When I worked in Ethiopia, many people in my community asked some version of “why aren’t you married?” I quickly settled on my response, “I am not finished with school, and my parents agree I must finish my education first.” Their typical reply was “oh, yes, of course.” I was never sure if it was a nod of understanding or a nod of sympathy, but it usually ended the conversation.

Now that I have completed my master’s degree, I fill my days reviewing newly published literature and attending research seminars. Recently, I came across a study on early marriage and education. The title alone – Students and brides: A qualitative analysis of the relationship between girls’ education and early marriage in Ethiopia and India – got me to pick up the paper; however, the subject matter kept me reading. Part of the article focuses on a topic not often discussed – early-married women and the social norms that influence whether they continue their education. Plus, I am eager to learn more about qualitative methods. Here I share more about the article and some of the things I learned.

Setting the scene

Having lived in Oromia, I was surprised to see the combination of Oromia and Jharkhand. How could these two places be similar? It turns out, Oromia and Jharkhand are quite similar. They have similarly sized populations, a similar ratio of rural and urban populations, and a similar median marriage age – 18.2 and 19 years old, respectively.

The authors drew from two existing early marriage interventions: the Oromia Development Association’s Comprehensive Adolescent/Youth Sexual and Reproductive Health Project (ODA) and the Regional Initiative for Sexual Health for Today’s Adolescents (RISHTA) Project in Jharkhand. The interventions had similar aims with slightly different implementation. ODA, which started in 1993, is school-based and implemented by teachers. RISHTA, which started in 2001, is community-based and implemented by trained youth leaders.

Methods

The authors determined participant eligibility as females who received the intervention and either a) married prior to the age of 18, or b) were able to cancel or delay a marriage until age 18 or later. Once identified, each girl selected up to three marital decision makers (e.g., parents, in-laws, teachers, etc.) to participate in interviews. The sample of participating females is limited to only those girls exposed to the early marriage prevention programs and, as such, Raj, et al. note their findings may not be generalizable outside of Oromia and Jharkhand.

In Oromia, the authors recruited participants from a sampling frame of 124 primary schools in two of eight ODA districts. In Jharkhand, the sampling frame included 32 villages in Saraikela Kharsawan district. Each interview was semi-structured, audio recorded in a private setting, and lasted for 45 minutes. The authors cut 58 interviews from the sample (mostly from Oromia) for reasons like poor sound quality or eligibility. Despite these data collection challenges in Oromia, Raj, et al. conclude the final sample is comparable across groups. The final analysis includes 207 interviews: 44 girls and 62 marital decision makers from Oromia and 49 girls and 52 marital decision makers from Jharkhand.

Using content analysis, the authors develop a coding structure with themes and sub-themes corresponding to the interview questions. I was not previously familiar with this method and I needed to learn more. I Googled latent content analysis and found this helpful article on content analysis in a qualitative study.

For additional details on the study procedures, previous analysis and coding process, Raj, et al. indicate more information can be found in this article and in these briefs: Ethiopia and India.

What themes did the authors find?

Raj, et al. identify three major themes: 1) benefits and disadvantages of girls’ education, 2) enablers and barriers to continuation/completion of secondary education, and 3) enablers and barriers to education post-marriage.

