By: Kayla Stankevitz and Definate Nhamo

For years, discussions about how best to reach HIV epidemic control have revolved around whether to focus on scale-up of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for people living with HIV or to provide more resources for prevention. “Test-and-treat”, a strategy in which HIV testing is intensified to diagnose and link people living with HIV to treatment, has been a widely accepted approach since its introduction in 2009. However, since that time the global health community has made great strides in HIV prevention with the introduction of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and other prevention technologies. As countries intensify HIV testing efforts in a bid to “test-and-treat” there are increasingly greater numbers of people that test negative for HIV identified in the process. Some of these people are at high risk of HIV infection and may be good candidates for HIV prevention services like PrEP.

Context and methods

USAID funded the OPTIONS consortium project to expedite access to HIV prevention products for women. The project worked across Africa, but primarily in Kenya, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Pangaea Zimbabwe AIDS Trust and FHI 360, in consultation with the Ministry of Health and Child Care and USAID in Zimbabwe, designed an intervention to explore the feasibility of using a test-and-prevent approach to intentionally link people that test negative for HIV to PrEP services.

Our team reviewed test-and-treat literature to determine which existing strategies could be used to effectively link people that test negative for HIV to prevention services, with a focus on oral PrEP. We aimed to identify a package of low-cost, effective interventions that aligned with the national HIV testing guidelines. We had to acknowledge important differences in ART and PrEP provision, mainly, that while every person testing positive for HIV is a good candidate for ART, not every person testing negative for HIV is a good candidate for PrEP.

We implemented our intervention in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, at six public sites, including one central hospital. Bulawayo is Zimbabwe’s second largest city with an HIV prevalence of 17.9%, which is higher than the national prevalence of 14.6%. It is an industrial town with its HIV prevalence driven by key populations, including adolescent girls and young women.

