The findings from the Evidence for Contraceptive Options and HIV Outcomes (ECHO) trial have dominated headlines in global health spheres since their publication last month. Initially, the online conversation focused on the trial’s primary results, but lately, the Twittersphere has been buzzing about what comes next. Here I briefly recap the ECHO trial’s history and results, and then share what global health stakeholders are saying now that we know the findings.

What is the ECHO trial?

The question has swirled for decades whether intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA-IM), frequently marketed as Depo Provera, increases risk of HIV acquisition. This birth control method is very popular and widely used throughout sub-Saharan Africa. The cause for concern came from observational studies showing a correlation between DMPA use and HIV. Based on these studies, in 2017 the World Health Organization (WHO) downgraded DMPA from category 1 to category 2, meaning WHO advised that women should not be denied access to this contraceptive method, but they should be cautioned about the possible risk. As recently as May 2019, commentators argued that governments might want to consider subsidizing birth control methods “that do not come with the same risk” as Depo Provera.

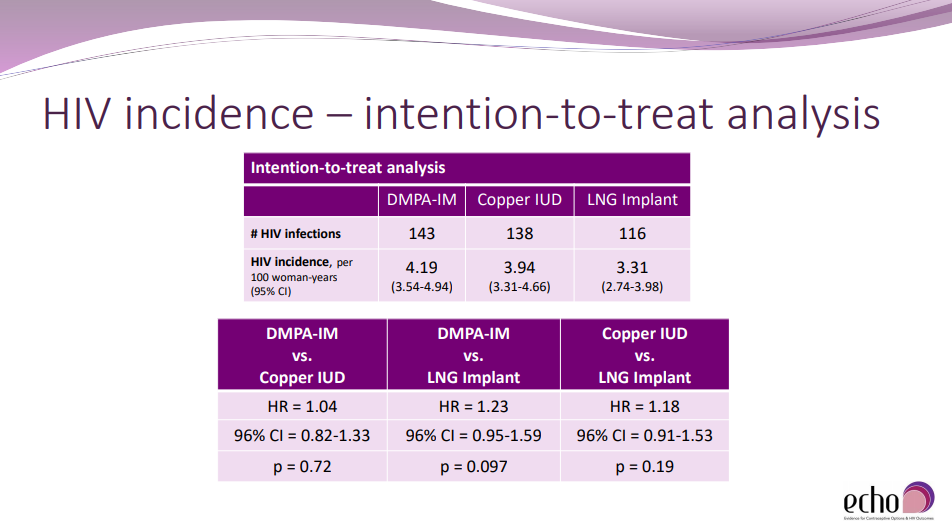

To address this question, a consortium of researchers led by FHI 360, the University of Washington, Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute (Wits RHI), WHO, and others, conducted a randomized trial from December 2015 through October 2018. The team designed the trial to compare HIV incidence among African women randomized to three different birth control methods: Depo Provera, a copper intrauterine device (IUD), and a levonorgestrel (LNG) implant, known as Jadelle. A randomized trial allows us to test whether DMPA causes higher risk of HIV acquisition rather than just whether it is correlated with increased HIV risk. Other study questions included rates of pregnancy, discontinuation of birth control method, and adverse events across the three methods. 7,829 women across 12 sites in eSwatini, Kenya, South Africa and Zambia participated in the study.

In designing the trial, the team selected the sample size – the number of women they needed to enroll in the trial – to allow them to detect a statistically significant 50% higher hazard of HIV comparing each method to each of the others. That simply means they enrolled enough women so that they could test statistically whether one birth control method increases the chances of acquiring HIV by 50% or more than any of the others. The researchers noted in their results presentation that they chose a 50% increase in HIV risk “based on formative work with stakeholders to determine a meaningful difference that would inform policy change.”

What are the ECHO trial results?

So, did the ECHO trial answer the big question? Yes. The trial results show no statistically significant (at the 5.0% level) difference in the acquisition of HIV between any pair of the three birth control methods. A woman considering these three methods can expect that her chance of acquiring HIV is not greater for any one method over another by more than 50%. You can see three comparisons in the slide below and you can read the full paper here.

Additionally, the ECHO trial findings confirm all three birth control methods effectively prevented pregnancy and show that a small percentage of women discontinued their assigned contraceptive method due to adverse effects. African women have long been provided Depo Provera, sometimes as their only contraceptive choice. The ECHO trial demonstrates that women do find other methods acceptable and continue using them as prescribed.

That’s all good news. The bad news is that the ECHO trial found a high rate of HIV incidence across all three groups of women enrolled in the study. The overall rate of new infections per year was 3.81% – that’s almost 1 in every 25 women. Addressing this high HIV incidence now dominates a great deal of the ECHO trial conversation.

What’s the global health community saying about the ECHO trial?

