Public health decision makers need accurate information about which interventions will be most effective within their given context. The evidence-to-practice gap in public health is well documented however (and described in this previous post). In this post, we propose that there are methodical procedures, or research utilization methods, that can and should be applied to support a systematic approach to facilitate the uptake of evidence in practice. Research utilization methods can support identification of evidence gaps, produce practice-based evidence, demonstrate efficacy, support dissemination to improve awareness, and facilitate intervention adaptations and adoption.

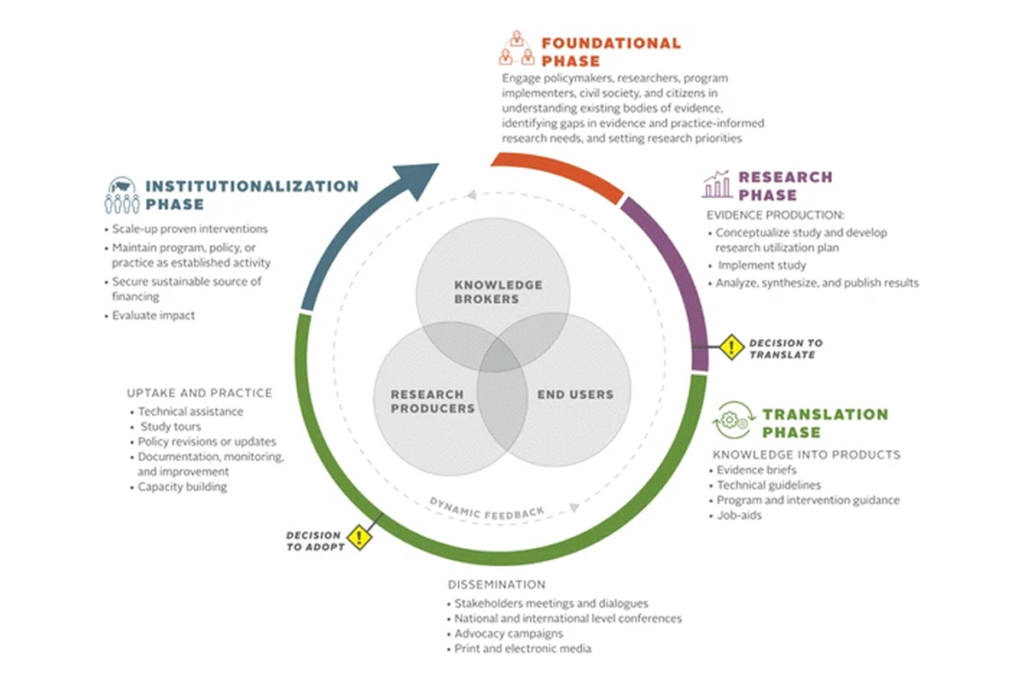

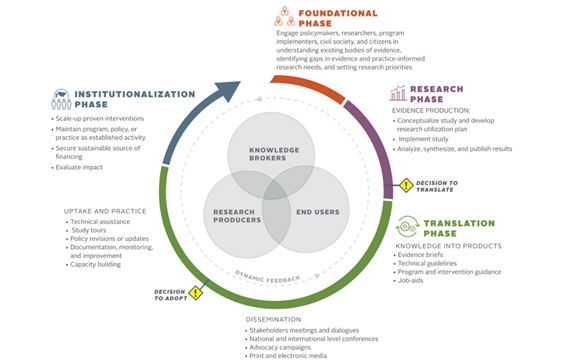

Our colleagues Christine Kim et al. (2018) used decades of experience to develop a four-phase research utilization framework “to guide global health and development efforts that seek to apply evidence to policies and programs” (p. 1). As we move across the phases in this framework in our own work, we are continually reminded that just as research requires systematic procedures, so does research utilization. We find, however, that the science behind research utilization is not well understood by those outside of the field and that within the field of research utilization we do not do a great job of documenting and sharing the methods we are using. Here we present the framework from the original Kim et al. article and also share applied methods relevant for each stage.

It is important to note that the process of research utilization is cyclical, and many of the methods that are listed for a particular stage can also support others. The summaries below are by no means exhaustive; rather they are illustrative of the various methodologies that can support the research utilization science.

Figure 1: Research utilization framework; Source: Christine Kim et al. (2018)

Foundational phase

Understanding the existing body of evidence to determine the best practices to address a particular health disparity, as well as the implementation and impact of those practices across contexts and populations, is key to ensuring evidence-based public health. As stated by Greene and Glasgow (2006), “If we want more evidence-based practice, we need more practice-based evidence.”

