The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for strong effective leadership during complex emergencies. There has been a lot of media coverage applauding the leadership of women during the pandemic, along with claims that U.S. states governed by women have better health outcomes than those led by men. Research comparing the leadership of men and women is not new. Some studies show that women are preferred as leaders during a time of poor company performance (Ryan et al., 2011). None of the previous research focuses on a crisis as complicated and severe as the current pandemic though – until now. In this post I discuss recently published research examining women’s leadership during COVID-19 in the United States and internationally.

Most of the previously published evidence on women’s leadership focuses on organizational leadership and monetary outcomes. In fact, Walsh et al. (2003) find only 2% of studies center on societal welfare outcomes, e.g., health and security. People perceive the leadership of women to fit during times of business downturn, so they are more likely to be selected for leadership positions at these times (Haslam and Ryan, 2008). This may be because women tend to be more empathetic than men (Toussaint and Webb, 2005), which in turn affects their communication styles. I observed this effect in a recent U.S. study, which I describe next.

Women’s leadership during COVID-19 in the United States

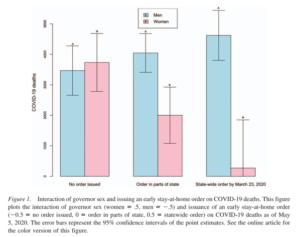

Figure 1: Interaction of governor sex and issuance of stay-at-home orders; Source: Figure 1 from Sergent and Stajkovic (2020)

The researchers attempt to explain this difference with a qualitative analysis of the pandemic briefings conducted by each governor between April 1 and May 5, 2020. They use theme dictionaries from applied psychology research to analyze the briefings with a focus on feelings and confidence. Based on the criteria given by the dictionaries, the authors find women governors expressed more empathy and awareness for the feelings of their constituents. Women governors also focused on work and money in their briefings, both major concerns for many people. Lastly, women governors displayed more confidence when addressing the public, which could explain why their stay-at-home orders turned out to be more effective in reducing deaths.

Women’s leadership during COVID-19 around the world

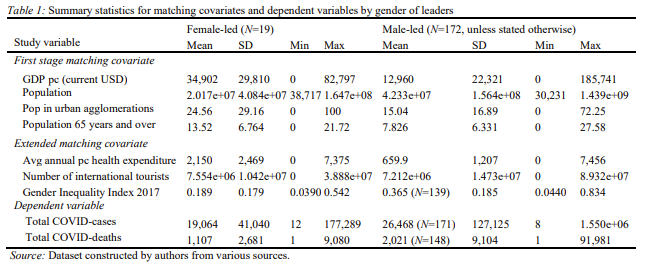

The results show there have been almost double the number of deaths in countries led by men (mean = 2,021) compared to countries led by women (mean = 1,107). Countries led by men also have a higher number of cases, but not as great of a difference compared to deaths. Figure 2 below presents the mean cases and deaths for countries along with summary statistics of the matching covariates.

Figure 2: Statistics for matching covariates and dependent variables by leader gender; Source: Table 1 from Garikipati and Kambhampati (2020)

Garikipati and Kambhampati also conduct an analysis where they remove countries from the sample that may have a disproportionate impact on the results – specifically, Germany, New Zealand and the U.S. – to test the robustness of their results. Removing these countries strengthens the connection between women leaders and a lower number of COVID-19 cases and deaths.

The authors use the same matching method described above to also conduct a policy analysis to explore the timing of when women leaders instituted a national lockdown compared to men. The findings show when compared to men, women leaders implemented a lockdown while the number of reported deaths in their countries was still low. The authors hypothesize that this response can explain the difference in the number of deaths at the beginning of the pandemic (the time period analyzed in the article). There is no difference in case numbers at the time of lockdown. Based on this analysis, women leaders responded quicker and more decisively regarding the implementation of national lockdowns.

What I’m left wondering

After reading (and now writing about) these two studies, I’m left wondering about a few things.

First, I wonder about the accuracy of the data on COVID-19 deaths. U.S. states or countries may have different criteria for reporting a COVID-19-related death, which can affect the comparison between them. The international study uses data through May 19, 2020, but does not give a starting point for the dataset. This starting point can vary greatly across countries. I suspect a lot of future research will aim to answer the question: when did the pandemic officially start.

Third, the timing of lockdowns and other mitigation policies is an aspect of these studies that I think can be looked at on their own, regardless of gender. Such research would provide us with findings on leadership during public health emergencies, in terms of gender as well as other factors. For example, the U.S. study examines several covariates in relation to COVID-19 deaths. Mask mandates and ventilator-sharing programs are both statistically significant in relation to deaths, but the researchers did not include governor sex in the analysis as they did with timing of a lockdown.

Finally, the qualitative aspect of the U.S. study (the analysis of public briefings) can be useful when leaders are deciding how to address the public during a crisis. I am curious to know if these trends continued throughout the pandemic and how it might affect the leadership style of men in the future. There will certainly be many studies conducted after this pandemic and leadership style should certainly be one of the focal points.

Photo credit: Corbis-VCG/Getty