I’ve always been interested in understanding the causes of food insecurity (and even more so since my graduate studies), mainly because these drivers are often cross-cutting and involve multiple fields of study. I get even more excited reading about solutions to food insecurity, as they require innovative thinking across diverse fields.

Researchers from the University of South Carolina, International Food Policy Research Institute, FHI 360, BRAC, and Save the Children recently published a study of one such innovative solution in Bangladesh. They found that by integrating nutrition into existing antenatal care, household food insecurity was reduced among pregnant and recently delivered mothers.

In this post, I summarize the findings of this study, what makes them interesting, and what I’m still left wondering about.

What is the intervention and what did they find?

In the article, “Nutrition interventions integrated into an existing maternal, neonatal, and child health (MNCH) program reduce food insecurity among recently delivered and pregnant women in Bangladesh” (gasps for air) Frongillo, et al. examine the impact of an integrated nutrition-MNCH package (compared to the standard MNCH package) on household food security among pregnant and recently delivered women using a cluster-randomized, non-blinded design (gasps for air, again). The authors hypothesize that an integrated approach to improving nutrition knowledge and altering resource allocation choices will increase the purchase and availability of quality food in the household. All these things, in turn, will increase household food security.

The researchers randomly assigned 20 subdistricts in Bangladesh to either the intervention package (n = 10) or the standard package (n = 10). The team enrolled 300 pregnant women and 1,000 recently delivered women in each study arm, and then administered household surveys, which included the standardized FANTA/USAID Household Food Insecurity Access Scale questionnaire, at baseline (June–August 2015) and endline (June–August 2016).

The intervention package had two main components. The researchers implemented the first component during monthly antenatal visits. Shasthya Kormi (frontline workers) and Shasthya Sebika (health volunteers) encouraged healthy diet plans while also engaging husbands and other family members to support mothers in their diet by increasing the availability of food in the household.

The second component mobilized community members through forums and interactive video shows. The forums specifically targeted husbands, emphasizing the importance of nutritious diets for their wives during pregnancy and the postpartum period. These forums also encouraged husbands to purchase diversified foods, ensure that their wives followed the recommended diet and took micronutrient supplements. The researchers disseminated the video shows to the broader community and covered multiple nutrition topics. One theme conveyed in these video shows emphasized how important it was for pregnant women to have diverse and nutritious foods available, even if that meant prioritizing food over other needs or wants.

The standard MNCH package, as you might have guessed, didn’t have a nutrition focus. This package provided standard antenatal care, required patients to pay for micronutrient supplements, and didn’t have a community mobilization component.

So, what did the researchers find?

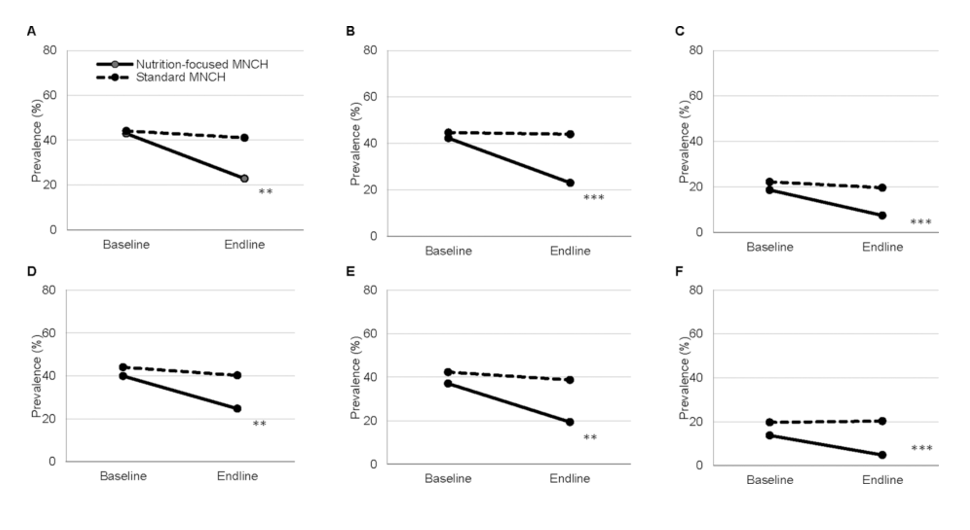

At the beginning of the intervention, the prevalence of food insecurity was comparable between both groups, with almost half of the households experiencing food insecurity. A year later, at the end of the intervention, Frongillo, et al. found that there was a statistically significant difference in food insecurity between the two groups. The overall prevalence of food insecurity (i.e., mildly, moderately, and severely food insecure) for the intervention group was lower than that of the control group by 22.3 and 19.7 percentage points for recently delivered and pregnant women, respectively.