A commentary by Noguchi and Simelela published alongside the full results notes that while some questions about interactions between contraception and HIV have been answered, there is still an “unfinished agenda”. This agenda includes, for example, addressing HIV risk among the full range of contraceptive methods – like other injectable or oral contraceptives – that couldn’t practically be included in the ECHO study. The authors also raise questions about contraceptive access and delivery. For example, will WHO now revert Depo Provera-type contraceptives to a medical eligibility criteria category 1 (no restrictions) as it was prior to 2017? The authors say addressing this unfinished agenda comprehensively can help combat the high rates of HIV incidence highlighted in the ECHO results.

Other global health stakeholders agree. Since I tweet for @fhi360research, I see these conversations continually pop up in our feed. Here are a few samples.

The ECHO results confirm HIV rates remain unacceptably high in the study area despite prevention efforts. Organizations and individuals are demanding action such as improved access to the full range of contraceptives and the integration of HIV and family planning programming.

ECHO found no substantial difference in HIV risk among women using the 3 contraceptive methods, but data sound alarm about rates of HIV–almost 4 percent. Underscores urgent need to integrate HIV & sexual and reproductive health programs. #ECHOStudy #SRHR https://t.co/zYRdCVvRZY pic.twitter.com/vIaBjxA1Va

— AVAC (@HIVpxresearch) June 13, 2019

#HIVacquisition amg #ECHOtrial participants was high despite given condoms & being counseled on safe sex. What does it say about #effectiveness of these interventions? What else is needed? #EchoStudy @FP2020Global @Pop_Council https://t.co/LgKyH9HoSj via @nytimes

— Anrudh Jain (@AnrudhJain) June 27, 2019

Our CEO @QuamLois on #ECHOStudyResults @TheLancet, This is an important development for women globally and confirms that women & girls should have access to a range of options for contraception along with high-quality counselling." Full statement > https://t.co/p791O8Wx40

— Pathfinder Int. (@PathfinderInt) June 14, 2019

Following @TheLancet #ECHOtrial results, #HIV prevention must be fully integrated into #FamilyPlanning programs and women's autonomy to choose the best method for themselves, free of stigma and discrimination, should be respected: https://t.co/pPPwyaWEZJ

— MSH (@MSHHealthImpact) June 25, 2019

Following a recent WHO-convened meeting in Lusaka about the ECHO trial results, activists agreed that access to family planning and HIV prevention methods – including preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) – must be improved.

We seek for everyone to commit to equity in access to most current contraceptives & #HIV prevention methods, moving beyond status quo, doing business unusual, & substantively responding to #ECHOTrial results by actively scaling up access to & diversity in method mix.

— ATHENA (@NetworkAthena) July 10, 2019

@lmworeko ‘Too many #HIV infections’ What does it take to remind us we are talking about human beings, young women? If #PrEP is good enough for #keypopulations – when will it be good enough for my daughter? Let’s put #PrEP on table for #AGYW. #ECHOTrial results demand we do more.

— ATHENA (@NetworkAthena) July 10, 2019

Many stakeholders fear what may come next and some have issued a call to action asking funders to invest further in HIV prevention.

Yvette Raphael @pozcandy worked on study as an external civil society advisor: My greatest fear is that the results are taken as a sign that nothing needs to change for the women and girls that I spoke and worked with while I was on the road. #ECHOtrial https://t.co/fp9VB49fvc

— The Aurum Institute (@Auruminstitute) June 13, 2019

Call to action: @lmworeko challenged all to make a US$50M match that was invested in #ECHOTRIAL to be invested in implementing the trail results @WHO @ICWEastAfrica @UNFPA @NetworkAthena @HIVpxresearch @BillGates @UNAIDS @PEPFAR @UN_Women @GlobalFund @Aidsfonds_intl

— ICWEA (@ICWEastAfrica) July 10, 2019

Time to act on evidence and put funds to work on lessons from #ECHOTrial https://t.co/894Cu2GHra

— Aditi Sharma (@aditi_campaigns) July 10, 2019

We need a 50M USD match for implementing #ECHOTrial results to prevent new HIV infections in AGYW. Join the campaign if you care about them. @FP2020Global @lmworeko @UNAIDS @ippf @UN4Youth @HIVpxresearch @gatesfoundation @RCNFoundation @BMKGiftSnr1 @FacyAzizuyo @ICWEastAfrica

— Margaret Happy (@Margaret2Happy) July 11, 2019

The ECHO study team plans to publish a dozen or more manuscripts using the trial data. I expect the conversation around the ECHO results to continue for months or years to come. If you want to follow along, start with the #ECHOtrial hashtag on Twitter. The trial answered many questions, but the global health community is still learning and fine tuning how we get to zero HIV infections.

Photo credit: FHI 360