Introduction

Yet, to be relevant and effective, development policy must be informed both by scientific and professional knowledge and local knowledge. This shift is aligned with recent conversations about decolonizing global development, which have included debates about the sources of knowledge used in designing policies. In this blog post, I share findings about the role of local knowledge in informing development policy from four case studies in Indonesia, which indicate that incorporating local knowledge improves development policy formulation and implementation.

Study and Methods

We used a longitudinal design with qualitative methods to assess the roles of various forms of knowledge in policymaking and implementation in each case in 2016. To do so, we partnered with local NGOs who acted as intermediaries for their communities in each case. We conducted two follow-up data collections in 2019 and 2022, which included key-informant interviews with a total of 23 informants to examine both the case studies themselves as well as what happened–and did not happen–as they were implemented. In addition to the interviews, we conducted site visits to see implementation in action to triangulate our understanding.

We coded our data according to predetermined themes generated from the literature on evidence-informed policymaking.

Results and Discussion

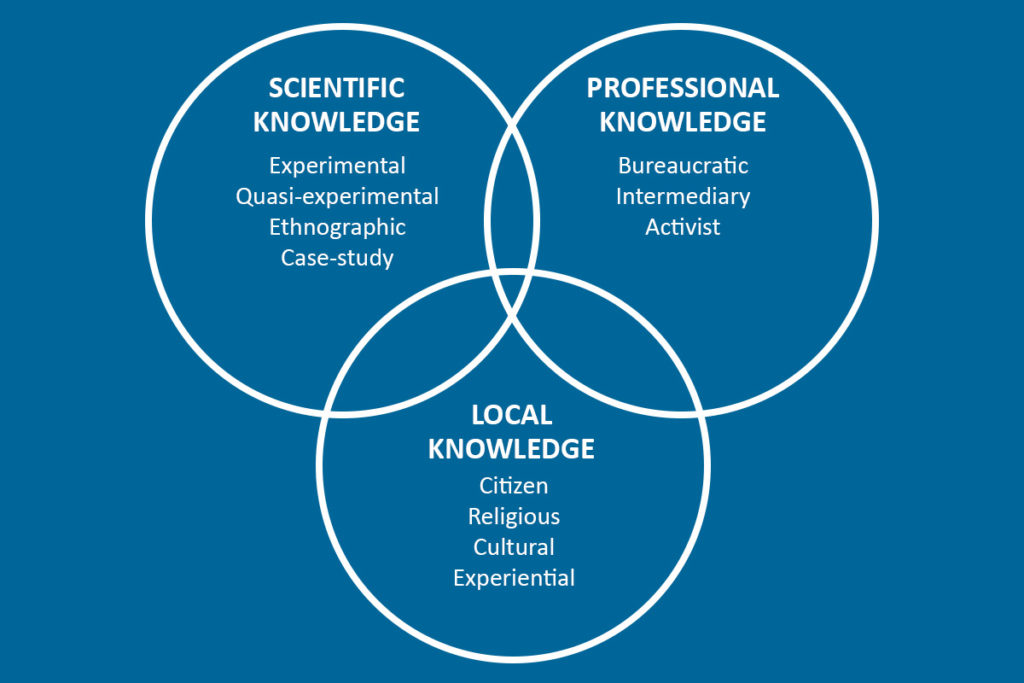

Based on our analysis, we identified three types of knowledge that contribute to the creation of evidence to inform policy design in development work:

- Local knowledge: Knowledge that people in a community or an organization have accumulated over time–often generations–based on their worldviews and lived experiences in societies and in the environment.

- Professional knowledge: Knowledge that generates evidence is professional knowledge, what Jones et al. call practice-informed knowledge. Professional knowledge may be held by anyone, but in the policymaking context, it is most often held by bureaucrats, think tanks, and civil society advocacy or interest groups. The strength of professional knowledge is process knowledge, how to get things done within certain circumstances and limitations, or the art of the possible.

- Scientific knowledge: Knowledge that is obtained through scientific standards and norms within the scientific community, where the solidity of scientific achievements is a matter of alignment between data, arguments, interests, dominant values and circumstances.

I now turn to highlight our findings about how local knowledge contributed to improved policy effectiveness in the selected four case studies:

Relationship-based influence: In the case of the community profit sharing project in Aceh, communities utilized local knowledge to mobilize personal networks to approach policymakers to build trust as a pre-requisite to following the procedural/legal process to formalize policy changes. With this approach, the community’s local knowledge was shared with government actors through the advocacy NGO Yayasan Kesejahteraan Umat (YKU). YKU engaged with various stakeholders and important actors with information at multiple stages and levels of the project, including village leaders, religious figures, and agriculture educators, all of whom were important actors in generating and communicating local knowledge.

Local knowledge as an electoral asset: In the case of the community-based water resource management project in East Nusa Tenggara Province, local NGO Pikul shared input from the local community concerning the installation of water systems. A sub-national system was initially proposed, but a localized water management system won the day because it was accepted by many people who represented a significant electoral asset.

Community participation and co-creation: In the case of the climate change adaptation project in West Java and West Nusa Tenggara Province, NGOs working on behalf of farmers and scientific researchers worked with the communities facing the most serious environmental risks to challenge the distinctions between experts and lay people. For example, the Centre for Anthropological Studies, University of Indonesia (PUSKA Antropologi UI) worked to improve farmers’ traditional and more recently empirical knowledge to address climate change, ensuring that scientific and local knowledge complement each other in forecasting climate patterns.

Another mechanism used by intermediaries representing local communities to influence policymaking was to provide a “reality check” or feedback to policymakers about the impacts of existing policies. One of the approaches we observed under this reality check mechanism was to provide empirical evidence about “distributive justice.” In the case of the community-based health care financing project in Southeast Sulawesi, data and experiences from community members on the use of the government health insurance scheme (BPJS-Kesehatan) was collected. The investigators then organized a seminar with stakeholders to present the community perspective on BPJS-Kesehatan implementation. The seminar provided empirical evidence about the limitations and challenges of the BPJS-Kesehatan policy and how the community-based system could complement the formal system. This activity encouraged the local government to bridge the gap between the calculation of BPJS health fees and the real needs of the people by providing a complementary service to local health insurance.

Implications and Takeaways

That is, each form of knowledge adds unique value to the processes of decision-making and implementation and how we define success, learn, adapt and improve. Indeed, when all types of knowledge are treated equally, we create spaces for fuller learning about the “creation story” underpinning the policies in question. Crucially, beyond than just contributing to policy formulation, local knowledge plays a central role in successful policy implementation, in part because it is more grounded in the context of the communities impacted most by these policies.

The key lesson is that as development practitioners we should not privilege one type of knowledge over another, but make sure we are proactively incorporating the right balance of all knowledge types. Striking this balance between the types of knowledge will depend on the specifics of a given context, which invites further research and verification of our findings, especially as the conversations surrounding decolonizing global health, localization, and locally led development gain more attention.

Photo credit: Adapted from Local Knowledge Matters, Policy Press.