A new PLOS ONE article on tuberculosis (TB) co-authored by an FHI 360 colleague in Ethiopia recently caught my attention because of its global health implications. The article focuses on isoniazid preventive therapy – IPT or simply isoniazid, a lifesaving treatment used among people living with HIV (PLHIV) to prevent TB. Isoniazid is especially helpful at preventing TB after the initiation of HIV antiretroviral therapy which is a period when TB risk is high (Yirdaw, et al., 2014). Since TB is the deadliest infection for PLHIV (WHO, 2018), WHO recommends taking isoniazid during this initiation period (WHO, 2011). Isoniazid lowers the risk of mortality, treats latent (non-symptomatic) TB infections, and slows the progression of TB in PLHIV (Golub, et al., 2009; Volmink and Woldehanna, 2004).

Sometimes PLHIV still develop TB while taking isoniazid, which is defined as “breakthrough TB”. Studies that determine how common breakthrough TB among PLHIV actually is and what factors influence its development can better inform health care providers and policymakers as well as provide additional evidence to support test-and-treat strategies. In this post, I summarize how the new PLOS ONE article accomplishes both.

Together with researchers from Addis Ababa University, MERQ Consultancy and the Gates Foundation, FHI 360’s Kesetebirhan Delele Yirdaw conducted a retrospective longitudinal study spanning 2005 through 2014 to calculate the magnitude of breakthrough TB (and use of isoniazid) and assess the factors associated with its development. The team analyzed data from existing records of all newly enrolled patients (n = 35,789) in HIV care across 11 randomly identified government hospitals in three different regions in Ethiopia.

Calculating the magnitude of breakthrough TB

Yirdaw, et al. first calculate the uptake of isoniazid. Overall, the global uptake of isoniazid among PLHIV has been slow but there has been progress – growing from 5 percent coverage in 2013 (WHO, 2014) to 52 percent in 2016 (WHO, 2017).

Using MS Access to clean and store data and STATA to analyze it, the authors find 4,484 of the 35,789 PLHIV received isoniazid. That’s only 12.5 percent in this study area.

Isoniazid coverage gaps exist for many reasons – pill burden, side effects or overlapping side effects with HIV antiretroviral medications. However, a separate important factor is noted in the article: health care providers. The authors point out that providers may fear drug resistance and limit isoniazid initiation. But can PLHIV who develop TB while taking isoniazid lead to drug resistance? A systematic review conducted by Balcells, et al. (2006) says no and this should reassure providers that isoniazid is safe.

Second, the researchers determine the incidence of TB.

