for family integration.

Photo caption: Forty-seven-year-old Maria Chateka from Chikwawa District, Malawi is a widow living with HIV currently looking after her son, her late sister’s daughter, and her grandchild. Through a Village Savings and Loans Group (VSL), she now owns a shop which brings her a healthy profit of $10 a day. She uses this money to pay for school fees, buy her household necessities, and reinvest into her VSL group.

Photo credit: © 2017 Nandi Bwanali/ONE COMMUNITY, Courtesy of Photoshare