Introduction

I had the opportunity to attend the Global Evidence Summit (GES) in Prague, Czechia (10 – 13 September 2024). The GES is largely about systematic evidence reviews, meta-analyses, and guideline development; previous GES conferences centered on evidence networks and evidence in a post-truth world. A main theme throughout the conference this year was the potential to harness AI in evidence synthesis and meta-analysis. It was inspiring to see many new and innovative examples of these technologies transforming how researchers approach their work; it was equally encouraging to see numerous examples of failures, demonstrating the need for ongoing exploration and high potential for breakthroughs. Yet, there was also a sense of trepidation, as the capabilities and reliability of AI are not widely understood.

In this post, I highlight evidence and speeches from the GES to argue that researchers need to explore the use of AI for evidence synthesis, and I suggest practical expectations and boundaries. This includes both the use of machine learning models and new, generative artificial intelligence. First, I discuss the ethical imperative that researchers must experiment with and explore this new technology. Then, I encourage us to think bigger and expand our scope. Recognizing AI is not perfect, I also suggest some guardrails to using AI safely. Lastly, I highlight possible changes to the workplace to help create an AI-enabling research environment.

We have an ethical imperative to explore and experiment with AI

The most memorable session was a structured, banter-filled debate between experts in the use of AI in evidence synthesis. The debate posed the question: “does AI have the potential to replace humans in evidence synthesis.” The affirmative team pointed out the time required to produce a systematic review, and how outdated reviews pose an ethical risk. “Almost 1 in 4 reviews that are not updated within 2 years of original publishing will contain conclusions inconsistent with new medical knowledge”, opened Amir Qaseem, Vice President of Clinical Policy and the Center for Evidence Reviews at the American College of Physicians. With the exponentially growing volume of scientific literature published every year, the long periods of time the traditional review process takes to produce knowledge can pose an ethical risk of leaving critical research unread or under-utilized. Demonstrating this challenge, in one session, Dr Honghao Lai of Lanzhou University found that Claude-2, a generative LLM from Anthropic, was able to complete a risk of bias assessment of 30 RCT articles, double reviewing each article, with a mean duration of 53 seconds. Without generative AI, the same task would take two separate individuals orders of magnitude more time, thus limiting the potential scope or timeliness of their work.

In addition to AI supporting the synthesis of evidence, it can also contribute to keeping research up to date. There is a growing number of retracted studies. Isabelle Boutron, director of Cochrane France, described a new product called “retractobot” that informs authors their manuscripts reference retracted studies; in 2023 it identified and contacted over 100,000 researchers citing retracted studies.

We should not expect perfect results in our first attempts using AI, just as we do not expect new methods or innovations to succeed on the first try, but the field is developing quickly. As researchers we have an ethical imperative to consider the use of AI in our work, especially when, as Dr. Thomas explained, “the risk is that decision-makers will increasingly rely on less robust, AI-generated syntheses, because it can supply them answers when they need them, even if it is less accurate.”

Expand your scope: Think bigger

One presentation by Ms. Diana Danilenko on “A Living Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Effectiveness of Behavioural Interventions for Household Energy Savings” described using an ML-enhanced systematic review methodology to screen articles that continuously assess the efficacy of different interventions in reducing household energy demand and associated CO2 emissions. The use of ML allowed the authors to screen over 100,000 titles and abstracts, developing a statistical stopping criterion for prioritized title and abstract screening in living evidence applications, and resolving some of the statistical challenges in regularly updating network meta-analysis. Using new technologies, they were able to incorporate new research and update this analysis regularly with ease, something entirely impossible without AI. A promising opportunity of AI is the potential to expand our scope, think bigger, and imagine innovative ways to approach previously insurmountable challenges.