The figure below (pulled from the article) offers a great illustration of the baseline and endline differences. For example, in Panel B, you can see the percentage of recently delivered women who reported insufficient quality of food in the intervention group fell to 23 percent at endline, compared to 44 percent in the control group.

Household food insecurity among recently delivered women (RDW) and pregnant women (PW), by survey round (i.e., baseline in 2015 and endline in 2016) and intervention package (i.e., nutrition-focused and standard MNCH), for domains: (A) RDW-anxiety and uncertainty about the household food supply, (B) RDW-insufficient quality, (C) RDW-insufficient food intake, (D) PW-anxiety and uncertainty about the household food supply, (E) PW-insufficient quality, and (F) PW-insufficient food intake. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Source: J Nutr. 2019;149(1):159-166. doi:10.1093/jn/nxy249

Why is this interesting?

As outlined by the researchers, findings from this study are particularly interesting because they fill important gaps in the literature.

Frongillo, et al. show that food insecurity can be reduced by integrating nutrition programs into antenatal care. Evidence from a prior study suggests that food insecurity can be reduced through antenatal care, but is limited in its quasi-experimental design (Heberlain, et al., 2016). Additionally, while programs are beginning to integrate food security and nutrition interventions, few have integrated both food security and nutrition interventions into antenatal care.

The researchers also highlight how social and behavioral change can be an effective way to improve food security in a lower-middle income country. Findings from the United States show that nutrition education is associated with a decrease in food insecurity, with a dose-response relationship between number of lessons received and decreases in food security (Dollahite, et al., 2009). Frongillo, et al. expand on this evidence by showing the applicability of nutrition education in the context of Bangladesh.

For me, the most enticing aspects of the study are the cost-benefit and sustainability implications. This intervention, because it was integrated into an existing antenatal care system, didn’t require additional costly resources (e.g., providing food-in-kind, cash for food, or loans) or, what the researchers refer to as, “setting up new service-delivery channels”. The intervention simply changed behaviors by increasing knowledge and engaging communities; as a result, the intervention decreased household food insecurity.

What I’m left wondering about

While an interesting read, the study did leave me curious about a few things.

First, I found myself wondering about the other members of the households. It’s evident that the husbands, and perhaps even the mothers-in-law, played a large role in the intervention. I’d be interested to see the shifts (if any) in husband and mother-in-law perceptions, behaviors, and cultural norms (which the article does allude to in a sentence or two) around food and diet for mothers.

Second, I’m still curious about how the intervention improved household food security. Frongillo, et al. hypothesized that household decision-makers (husbands and mothers-in-law) would not only purchase more nutritious foods following improved knowledge from the intervention, but also choose nutritious foods over other household needs and wants. In other words, the researchers hypothesized that increased purchasing and altered resource allocation would mediate increased food security. While the researchers did find that a greater percentage of husbands in the intervention group reported being able to purchase healthy food compared to the control group, I’d like to know how these percentages compare to the baseline – and if it mediated the change in food security status. Furthermore, I’m curious about the trade-offs that these households faced and how the intervention encouraged households to prioritize food. If these households were to face economic and/or health shocks, would they still choose food over other needs?

Third, it would be interesting to see if there were differences in food insecurity status within the household. The authors provide an alternative explanation in the discussion for the impact of the intervention on food security, explaining that the increase in household food security could be inflated because the mothers were the ones who reported household food security status. Given the intervention focused on improved nutrition and availability of food for these women, the intervention might have benefitted them preferentially, rather than the entire household as a whole. However, evidence from a recent systematic review showed that in South Asian households, food allocation is often unequal and biased against women, especially youngest daughters-in-law (Harris-Fry, et al., 2017). Given this, I can’t help but wonder who’s really getting the food in the household. Would there be different results if questions were asked separately at the individual level and the household level (e.g., “Do you experience…” asked separately from “Do any members of your household experience…”)?

Frongillo, et al. show the positive impact of integrating nutrition interventions into existing antenatal care on household food security. While these findings do (partially) fulfill my hunger for innovative food insecurity solutions, I look forward to consuming more such evidence in the future.

Photo caption: Men sell fresh vegetables they grew at a village market in Baniajuri Union, Manikganj District, Bangladesh.

Photo credit: © 2004 Syed Ziaul Habib Roobon, Courtesy of Photoshare