A group of advocates met outside San Francisco in 2007 to pen eight principles of open government data with the intent of initiating a new era of democratic innovation and economic opportunity. In the decade since, governments are slowly opening up their data sets as a public resource, and even adopting other open data as their official data. More than 15 national governments (and 25 local governments) have now adopted the principles of open data and its potential to foster greater transparency, empower citizens, combat corruption, and generally enhance governance. Despite the gradual movement towards open government data, very little is actually known about its impact – what, where, how and under what conditions does open data work?

Our approach and methodology

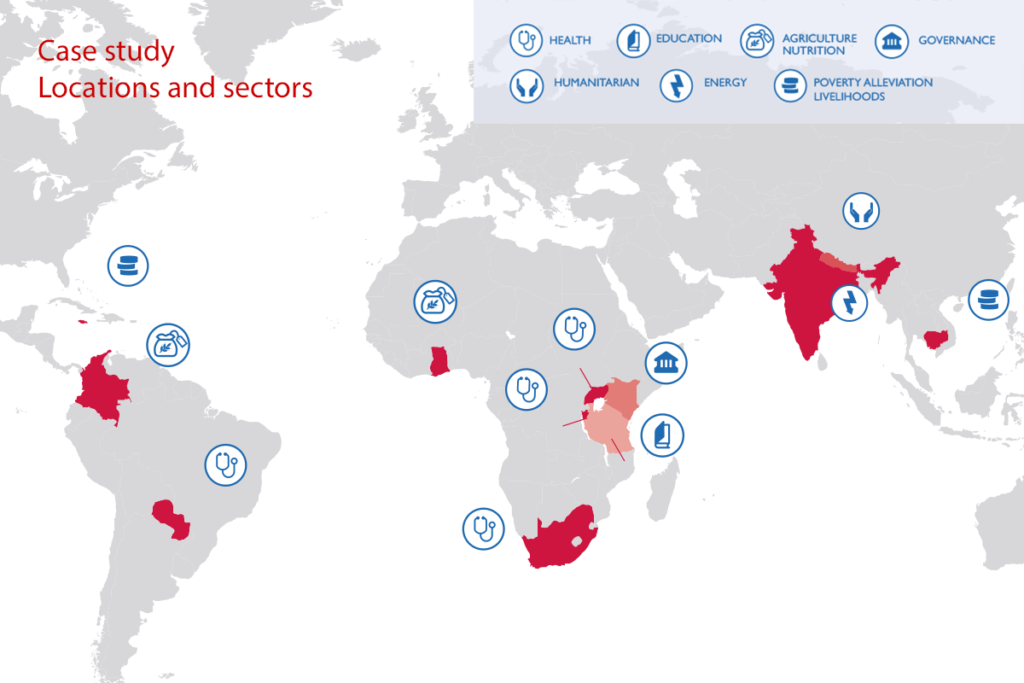

The research started with a desk review of existing gray and peer-reviewed literature to identify any prevailing evidence of impact sparked by open government data interventions. We identified dozens of active open government data projects around the developing world. Based on geographic diversity, sector inclusion, and availability of existing evidence, we selected 12 case studies for inclusion in a deep-dive study.

The selection of case studies was followed by a documents review, consultations, and qualitative interviews with a wide variety of project stakeholders over the course of three months. A Research Advisory Committee, composed of open data experts, provided technical oversight, guidance, and valuable inputs throughout the research.

Selected case studies findings

Here are three of the salient and cherry-picked examples from the report that suggest positive outcomes.

Burundi case study

Burundi is one of the world’s most resource-constrained countries and has consistently poor health outcomes. As part of its effort to improve health outcomes and health system functioning, Burundi was one of the first African countries to introduce results based financing (RBF) in the health sector. RBF is an instrument that links development financing with pre-determined results. Payment is made only when the agreed-upon results are shown to have been achieved.

As described in the Burundi case study, health service providers in Burundi generate qualitative and quantitative data relating to services provided. These providers use Open RBF, a web-based, open source platform for managing data. The portal contains both private and public data interfaces geared towards different intended audiences.