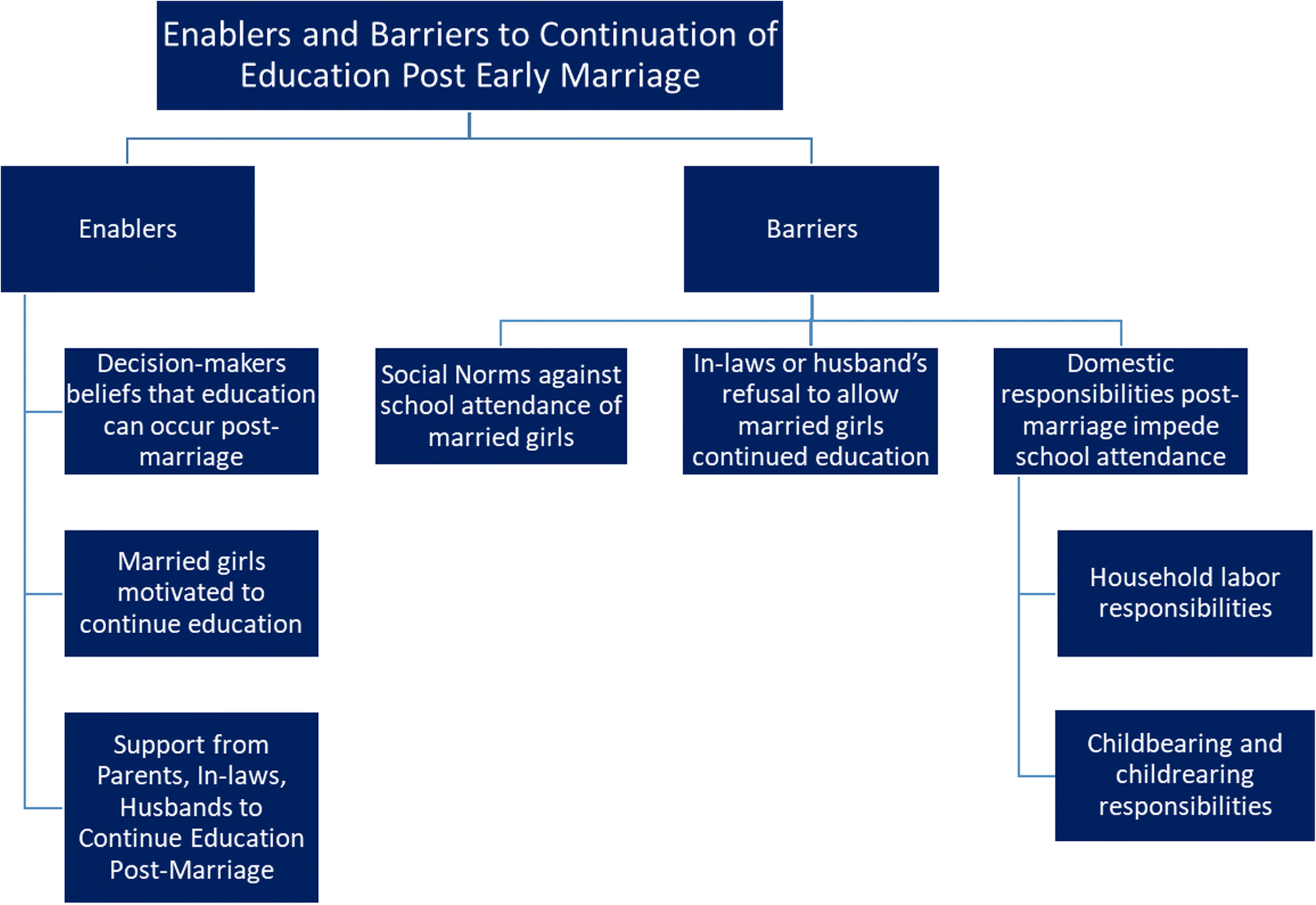

Now, I want to take a moment to focus on the third theme (enablers and barriers to education post-marriage) because, even given my made-up “why aren’t you married” answer in Ethiopia, I knew marriage was in no way a barrier to my education. However, I also knew that my experience was not the same for the girls and women I worked with, so I wanted to learn more about their enablers and barriers. Those are detailed in the below figure pulled from the article. Notice the attitudes of in-laws and husbands about whether to continue education post-marriage are both an enabler and a barrier.

Figure 1: Enablers and barriers to continuation of girls’ education post-marriage; Source: BMC Public Health, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6340-6

The geographic differences are not apparent in the article’s flow charts. According to the authors, the belief among decision makers that education can continue post-marriage is more common in Oromia, while the self-motivation of married girls to continue education is more common in Jharkhand. Participants from both groups describe the impacts of physical barriers like domestic responsibilities post-marriage (i.e., household labor and childbearing/childrearing responsibilities) on their ability to continue school.

A better understanding of enablers and barriers to girls’ education

The authors note several findings about the perceptions of girls’ education and early marriage across the study’s three themes in both countries. Many study participants recognized the value of girls’ education (e.g., builds life skills, provides better career opportunities, improves household management, etc.). However, this recognition did not override the concerns and stigmas around societal gender norms that devalue girls’ education and reinforce a “girl’s value based on her marriageability.” In addition, compared to participants from Jharkhand, participants in Oromia highlighted financial barriers and detailed abuse and harassment as girls walk to and from school.

Overall, according to the authors, one reoccurring factor for whether a girl continues her education is apparent: a girl’s own self-belief in the importance of her education pre- or post-marriage. The girl has a greater chance of staying in school when this self-belief is coupled with the support of the marital decision makers. Known as self-efficacy, this self-belief shows up in participant responses in decisions to delay marriage or return to school after marriage.

What I learned about girls’ education and early marriage

Two things stick with me after reading Raj, et al.’s article. First, the identified themes point to the fact that education is more than the count of the number of children in school. Counts are important, but they are only one part of the answer to improving girls’ access to education. Understanding the context around keeping girls in school and not just how many girls are in school better informs my understanding when researching education programs going forward.

Second, the findings suggest if a girl is perceived as not being good at school, it is harder for her to stay in school. The authors state that this perception can negatively impact the willingness of parents to provide financial support for attending school or lead to a girl deciding she wants to marry instead of continuing her education. I interpret this as compounding poor school performance. It seals the impression that she is not good at school and that impression can stay with her for the rest of her life.

Let that sit with you for a moment. The rest of her life. Before reading this article, I knew girls around the world must often choose between education and marriage. But to know is one thing, to see it in print is another. As I re-read through all the participant quotes, the choice (or lack of choice) faced by each girl now lands with a little more force.

Photo caption: In India, a young tribal bride wearing a headband of bank notes indicating her family’s property rides on the shoulders of her brother and other celebrating villagers.

Photo credit: © 2016 Arvind Jodha/UNFPA, Courtesy of Photoshare