Where medical barriers are concerned, these can include non-medically necessary policies or practices, such as requiring direct observation of menstruation through checking a soiled menstrual pad during the visit to rule out pregnancy, lab tests, or vaccinations. Clients may also face barriers due to a lack of information on how family planning methods work or stockouts of supplies at their area facilities.

Although the barriers above have been the subject of many studies, here and here, one additional barrier warrants examination: the role of provider bias in causing turnaway of clients seeking family planning. In this blog post, I highlight research conducted with my co-authors to better understand the role of family planning providers in turnaway and how to prevent it based on a study implemented in Malawi, which was recently published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, here.

Background

Family Planning in Malawi

After having decided that family planning is indeed the right decision for them, women in Malawi must often expend considerable time, financial resources, and effort to visit public family planning facilities. Starting a new method can take the better part of a day, including travel times, attending a group counseling session, waiting to see a provider, and finally either having a method inserted or obtaining a method from a pharmacy, which may not be located at the health facility where services are provided. If a woman is trying to conceal her use of family planning, she may decide to travel to a facility a bit further from her home community, thus increasing the amount of time and money expended.

After coming as far as making the decision to use family planning and getting to the facility, imagine the disappointment and frustration of being turned away without a method. Yet this is what happens all too often to many women and adolescent girls in Malawi. In related research conducted in three districts of Malawi, we found that 15 percent of women seeking family planning were turned away.

Role of Providers in Turnaway

Context and Methods

The data were collected as part of a larger study, in which data collectors spoke with clients exiting from family planning service areas to determine the proportion of clients turned away, as well as the reason for turnaway. To better understand the nuances behind turnaway, we also conducted surveys with 57 family planning providers and in-depth interviews with eight. It was important for us to hear directly from providers what went into their decisions to turn women away without a method.

Findings

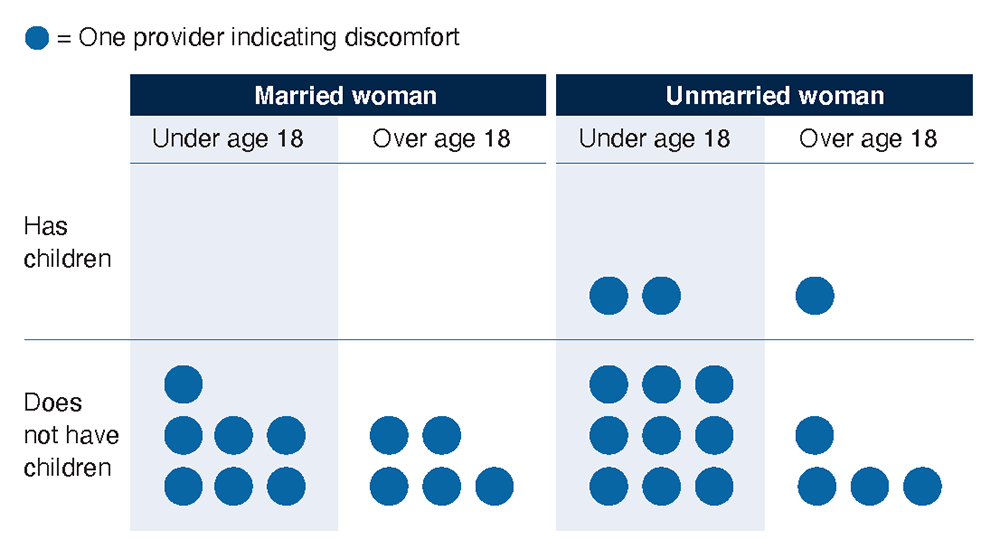

We also asked providers about their level of comfort providing family planning to clients both above and under the age of 18 years old, married, unmarried, and those with children and without. While few providers expressed discomfort with any of these groups, those who did were most uncomfortable with nulliparous clients. We were able to explore this further in the in-depth interviews, where providers explained that while they were aware from their training that family planning use would not impact future fertility, they could not help but worry that it would.

Figure 1: Providers that responded they were uncomfortable providing family planning services to each type of client. (Graphic by Sue-Lyn Erbeck, 2021)

Providers also worried about adolescent girls seeking family planning services. They worried that if adolescent girls were found out to be using these services in their communities, they would face verbal abuse, such as being called prostitutes. They also worried that family planning would enable girls to start or continue sexual relationships, and consequently would lose focus on their studies and not finish school.

One of the most commonly cited reasons for turnaway by clients surveyed in the larger study was that they were not able to show they were not pregnant. As pregnancy tests tend to be in short supply at facilities, providers often ask women to come to the facility when they have their periods—an obvious inconvenience for women. Through the in-depth interviews, providers were able to better explain to us why they required this, given that initiating most modern methods, except for IUDs, will not negatively impact a pregnancy. According to providers, many people believe that common family planning methods such as oral contraceptive pills, injectables, and implants will cause abortions. Additionally, they worried that women were seeking such services as a method of abortion, which is illegal in Malawi. Moreover, in the event women were pregnant before initiating family planning, they worried people would lose faith in modern methods, blaming their pregnancy on family planning failure, rather than recognizing the pregnancy occurred before service initiation.

Implications

Public health officials can support providers by providing training on all methods and on how to effectively rule out pregnancy before a missed period or when clients are not menstruating. They can also work to eliminate stockouts in methods and supplies, including pregnancy tests, and ensure there are adequate exam rooms to accommodate the full client load. Additionally, they can support education of the community on how contraceptive methods work, as well as dispelling common myths and encouraging more acceptance of the use of family planning, particularly for adolescent girls.

Photo credit: Daria Golubeva/Getty Images