Use AI within your area of expertise

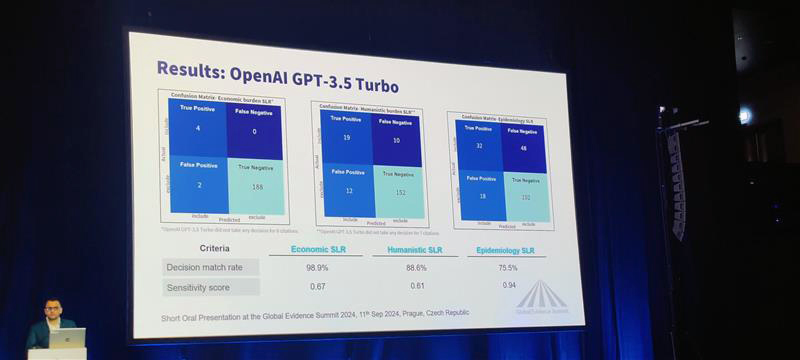

As researchers consider ways to utilize AI to expand or improve our work, it is important to rely on AI for tasks that we are comfortable overseeing and fact-checking. Multiple presenters delivered a series of rapid oral presentations on the impact of artificial intelligence in their work that demonstrated this point well. Mr. Hemant Rathi tested GPT 3.5 Turbo’s performance in primary screening three types of systematic reviews, and found that in some sectors GPT was “correct” 98.9% of the time, and in others as low as 75.5% of the time. Notably, however, “correct” was determined by comparing GPT to the final decision of 3 human reviewers; individual human reviewers can have an error rate of up to 10% in some fields.

Dr. Biljana Macura found that Google Gemini was better at excluding records at title/abstract review than humans, but had a 23% false negative rate in full text review. For articles that humans were more likely to include in title/abstract but later exclude at full text review, Gemini was more likely to exclude them in title/abstract.

One poster compared human versus AI’s performance mapping of published evidence syntheses to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and found concurrence between humans and AI only 52% of the time. Conversation with the authors explained that much of the disagreement came from critical interpretations of nebulous terms or differing taxonomies in publications that does not exactly match what’s written in the SDGs.

The debate mentioned previously asked “should AI replace humans in evidence synthesis”, and the audience weighed in: 58% of those attending voted “no”, and in conversations afterwards most cited the need for professional oversight of AI results. “Humans employ evidence and value-based judgements: consciously dealing with uncertainty, weighing conflicting results, and taking different perspectives. Gen AI is a statistical representation of reason, but not critical thought” explained Valentin III C. Dones of the Center for Health Research and Movement Science, University of Santo Tomas.

Researchers looking to explore the use of AI in their work should consider applications they would feel comfortable doing on their own, but are time-consuming, in-depth, or otherwise resource intensive. Ultimately, it is up to the researcher to review the results and assess for accuracy.

Creating an AI-enabling research environment

Start with off-the-shelf tools, says Tom Schofield, president of EBQ Consulting and research analyst at Los Angeles County. Many free or relatively affordable tools can easily scan large amounts of custom-curated text or data to draw insights or inferences. Following all data security and personally identifiable information protocols, researchers can start by simply opening any of the many online tools and seeing what happens.

As we begin to expand our use of AI, our teams and roles may have to shift to accommodate this “new AI team member.” Dr James Thomas describes six new roles for an AI-enabled research environment:

- Evidence synthesist: asks “which new tools can we use, and how?”

- Evidence methodologist: oversees research methodology, defines best practices, and evaluates tools’ performance

- AI development teams: aligns tools with practices and principles of research integrity, focusing on tool evaluation not marketing

- Organizational leadership: Sets and implements standards and policies for conducting and reporting AI-enabled evidence synthesis, and develops implementable standards

- Funders and commissioners: provides resources for evidence synthesis, and for technology development

- Publishers: Ensures that standards are implemented and protects the trustworthiness of publications

We should not be alarmed if our roles and tasks change as we begin to integrate AI into our work.

Conclusion

The debate on AI replacing humans for evidence synthesis was heated. For closing statement, Artur Nowak of Evidence Prime on the affirmative team approached the microphone and said, “rather than me delivering closing remarks, I will let AI speak for itself.” He placed the microphone over his laptop and let ChatGPT speak for five minutes for the affirmative. GPT concluded by confidently declaring: “AI will always continue to improve and stay up-to-date faster and better than humans; we must start with a collaborative human-AI model as a transition, and gradually reduce human workload over time.”