The use of quality improvement approaches (known as “QI”) to improve health care service outcomes has spread rapidly in recent years. Although QI has contributed to the achievement of measurably significant results as diverse as decreasing maternal mortality from post-partum hemorrhage to increasing compliance with HIV standards of care, its evidence base remains questioned by researchers. The scientific community understandably wants rigorously designed evaluations, consistency in results measurement, proof of attribution of results to specific interventions, and generalizability of findings so that evaluation can help to elevate QI to the status of a “science”. However, evaluation of QI remains a challenge and not everyone agrees on the appropriate methodology to evaluate QI efforts.

In this post, we begin by reviewing a generic model of quality improvement and explore relevant evaluation questions for QI efforts. We then look at the arguments made by improvers and researchers for evaluation methods. We conclude by presenting an initial evaluation framework for QI developed at a recent international QI conference.

What is QI?

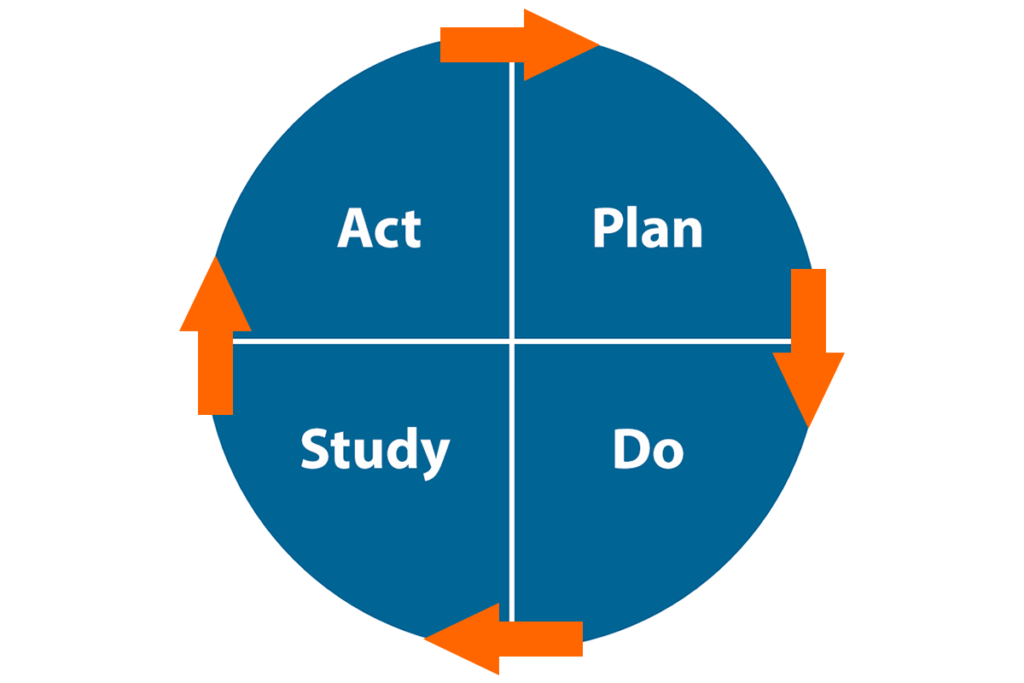

QI, as defined by the Health Resources and Services Administration, “consists of systematic and continuous actions that lead to measurable improvement in health care services and the health status of targeted patient groups”. FHI 360 uses a quality improvement model adapted from The Improvement Guide and shown in Figure 1. An important concept behind this model is the recognition that improvement happens by making changes in the system, but not every change is an improvement. To ensure that QI produces changes that yield improvements, we use the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle of learning and improvement to test changes before adopting them. The use of specific tools (run charts or control charts) to analyze variations in the performance of a system is an essential part of the model for improvement and provides the foundation for the correct interpretation of the relationship between changes and improvements.

How can we establish the evidence base for QI?