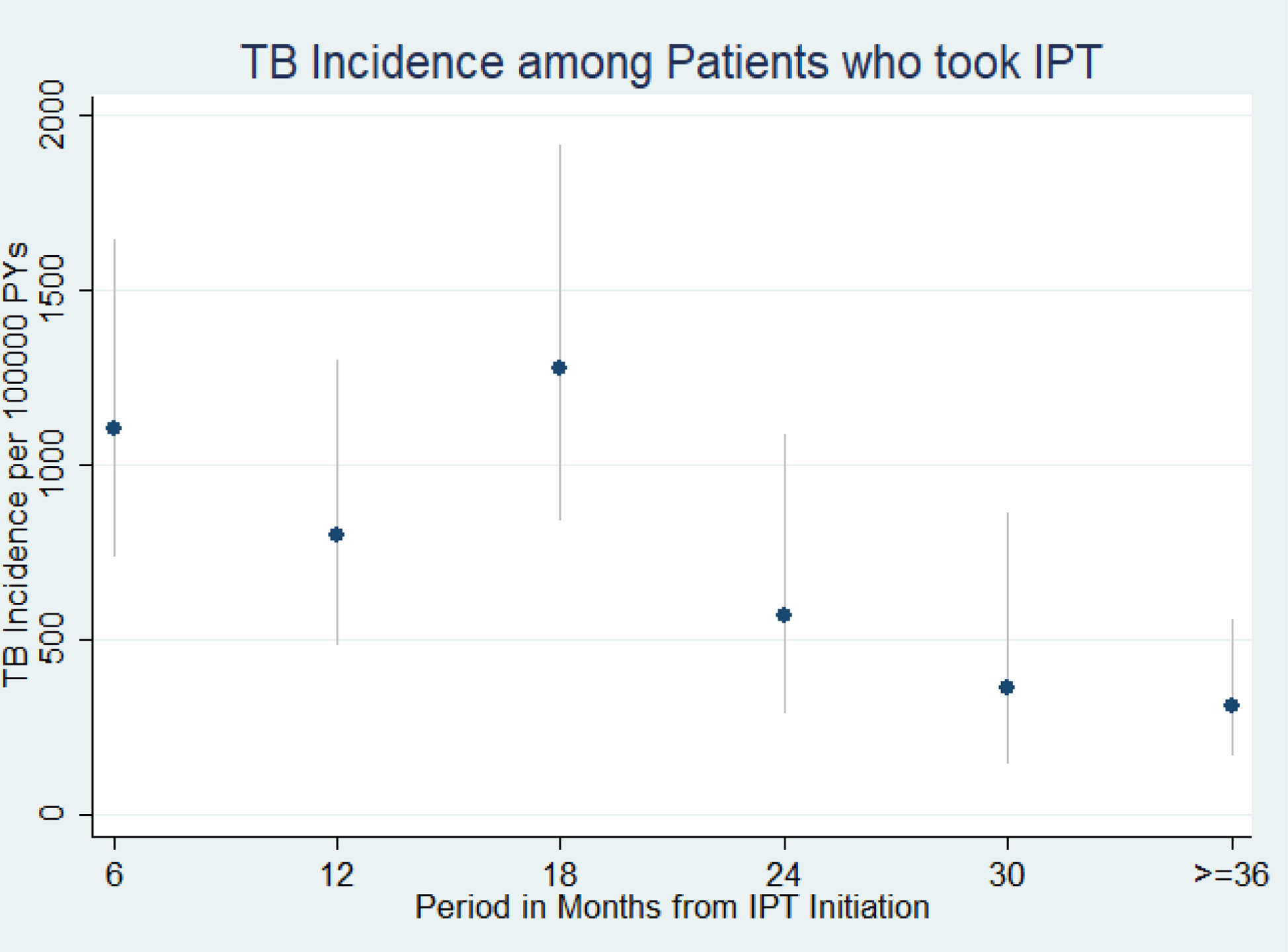

Of the 4,484 PLHIV receiving isoniazid, 88 (or 2 percent) still eventually developed TB. This diagnosis appears mostly in the first 18 months after initiating isoniazid, as shown below in the figure pulled from the article.

Figure 1: TB Incidence among patients who took isoniazid preventive therapy in Ethiopia, September 2005 to October 2013 (n = 4,484). Source: PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211688

Of the 88 PLHIV who developed TB, only 24 received a TB diagnosis while taking isoniazid – aka breakthrough TB. Notably, 7 of the 24 received a TB diagnosis within the first month of isoniazid initiation. The authors acknowledge this first-month jump may represent undiagnosed cases missed because of a “failure to properly adhere” to WHO’s TB screening algorithm or the use of traditional TB diagnostics (instead of new rapid diagnostics methods like the GeneXpert).

As a result, the authors call breakthrough TB “uncommon” in this study area.

Assessing factors associated with the development of breakthrough TB

Yirdaw, et al. also identified demographic and clinical variables associated with the development of breakthrough TB. The authors used Cox regression analysis to examine age, gender, WHO-defined HIV stage, CD4 count, HIV antiretroviral medication status, and duration of HIV antiretroviral medication status.

Their analysis shows only two factors influenced the development of breakthrough TB: CD4 count and HIV antiretroviral medication status. PLHIV with higher baseline CD4 counts and adherence to HIV antiretroviral medications experienced lower levels of breakthrough TB. No other variables influenced the occurrence of TB in PLHIV while taking isoniazid.

What are my takeaways?

The article highlights several takeaways for those interested in global health. Check out the full article to read them all. Here are two takeaways that I personally found the most compelling.

First, the authors find that breakthrough TB is uncommon in the study area. The uptake of isoniazid is low overall, but so is the magnitude of breakthrough TB among PLHIV taking isoniazid. Other studies cited by the authors confirm isoniazid’s effectiveness among PLHIV in high-income countries (Sterling, et al., 2011) and in another Ethiopia study (Yirdaw, 2014).

Second, the global health community has long pushed test-and-treat strategies for HIV and TB regardless of certain variables like CD4 count. Yirdaw, et al. confirm test-and-treat can be especially successful for PLHIV with high CD4 counts. The authors show only high CD4 counts (and adherence to HIV antiretroviral medications) stopped breakthrough TB.

New evidence like the study presented above continues to shape our understanding of TB, HIV, and the many ways they are interconnected. Overlooking vital preventative treatments like isoniazid can stop us from eliminating either epidemic. Let’s continue to publish work that can improve treatment outcomes and better inform decision makers to achieve that goal.

Photo caption: A patient receives tuberculosis treatment from a health worker

Photo credit:© 2011 Arturo Sanabria, Courtesy of Photoshare