This blog post is the second in a two-part series on contraceptive research. This post originally appeared on the Contraceptive Technology Innovation (CTI) Exchange.

Contraceptive clinical trials routinely collect vast amounts of data, but what new data can we collect about method acceptability during this research stage? If a method has reached the clinical trial phase, we’d hope formative acceptability research was already conducted to inform its development and to determine if a potential market exists. At this point in the game, few changes can be made to a method based on acceptability findings… so what’s left to learn?

First, clinics chosen for trials are generally high-quality, well-resourced facilities, often located at or associated with research institutions. This likely differs from smaller or resource-limited clinics, and from standard clinical practice more generally, where staff specifically dedicated to the clinical trial are not present.

Second, clinical trial protocols detail precise procedures for counseling participants about the drug or device under investigation and include follow-up visits and clinical tests. In contrast, counseling in a standard clinic setting may be limited, with follow-up visits and testing perhaps happening only if clinically indicated.

Within the contraceptive clinical trial context, how is product acceptability measured? We know that researchers routinely collect some narrowly-framed acceptability data, often using method continuation rates as an indicator of product acceptability. Given the highly-controlled and usually incentivized context of a clinical trial, continued use is a pretty low bar. Beyond that, researchers may collect data on trial participants’ attitudes about the method by asking them: (a) to rate their level of satisfaction on a Likert scale, (b) if they would choose to continue using the method after the trial, and/or (c) if they would recommend the method to a friend.

The problem is answers can be overstated due to social desirability bias, and people are generally bad at predicting their future behavior. So how can we improve upon these currently used measures and incorporate some aspects of the “real world” experience?

We can ask trial participants about benefits and difficulties they faced while using the method and how these issues impact their lives. This is important because some side effects experienced by users may not be clinically relevant to the safety or efficacy of the contraceptive but very pertinent to acceptability and a user’s everyday life. We can ask participants about counseling information. How well did they understand the information? Based on their experience, what information was helpful, and what information was missing?

Granted, some of this user experience information is difficult to measure within the standard confines of a clinical trial. Incorporating more behavioral and social science methods into the research approach would be a good start. For clinical researchers who find this kind of research a foreign concept, perhaps they could gain insights from comparable methodology employed by consumer product market researchers or by approaches used during earlier stages of product development as discussed in previous blogs in this series.

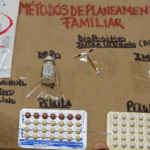

Photo credit: Medical image created by Ijeab – Freepik.com