In recent years, several authors have published articles (such as Donald Berwick and Andrew Auerbach) that reflect opposing perspectives between “improvers” and “researchers” about the most appropriate methodologies to evaluate QI programs and generate evidence that QI “works”. For improvers, measurements of progress over time against explicit improvement objectives are sufficient to attribute results to the QI interventions (these are called “systems” changes) when nothing else is known to have contributed to these results and charts are interpreted following statistically-validated rules. That is, improvers argue that the results speak for themselves.

For some clinical researchers, however, only sacrosanct gold standard randomized controlled trials (RCTs) can speak to attribution. Researchers argue that the absence of a control group weakens the evidence on the true impact of QI. The truth is likely between these two opposite views, where improvers and researchers must work together to use the most appropriate evaluation methods to answer the questions that matter.

The right evaluation questions for QI

In thinking about evaluation questions for QI, we should first consider whether it is relevant to ask the big question, “does QI work?” Asking that is like asking whether medicine works, or public health works, or management works. QI is an approach, not a single intervention. When looking at the effectiveness of a general approach, the answer is invariably “it depends”, where what it depends on includes context and other specific factors affecting QI efforts. Examples of more useful questions are:

- Why did we achieve, or fail to achieve, improvements?

- Are the improvements due to changes that were implemented through a QI process?

- In which circumstances did a specific QI effort produce results superior to other approaches?

- What did all involved in the QI effort learn about the system they are trying to improve?

The evaluation of QI is broader than an effectiveness study of a distinct intervention, with the intent to generate learning through systematic documentation of QI inputs, processes and outputs and using both quantitative and qualitative research methods to fully analyze the data.

Why not RCTs?

Improvers argue (example here) that a randomized design is inappropriate to evaluate a QI effort. They provide examples of evaluations that point to flawed conclusions due to the rigidity of controlled designs that eliminate the very contextual factors that are necessary to explain variations in results across QI teams and between QI sites. These contextual factors contribute to the essential knowledge generated from a QI effort that enables us to answer the questions above. Controlled designs create an artificial and non-replicable environment that is contrary to the real world within which changes are introduced through QI. While they are appropriate to study the linear and mechanical causal relationships between a drug and its target, RCTs are simply unfit to study the effects of a social change introduced in a complex, unstable and non-linear living system.

We need to interpret results (or lack thereof) of QI efforts from the perspective of introducing changes to a complex adaptive system influenced by social and economic contexts. A QI process is no different from a behavior change intervention, except the focus is on how systems behave rather than on how individuals behave. To evaluate and learn from QI, we need more than just the measured changes but information on when, where and why improvement happened (or not). Scientific research methods that include both quantitative research and qualitative research will complement the work of the improvers and generate learning beyond the simple description of changes implemented.

How can we learn more about improvement?

To address the evaluation challenges of QI efforts, in July 2016, 61 of the world’s most respected health care improvers and research scientists met in Salzburg, Austria for a five-day interactive session entitled “Better Health Care: How Do We Learn about Improvement?” organized by the Salzburg Global Seminar. They were tasked with answering the question “Are the results being obtained by QI efforts attributable to the changes being made?” While the discussions at Salzburg were initially framed by the “improver/evaluator” dichotomy, by the end of the session participants could identify the benefits of a model where evaluation was a consideration beginning at the design stage of a QI program. A framework for learning about improvement (see Figure 2; source here) was developed to guide the design of the improvement efforts and the integration of its evaluation. In other words, the improvement effort is designed with its evaluation in mind. More work remains to operationalize the evaluation framework, including identifying appropriate methods to rigorously and appropriately capture the impact of QI without compromising the iterative, adaptive nature of improvement.

This is exciting work in progress, with QI experts leading the way by engaging researchers on the path to addressing the evaluation challenge and identifying appropriate methodologies to “crack open the black box of QI”.

FHI 360 is part of this global effort through its participation in the Salzburg seminar and the follow-up activities, the development of the evaluation framework, its use in evaluating QI interventions related to the Zika epidemic in Latin America (link here) and other efforts to document QI work across many programs.

Stay tuned!

Photo credit: FHI 360