By: Robyn Dayton and Betty Alvarez

Click here for a Spanish version of this post.

In the Dominican Republic, one of the questions most faced by public health officials, law enforcement and civil society is how to address gender-based violence (GBV) – particularly intimate partner violence (IPV) and violence against key populations (men who have sex with men, transgender women, sex workers) and people living with HIV.

To respond to the urgent need for GBV response and address the concentrated epidemic of HIV in the country, the USAID and PEPFAR-supported LINKAGES project supported the Center for Promotion and Human Solidarity (CEPROSH), operating in Puerto Plata, to integrate GBV services into their existing HIV program beginning in late 2016. The integration effort not only created a unique opportunity to meet pressing needs, it also provided us the chance to evaluate the approach and help build the evidence base for effective integrated strategies to address GBV and HIV. For the program implementers, the evaluation revealed how they perceived their new responsibilities and provided information for intervention improvement and data to support local advocacy and build buy-in. We describe our evaluation and results in this post.

The intervention

The GBV technical working group led the development of a “route of services” for all survivors of violence, trainings and technical assistance to organizations that were part of the route of services (to ensure quality and stigma-free services for all), and met regularly to plan demand generation activities. These activities included outreach events to key population members and community leaders to sensitize individuals on their right to live free of violence and the services available to survivors. CEPROSH also trained peer educators to accompany survivors of violence to services and offered therapy and support groups, from a team of social workers, to anyone who reported violence.

Methods

Our team of LINKAGES staff evaluated CEPROSH’s approach for integrating GBV services into their existing HIV program using qualitative and quantitative methods. The qualitative data collection consisted of 23 semi-structured interviews with GBV service providers and service users in July 2017. We asked service providers (n = 16) to describe their experiences implementing the program and the changes they had seen among service users. We asked service users (n = 7), representing key population members and people living with HIV, about the impact of the intervention on their lives.

Our team used field notes and audio recordings to collect the interview data. After translating the field notes into English, we coded and analyzed the data in Microsoft Excel. We established inter-coder reliability using a two-part process. A researcher coded the data that was then verified by others on the team. Then staff reviewed the matrix and reduced and organized the data into themes.

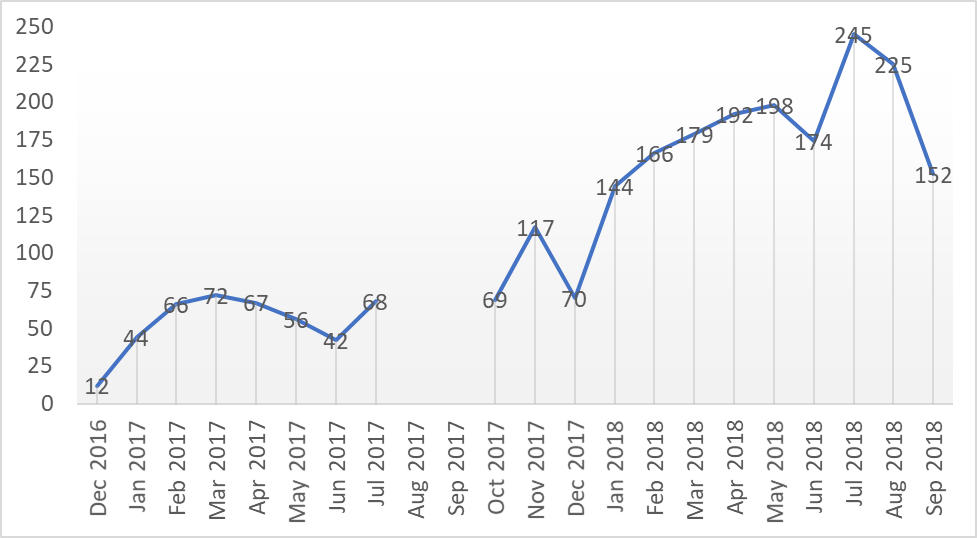

For the quantitative data, as part of its routine data collection, CEPROSH recorded de-identified data on the individuals who reported GBV. Our staff documented experiences of violence – based on categories described in key population guidance – from November 2016 to August 2017 and from January to September 2018. Data collected included the survivor’s sex assigned at birth, gender identity, key population, the type of services received (e.g., HIV testing, post-exposure prophylaxis) and HIV test results. Our team entered all relevant data into Excel and analyzed it with descriptive statistics.

Results

Our findings also show improvements in services coupled with demand generation activities to encourage disclosure of violence among all the populations served; CEPROSH linked any individual to GBV care that disclosed violence. Over the life of the intervention, 2,358 individuals disclosed violence to CEPROSH. This included 71 transgender women and two transgender men; 559 men who have sex with men; 938 female sex workers; 296 individuals living with HIV but not members of any key population group; and 492 members of the general population. Public sector post-GBV response service providers also saw an increase in the number of survivors seeking support and improvements in their outcomes.

A peer educator described the result this way, “I have two clients that had abandoned their treatment because of violence situations, and we were able to bring them back to treatment thanks to the GBV services. I think that many dropout cases are because of violence; they don’t feel important, they don’t feel support and they think it is not worth living.” – NGO-based social services provider 09

Implications

For those implementing the integrated services, the evaluation assured them that after years of seeing violence worsen in the country, they were on the right track and addressing violence in a way that could also improve HIV-related outcomes. As a result, buy-in from service providers further increased, and the multi-sectoral GBV response team that CEPROSH organized to plan and govern the intervention has continued to meet and support joint GBV response activities even once funding ended.

Having a model that works to synergistically address both epidemics could efficiently benefit a huge portion of the global population as 1 in 3 women globally have experienced GBV (WHO, 2017) and 37 million people are living with HIV (UNAIDS, 2018). A more rigorous research project should build from this initial program evaluation in Puerto Plata. Many anecdotal reports from service providers, such as reports from the District Attorney’s Office that recidivism has reduced, should also be rigorously tested to build buy-in across sectors, not only in health. HIV and GBV are both pressing issues all over the world; initial efforts, such as this one, can contribute to positive change.

Photo credit: FHI 360