Introduction

We recently conducted, together with researchers Alexandria Mickler and Alice Cartwright, a systematic review of the scientific literature on the tried-and-tested ways in which menstrual changes have been measured.

A key tenant of science is to learn from multiple studies of the same questions and build a body of knowledge, which is enhanced when different studies use the same concepts and measures. For example, one study led by environmental scientists can focus on how pesticides may change menstrual cycles among farmers, while another study on the same topic led by public health scientists might measure those changes in a different way. When this happens, it can be difficult to compare data and gather evidence, even if it’s on the same topic. This inconsistency in how we

measure menstruation is incredibly problematic and unfortunately common in relation to menstrual research.

To explore this issue, with funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), we recently conducted, together with researchers Alexandria Mickler and Alice Cartwright, a systematic review of the scientific literature on the tried-and-tested ways in which menstrual changes have been measured across many different fields of research.

In this post we summarize the methods used in the systematic review, highlight key findings, and discuss the potential impacts these findings may have on future menstrual research and healthcare.

Methods

The final set of papers studied 94 different ways researchers have measured menstrual changes—everything from questionnaires to squeezing a bulb to measure intensity of pain.

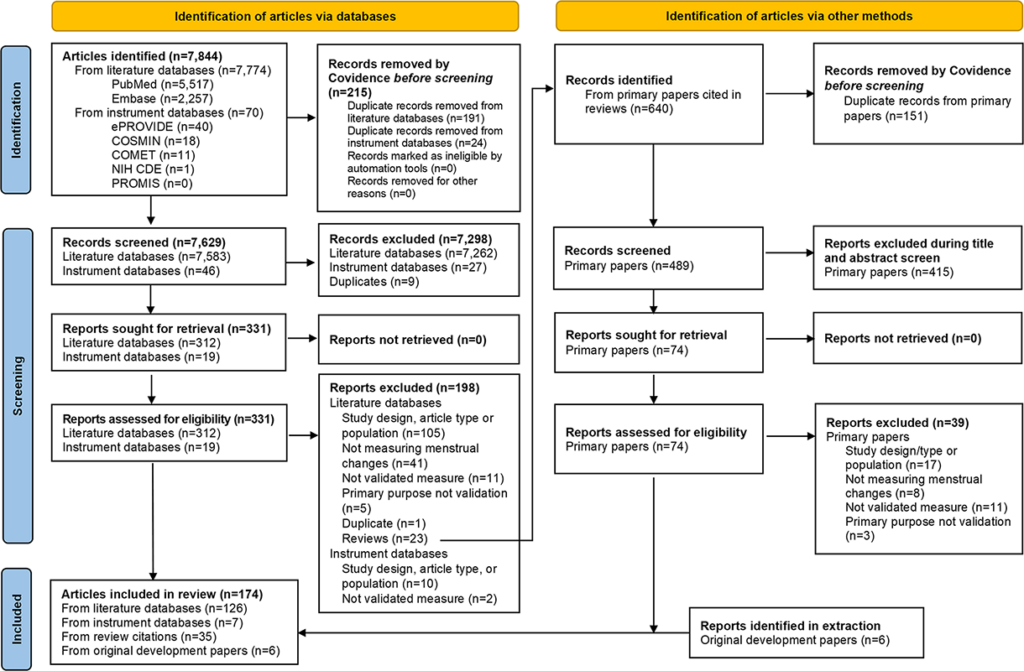

This systematic review began with scouring several different databases for scientific papers that mentioned anything about both menstruation and measurement. This research yielded over 7,000 scientific articles. Our team of five narrowed this down to 174 papers. We included review papers and articles with prospective, retrospective, or cross-sectional study designs, and only the ones that focused on validating the measurement of menstrual bleeding, blood, pain, or perceptions of menstrual changes. The final set of papers studied 94 different ways researchers have measured menstrual changes—everything from questionnaires to squeezing a bulb to measure intensity of pain. We then analyzed these measurement tools, recording which menstrual changes they measured and giving them each a score for measure quality and clinical trial utility based on the characteristics laid out in the table below.

