Last month at our staff research seminar, we were pleased to host Elisabeth King and Cyrus Samii to introduce us to their recently published book, Diversity, Violence, and Recognition: How Recognizing Ethnic Identity Promotes Peace. King and Samii’s book is the result of a decade of reading, thinking, data analysis and writing about the big question of whether formal recognition of ethnic identity affects peace, and if so, in what direction? In this post, I summarize the main points of the book and share a few highlights for me.

Neither intuition is wrong. Instead, King and Samii’s answer – their theory of recognition – is more complex. In their theory the intuitive dynamics described above are called the mobilization effects and assuring effects of formal recognition, respectively. King and Samii add a “missing piece” to help us understand how these effects balance out in practice. This piece is the strategic position of the leadership regime with respect to the country’s ethnic divisions. They argue we need to also consider whether those in power are from a plurality ethnic group or a minority ethnic group. The assuring effects of formal ethnic recognition can benefit both kinds of leaders and further, should be good for peace. However, the mobilization effects of formal recognition create a threat for leaders from minority ethnic groups. These leaders face a risk when opposition groups with more people further coalesce around their ethnic identity. Thus, minority leaders face a “recognition dilemma”.

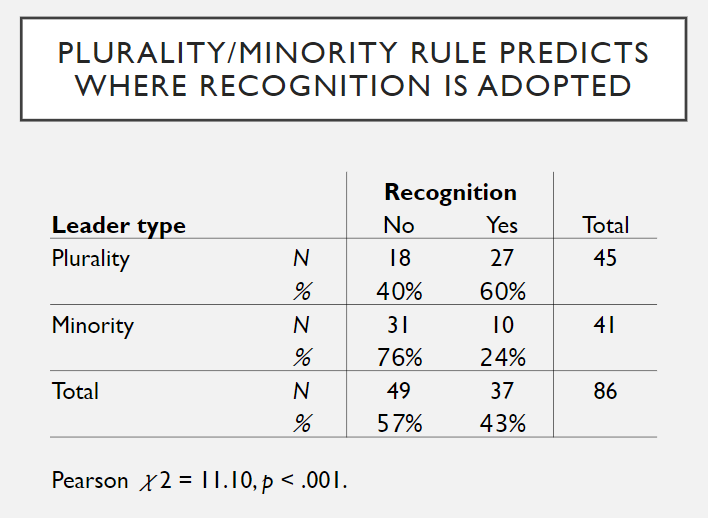

King and Samii’s theory generates two testable hypotheses. The first is that the strategic position of a leadership regime – whether the leadership is from a minority or plurality ethnic group – predicts the adoption choice of formal ethnic recognition. Minority leaders are less likely to adopt recognition and plurality leaders are more likely to adopt it. The second hypothesis is that these choices predict peace outcomes, such that we should expect “the most progress toward peace in regimes under plurality leadership that adopt recognition” (p. 34).

And here King and Samii really go to work. To test the first hypothesis, they constructed an impressive dataset comprising 86 “constitutional moments” across 57 countries that experienced conflict in the period 1990 to 2012. They coded variables for ethnic recognition and also for the ethnic composition of the countries and leadership. Of the 86 cases of constitutional moments, 43 percent had adoption of ethnic recognition. King and Samii provide a lot of analysis using these data, including exploring whether ethnic fractionalization is a moderator of these effects, but I’ll skip to the chase. They find that, “for plurality-led regimes, 60 percent of settlements or constitutions in conflict-affected contexts from 1990 to 2012 incorporated ethnic recognition. For minority-led regimes, the share is much less, only 24 percent” (p. 55). The table below is from their presentation at FHI 360.

To test the second hypothesis, whether the adoption of ethnic recognition predicts peace outcomes, they bring in additional data. They measure peace in three ways. They measure “negative peace” as the level of political violence using data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program. They measure “positive peace” using an indicator for democratic governance from the Varieties of Democracy project and GDP per capita. Using a difference-in-differences estimation approach, they estimate the effect of ethnic recognition on negative and positive peace for the minority rule cases and for the plurality rule cases. The results for negative peace are shown in the figure below from their presentation, which is taken from Figure 5.4 of the book (p. 77).

In these two charts, the dotted line is the estimated trend line for countries that do not adopt ethnic recognition. The solid line is the estimated difference in that trend for countries that do formally recognize ethnic groups. The shading shows the confidence interval around the estimation of the difference. The left side shows that in cases where the leadership comes from a minority ethnic group, adopting ethnic recognition does not make a difference. The solid line is a bit lower, but the confidence interval around it encompasses the estimates for non-recognition. This supports the theory that leaders from minority ethnic groups face a recognition dilemma. The opposition is both assured by the recognition and strengthened by the recognition such that recognition does not have a clear effect on peace. On the right side, we see for the cases of plurality rule, the estimated difference to the probability of violence from recognition is negative – it decreases the probability of violence – and it is statistically significant. This supports the theory that the assuring effects of recognition dominate when the leadership comes from plurality ethnic groups.

Those are the headline findings, but the analysis presented in the book is much richer with many useful insights. After reporting the quantitative data analysis, King and Samii present three in-depth country case studies: Burundi, Rwanda and Ethiopia. I focused on Ethiopia in my reading given the current events in that country. I won’t summarize the case studies here, but I do want to highlight one of King and Samii’s conclusions from those studies, that in reality “recognition strategies operate more as a continuum” (p. 163) than a binary outcome as the quantitative data analysis assumes.

The importance of the nuances was also apparent in the question-and-answer part of the seminar; my colleagues had a lot of “what about [fill in the blank country]?” questions as they pondered the application of King and Samii’s theory to the cases they’ve studied. The seminar happened in June 2020, so I and some of my U.S. colleagues also wondered whether any of this can apply to the conflict caused by racism in our own country. I posed that question to Cyrus in an email, and he responded that he thinks yes. He pointed me to this thread about affirmative action and quotas where he shares some of his thoughts. I agree, and as I continue to think through the theory and the analysis in the book, it is enriching my thinking about reparations.

For sure, this book is not one of those non-fiction books that “reads like fiction”. However, reading it did not feel like a purely academic endeavor. King and Samii know the histories of the countries they cover, so I learned much more about these countries from this book than just how they fit into King and Samii’s theory and evidence. They also provide a rich review of the corpus of academic thought on their topic, primarily from the field of political science. The plethora of references can make the prose a bit clunky but means that the reader learns from many specialists on this topic.

You can read Elisabeth and Cyrus’s own blog post about the book here.

Photo credits: Mockup psd created by Ydlabs – Freepik.com, Background image created by Creativeart – Freepik.com, Basic Books