The private interfaces store project-level details like project progress and performance indicators. Access rights limit private users to district, province and national level data. Funding organizations simultaneously use the data for oversight purposes. The Ministry of Health uses the data to track different health-related indicators and progress made by each health facility or catchment area; medical practitioners and policymakers also use the data for programmatic objectives. The public interfaces present data in a different format that allows data to be aggregated by district, province and relevant health performance indicators such as vaccination rates, status of antenatal care visits, or rate of delivery at health facilities, etc. These public interfaces are mostly accessed by citizens in the form of open data.

South Africa case study

South Africa is a country where medicine prices are regulated by the government, but all buyers and sellers have access. This market creates affordable alternatives by having both generic and branded medicines available to patients. Although generic medicines are comparatively cheaper for patients, doctors in South Africa do not always prescribe them. In some cases, the doctors may not be aware of equivalent options, in others they might rely on pharmacists to suggest an option based on available stock and agreements with distributors.

By law, the South Africa Department of Health (DOH) is required to make medicine pricing transparent. Therefore, DOH openly publishes such data on its Medicine Price Registry website. As described in the South Africa case study, a non-profit organization called Code for South Africa (Code4SA) used the data set from the DOH website to create the Medicine Price Registry Application (MPRApp) tool. This publicly available tool allows patients to search and compare medicine prices.

Although the Medicine Price Registry data was already open to the public, a typical user had to take several steps to download large and sophisticated Excel sheets. To compare prices also required technical skills to search and filter the data. Code4SA leveraged the open data to provide patients with an easy-to-use, searchable form. The resulting MPRApp tool compares the costs of doctor-prescribed medicines with those of other medicines containing the same ingredients. MPRApp utilizes a public database that contains products’ details, prices, formula ingredients and available dosages of all government-approved medicines. The tool intends to help patients verify prices, avoid overcharges by their pharmacies, and ensure cost-savings without compromising on efficacy.

There is anecdotal evidence that doctors in South Africa use the information provided by MPRApp to save their patients money. MPRApp currently relies on the personal commitment and skills of its developers to be updated regularly. The overall sustainability, continued use, and impact of the application remains uncertain unless long-term funding is secured. MPRApp has presumably impacted the lives of South Africans; this impact, however, is based on an extremely limited number of cases and under-analyzed web analytics (but we do know there are about 2,000 website visitors per month, and that most are repeat visitors). The opportunity for a formal large-scale survey measuring the awareness, use, and impact of MPRApp is ripe for implementation.

Colombia case study

Rice cultivation is a prime source of income and means of livelihood to smallholder farmers in Colombia. Compared to the previous decade, the yield of irrigated rice declined from 6 to 5 tons per hectare between 2007 and 2012 – eliminating previously achieved increases in production. Although the main cause of rice harvest reductions is not fully known, climate change is believed to be the prime suspect.

As described in the Colombia case study, the National Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies (IDEAM) regularly collects, processes and disseminates climate data as open climate data. The International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), a civil society organization, led a cross-sector partnership called the Aclímate Colombia Project that utilized a variety of data sources to assist farmers with understanding how to better navigate volatile weather patterns.

Colombian rice farmers were already facing the effects of climate change in 2013 when the winner of the UN Big Data Climate Challenge, Fedearroz, gave a recommendation, “Don’t plant in this sowing season.” Based on existing research that the most planted rice is sensitive to climate change, Fedearroz’s recommendation allowed farmers to protect their yields with an estimated loss savings of $3.6 million. Although the warning to farmers was the result of research, the causal relationship to the financial estimation is calculated by Fedearroz and is not necessarily backed by hardcore evidence.

What is the path forward?

About a decade ago, the mHealth sphere was also thirsting for evidence and then thousands of papers were commissioned to create an evidence base of what works and what doesn’t and why. Mirroring this generation of evidence requires deliberate attention be given to open government data interventions. It’s a paradigm-shift away from thinking “if you build it, they will come” – not a strong strategy for accelerating adoption and impact – to a more organized and integrated approach of treating open data differently. Based on the research conducted, our team developed a theory of change and periodic table detailing enabling conditions and disabling factors to leverage the impact of open government data as a new untapped asset for human development.

Photo credit: FHI 360