Some instruments had many papers written about them, while others only had a few or just one, so a total evidence score was also calculated by totaling all scores across all attributes of measure quality and clinical trial utility.

| ATTRIBUTES USED TO ASSESS INSTRUMENTS MEASURING MENSTRUAL CHANGES |

Measure quality | • Conceptual/measurement model

• Reliability

• Content validity

• Construct validity responsiveness

• Sensitive nature of questions |

Clinical trial utility | • Interpretability of results

• The transferability of the instrument

• Participant burden

• Investigator burden |

Findings

Many of the tools did not have evidence about their abilities to detect changes over time, how well they could be used across different cultures and contexts, and how menstrual stigma could influence people’s willingness or comfort in providing correct information.

We found that 75% of tools were developed and studied among people in the U.S. or Western Europe, 43% were only available in English and most only measured one or two types of menstrual changes. Nearly 60% of instruments were developed for populations with menstrual or gynecologic disorders or symptoms (e.g., endometriosis or polycystic ovarian syndrome). We also found many of the tools did not have evidence about their abilities to detect changes over time, how well they could be used across different cultures and contexts, and how menstrual stigma could influence people’s willingness or comfort in providing correct information. Some of these tools were not developed in consultation with people who menstruate themselves and certain fields were particularly lacking in this area. Additionally, none of the tools were developed or studied with trans and nonbinary people who menstruate.

There are few examples of fields in which patient perspectives are leading the way — namely research on heavy menstrual bleeding and endometriosis — but for many, and specifically for those working in contraceptive research, these perspectives need to be better centered and used to inform research.

It is clear that researchers need significantly more resources to develop better and more standardized measurement tools.

In looking through thousands of papers and reviewing nearly 100 instruments, it is clear that researchers need significantly more resources to develop better and more standardized measurement tools. It is also clear that studies do not always consider the contexts, languages and complete experiences of people who menstruate. In short, we need to do better.

To address these gaps, FHI 360 is partnering with researchers in South Africa and the Dominican Republic on a four-year multiphase, multisite study to develop, refine and pretest a tool to measure menstrual changes for contraceptive clinical trials. During the first phase of this study, researchers will conduct focus group discussions with participants to gather insights into their experiences with menstrual changes caused by contraception. This information will be used to develop a new tool that will be tested with people who are starting new methods of contraception to measure menstrual changes over time.

Implications

We need more rigorous formative research — across sociocultural contexts — that is focused on how all people who menstruate experience and understand their menstrual cycles.

This type of study and the systematic review discussed above are just the first steps in a long process of ensuring people who menstruate are at the heart of and driving the menstrual health research that impacts them. We need more rigorous formative research — across sociocultural contexts — that is focused on how all people who menstruate experience and understand their menstrual cycles and that more fully addresses menstrual stigma. From that research, we can produce the evidence and information that can be used by individuals to inform their everyday health decisions.

In a future informed by this type of research, the ebbs and flows of menstruation may be a little easier to understand and manage: Patients might have the information to more clearly communicate with their health care providers when they experience changes in bleeding and pain caused by a cyst or endometriosis. They might be able to select a contraceptive method based on more precise and complete information about the menstrual changes they will experience—which might even include choosing a method that helps manage symptoms associated with a cyst or endometriosis. Not only that, but they might also have the language and information needed to productively discuss the changes they experience with their health care provider.

This research might also help break down menstrual shame and stigma as well as contribute to language shared among friends and family, supporting individuals in discussing experiences that can significantly impact their lives and connecting whole communities—across science and across generations.

The systematic review referenced here was made possible by a dedicated team of researchers, including the authors of this blog as well as Alexandria K. Mickler (Independent Consultant) and Alice F. Cartwright (Guttmacher Institute). The systematic review was funded through the Innovate FP project and is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this piece are the sole responsibility of FHI 360 and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Sharing is caring!