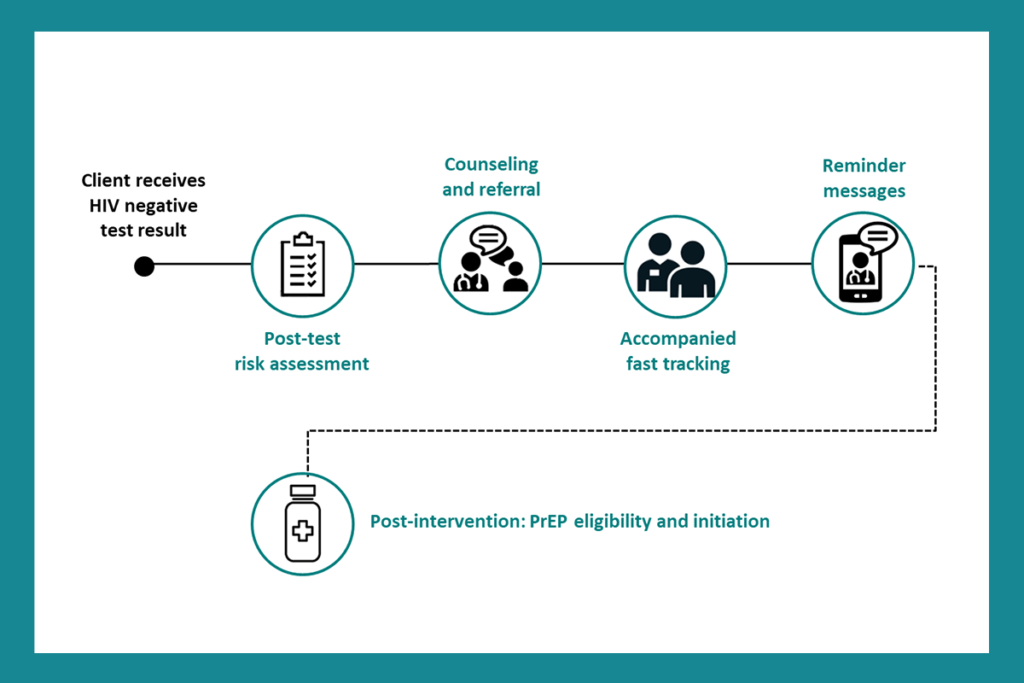

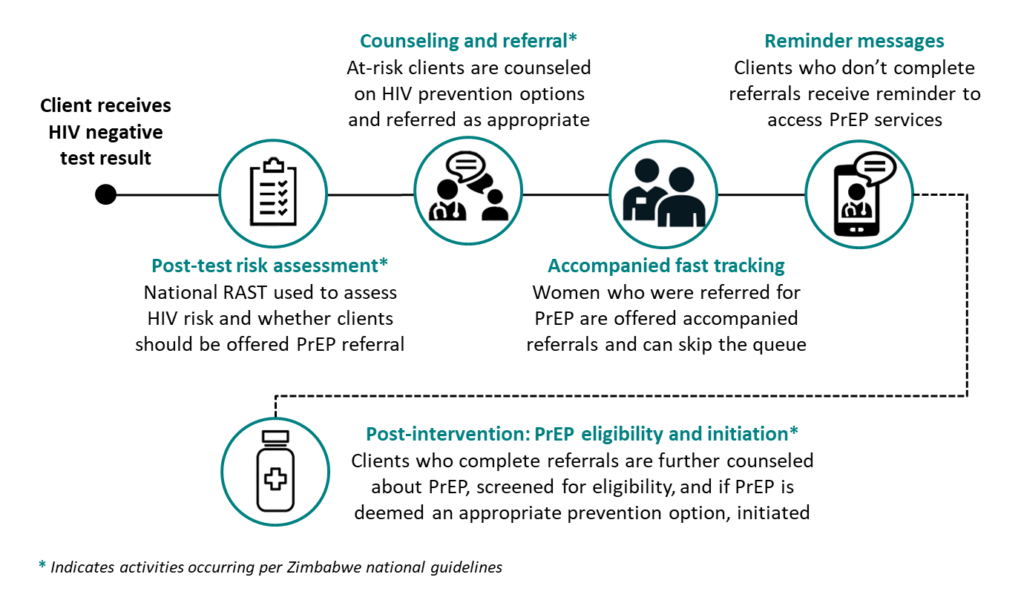

Our final test-and-prevent intervention contained four main components, as shown in Figure 1. Note that Zimbabwe national guidelines already required some of the intervention components but they were not currently occurring in the study sites. The first component asked providers to go through a Risk Assessment Screening Tool (RAST) with people that test negative for HIV, to assess for HIV risk and PrEP eligibility. The second looked at the need to counsel people deemed eligible for PrEP and proactively provide referrals for HIV prevention services. The third asked providers to offer accompanied referrals to people deemed eligible for PrEP in a bid to fast-tract and minimize procrastination of taking up HIV prevention options available. And fourth, we followed up via SMS after two weeks with people referred for PrEP services but that had delayed service uptake to remind them to come in for PrEP.

We conducted qualitative interviews with health care providers, facility managers and people that tested negative for HIV to get a better understanding of what worked well and what could be improved. We analyzed qualitative data using a structured codebook in NVivo.

Findings and implications

We conducted our study between November 2019 and February 2020, during a time when many real-world factors influenced delivery of health care services in Bulawayo. Supply shortages and distribution issues led to delays in PrEP rollout in study sites. We had planned to conduct the study once PrEP was already delivered to sites and once clinic staff were used to the added responsibilities. However, delays in rollout coupled with the need to complete this study before the OPTIONS project closed, led us to implement the intervention in conjunction with PrEP rollout. Furthermore, study sites experienced staff shortages throughout the study period. Nurses in Bulawayo were on strike to demand higher salaries. These challenges highlighted both the importance of doing research in real-world settings, and the importance of qualitative data collection to capture the nuances of intervention versus environment (when a control group is not available).

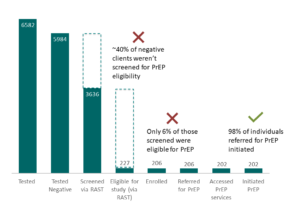

While we concluded that accompanied referrals and reminders could effectively enable people referred to PrEP to access PrEP services, we found important barriers to referral earlier in the test-and-prevent cascade. When asked about gaps in screening, health care providers reported not conducting HIV risk assessments with all people that test negative for HIV – instead providers made judgments on who to administer risk assessments to based on presumed risk (such as the HIV-negative partner in a serodifferent relationship or people identifying as members of a key population group). Further, health care providers expressed concern over the sensitivity of the risk assessment tool questions. Providers felt that some of the questions evoked some level of discomfort due to the questions asking about a person’s sexual activity. With this, some providers resolved to utilizing their counseling skills and their own judgment on risk as opposed to using the risk assessment tool.

We also identified some overlap between risk assessment tools for HIV testing eligibility and PrEP eligibility. During the same period our study was conducted, in a bid to maximize resources, PEPFAR introduced an adult screening tool that was to be used before HIV testing to try and target HIV testing to those who need it the most rather than test everyone coming to a health facility. The RAST, per national guidelines, was meant to be used after HIV testing with those who tested negative to determine PrEP eligibility. Providers felt the adult screening tool and the RAST duplicated efforts in determining individual risk. Surprisingly, few people tested for HIV were deemed eligible for PrEP based on the RAST, suggesting a disconnect between the two tools. We recommend further examination of the tools to ensure people are not unnecessarily screened out for PrEP.

Overall, we found our intervention to be well accepted, with providers highlighting the increased workload that HIV prevention products like PrEP causes.

While we hypothesized the challenges in a test-and-prevent approach to primarily be in getting people that test negative for HIV referred to PrEP to complete those referrals (or the “linkage” to prevention), the real gaps were in identifying good candidates in the first place. The Ministry of Health and Child Care received our findings well and is in the process of synchronizing the adult screening tool and the risk assessment tool (RAST) as both tools are aimed at identifying people at risk of HIV and ultimately linking them to treatment or HIV prevention services.

Photo credit: Kayla Stankevitz/FHI 360