We find these research utilization methods relevant to the foundational phase.

- Literature review: Literature reviews provide a systematic approach for summarizing evidence to support decision makers with planning programs and prioritizing funding (Brownson et al., 2018). There are a multitude of literature review methods to utilize such as a systematic review, scoping review, realist review, systematic review of reviews (umbrella review), meta-analysis and narrative review.

- Ex-ante policy analysis: An ex-ante policy analysis prior to implementation offers an examination of potential policy alternatives, their impact and the implementation process. Methods often only include a retrospective or comparative analysis to understand policy approaches (Patton et al., 2016). Results from an ex-ante (before) analysis supports decision makers with identifying the most appropriate and informed intervention option for their context.

- Collection of practice-based evidence: Traditional sources of evidence, such as formal research and published, peer-reviewed manuscripts, often fail to capture the experiential knowledge of those implementing public health interventions in real-world settings. As such, the use of practice-based evidence to inform evidence-based practice is increasingly important (Green and Glasgow, 2006). Methods to collect practice-based evidence typically include community-based participatory research approaches and participatory systems science methods (Ammerman et al., 2014). The application of approaches such as whole-system-in-the-room, while less rigorous, have successfully elucidated this type of evidence and its value.

Research phase

One major contributor to the persistence of public health’s challenges as described by Glasgow and colleagues (2003) is “the assumption that effectiveness… naturally and logically follows from successful efficacy research.” And Martin et al. (2016) show us intervention efficacy testing often includes procedures such as randomization and intervention manipulation, that do not occur in real-world settings. Thus, the impact of interventions brought to scale outside of a study context may be minimized, if not negated.

We find these research utilization methods relevant to the research phase.

- Process evaluation: Moore et al. (2014) describe a growing recognition for process evaluation to inform intervention adaptation and scale-up. Process evaluations examine the quality and quantity of intervention activities, as well as why specific components were (or were not) implemented. Implementation tracking is one approach to support process evaluation; our colleagues at FHI 360 developed a novel intervention tracking tool to document implementation during the research phase.

- Costing study: A basic cost analysis involves the collection of information about the various resources needed to implement or replicate an intervention. This information informs future cost-benefit or cost-effectiveness analysis. The results of costing studies are extremely valuable to decision makers in resource-limited settings as they prioritize investments in approaches to address the public’s health.

Translation phase

Institutionalization phase

We find these research utilization methods relevant to the institutionalization phase.

- Acceptability assessment: An acceptability assessment helps identify whether an evidence-based intervention is appropriate for adaptation and scale-up in a new context; and if so, what potential adaptations are needed to ensure it remains effective within that new context (Ayala and Elder, 2011). Qualitative methods such as focus group discussions and interviews are often utilized to collect evidence of acceptability.

- Situation analysis: The World Health Organization (WHO) defines a situation analysis as “an assessment of the current health situation … [that] is fundamental to designing and updating national policies, strategies and plans” (WHO, 2016). A situation analysis explores the full system in which an intervention will be implemented and includes an assessment of the current health challenges and determinants of health, demand for services, health system capacity and performance, existing resources, and stakeholder positions (WHO, 2016). A situation analysis helps elucidate evidence about the feasibility of and readiness of a health system to successfully support implementation of an evidence-based intervention.

- Participatory action research (PAR) and community-based participatory research (CBPR): Wallerstein and Duran (2010) say participatory research methods “create space for postcolonial and hybrid knowledge, including culturally supported interventions, indigenous theories and community advocacy.” During the institutionalization phase, Ammerman et al. (2014) show participatory methods provide unique insight into community needs and provide an approach through which to engage a variety of stakeholders to gather input on how evidence-based practices can best be adopted, brought to scale and maintained in a current context.

- Case study research: Case study research seeks to capture information about how, what and why a particular phenomenon occurs and collects evidence that informs future adaptations and scale-up activities (Yin, 2009).

- Ex-post policy analysis: An ex-post policy analysis involves the evaluation of a policy once implemented. The analysis includes policy monitoring and the examination of factors such as actual versus planned performance, cost benefit and cost effectiveness, and policy revisions (Patton et al., 2016). The type of information collected via ex-post policy analyses informs future work at the start of a new research utilization cycle.

In the comments below, please share with us examples of how you have used the approaches we present in this article as well as other relevant methods for each phase of the cycle!

Photo caption: Research utilization framework

Photo credit: Christine Kim et al. (2018)